Even as the rollout of vaccines all over the world brings a glimmer of hope that the current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic may end in the near future, new variants continue to emerge, some with the potential to escape vaccine-induced or therapeutic antibodies. Now, a new preprint research paper published on the bioRxiv* server describes a new American variant that may have become the dominant strain in the USA.

New regional variants arise over the course of a pandemic in part due to lockdowns, which restrict the population movement over a period of time. Another factor is the occurrence of multiple mutations at the same time. Epidemiologic surveillance of an infectious outbreak may involve genomic sequencing, which can allow new variants to be identified early in the course of the disease.

This method allowed the detection of a new severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variant, which arose early last year, but has now become very common in the USA. Called 20C-US by the researchers in the current study, it is part of the B.1.2 lineage.

*Important notice: bioRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: bioRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

Finding the new variant

The first isolation of this variant was towards the end of May 2020. Early on, it showed the presence of five mutations, which led to five changes in amino acid sequence. The affected genes are involved in virion maturation and release, viral protein processing, conservation of the RNA genome, and translation of viral proteins. It later acquired a pair of new mutations. One of these is the Q677H mutation in the spike protein adjacent to the spike cleavage site.

The researchers sequenced viral samples from Illinois and traced the emergence of a dominant strain within the 20C clade. The five defining mutations were then identified, namely, N1653D and R2613C in ORF (open reading frame) 1b, G172V in ORF3a, and P67S and P199L in the nucleocapsid (N) gene. The N gene mutation simultaneously introduced a stop codon mutation into ORF14.

Random samples were then sequenced from the national pool, showing that this variant made up a large proportion of genomes for most U.S. states, increasing over time, especially since July 2020. In the two months of November and December 2020, this strain makes up half of all sequenced isolates from the U.S.. However, it makes up only a minute proportion of sequences from other countries, including those as near the U.S. as Mexico and as far away as Australia and Poland.

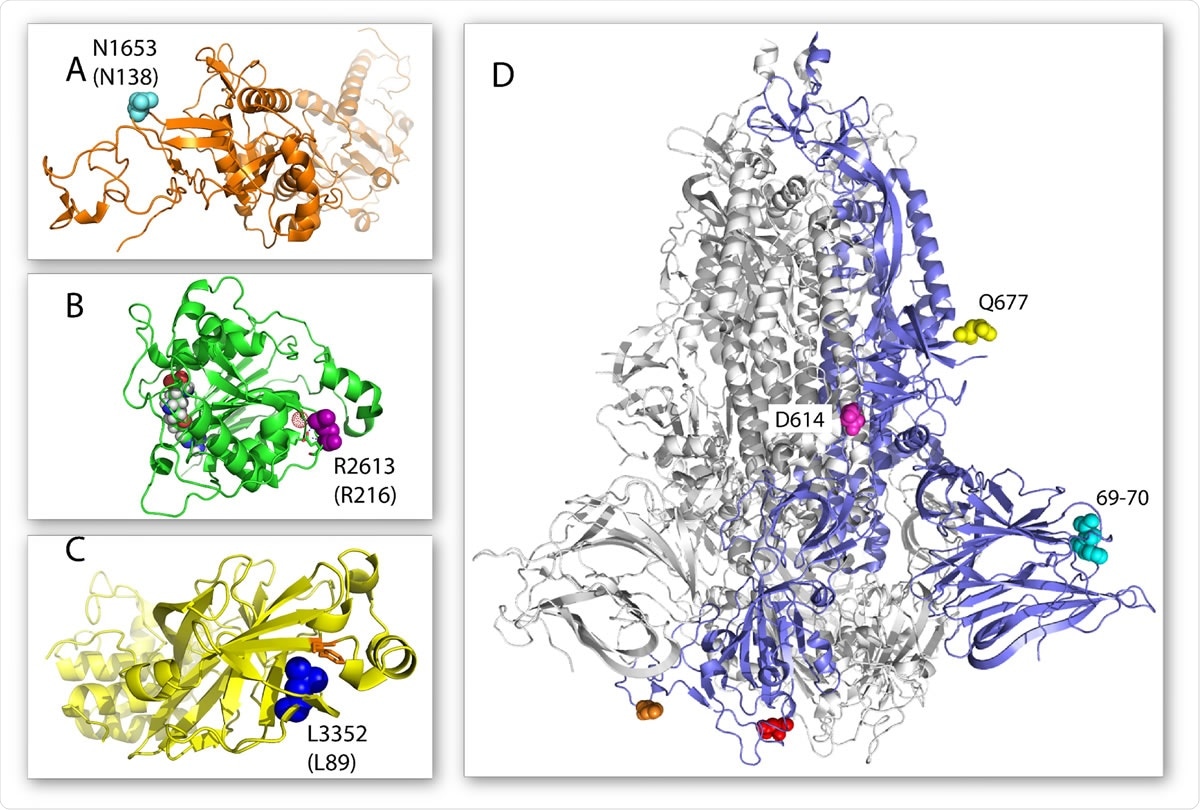

Location of select 20C-US mutations on the three-dimensional structure of their respective proteins. (A) Structure of nsp14 is shown in orange cartoon and the N138 amino acid in cyan spheres (PDB 5C8S). (B) Structure of nsp16 is shown in green cartoon and the R216 amino acid in purple spheres (PDB 6YZ1). The neighboring glutamate residue and the structured water molecule that it is predicted to hydrogen bond with are shown as green sticks and a red dot sphere, respectively. An S-adenosyl-methionine analog is shown as a space filling model in the nsp16 active site. (C) The structure of nsp5 is shown in yellow cartoon and the L89 amino acid in blue spheres (PDB 7KHP). A nearby phenylalanine available for increased hydrophobic packing is shown as orange sticks. (D) Structure of the trimeric spike protein with one monomer shown as a blue cartoon and the other two shown as gray cartoons (PDB 7JJI). The position of the Q77 amino acid is shown in spheres. Additional important mutations of the spike protein described previously are also shown: the 69-70 amino acid deletion in cyan spheres, the N501 amino acid in red spheres, the E484 amino acid in orange spheres, and the D614 amino acid in magenta spheres.

Emergence of 20C-US

The researchers now searched for all genomes from the Global Initiative for Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) database, which had the five defining mutations of the 20C-US variant. Two additional mutations were needed for this lineage, namely, ORF8:S24L and ORF1a:L3352F. The latter pair were first seen in March and April 2020 from Minnesota and Louisiana. This then gave way to five new sequences containing the first defining 20C-US mutation, namely, ORF3a:G172V, early in April.

Subsequently, several sequences from late May-early June showed the remaining four defining mutations, which seem to have either occurred simultaneously or in very rapid succession. These genomes were mostly from Texas. Following this, the new isolate appears to grow in prevalence across the country.

Strangely, however, the earliest isolate containing all five mutations was from Spain, having been obtained from a 90-year-old woman in Spain. This sequence has another mutation at all. It is very rare for mutations to reverse over time and improbable that all four mutations would arise in two different places in the same virus. The only other place where the same combination has been found was Australia, on June 24, 2020. Thus, either the Spanish or the Texan genomes could be the earliest acquisition of the four novel mutations.

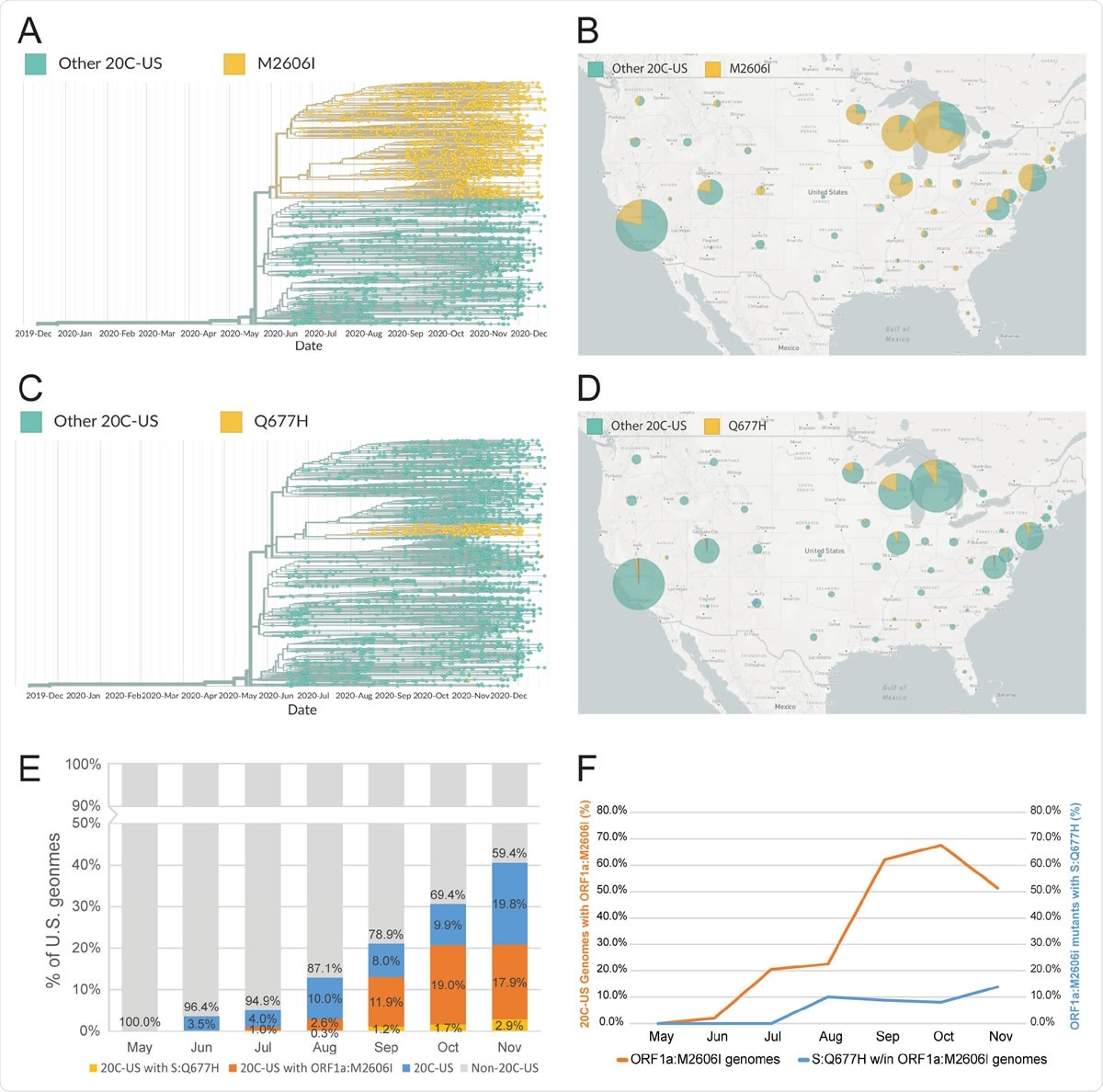

Characterization of recent mutations of the SARS-CoV-2 variant 20C-US. (A-B) Phylogenetic reconstruction and geographic visualization (during the 2-month interval of Nov. 1 to Dec. 31, 2020) of all SARS-CoV-2 variant 20C-US genomes (4683) in the GISAID database (as of Jan. 4, 2021). The ORF1a:M2606I mutant genotype is colored to distinguish it from all other genetic variants within the 20C-US tree. (C-D) Phylogenetic reconstruction and geographic visualization (during the 2-month interval of Nov. 1 to Dec. 31, 2020) for all SARS-CoV-2 variant 20C-US genomes (4683) in the GISAID database (as of Jan. 4, 2021). The S:Q677H mutant genotype is distinguished from all genetic other variants within the 20C-US tree. (E) Plot depicting the rise in percentage of 20C-US, 20C-US possessing ORF1a:M2606I, and 20C-US possessing S:Q677H genomes for all U.S. SARS-CoV-2 genomes in the GISAID database during the indicated months (as of Jan. 4, 2021). (F) Percentage of 20C-US genomes that possess the ORF1a:M2606I mutation or the percentage of ORF1a:M2606I mutants that also possess the S:Q677H mutation versus time.

Recently acquired mutations

The researchers then searched GISAID for more recent mutations in this variant, using as a stem the three defining mutations N1653D in ORF1b, G172V in ORF3a, and P67S in the N gene, along with either N:P199L or any mutations at position 2613 in ORF1b. They found over 4,600 sequences, which were phylogenetically arranged to yield a clear branch beginning at two new mutations appearing together. One was 1C4805T, a synonymous nucleotide-level mutation, and a non-synonymous ORF1a: M2606I, which first occurred together in late June 2020, in Wisconsin and Illinois. It is then observed extensively over the eastern and Midwestern USA. About half the U.S. sequences now contain the ORF1a:M2606I mutation.

In mid-August, the ORF1a:M2606I branch produced another branch containing the mutation Q677H in the spike gene, which rapidly expanded to 10% of the parent branch's genomes. While this mutation has often been observed in multiple viral lineages, it has never been part of an expanding or established branch until it was seen in this branch, perhaps because of other compensating mutations or amino acid residues in the rest of the protein. Thus, it is found in only 0.27% of global genomes, but it makes up almost 4.8% of genomes within the 20C-US lineage, indicating an 18-fold increase in prevalence. It is mainly found in the upper Midwest, namely, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan.

Further, close temporal tracking of the ORF1a:M2606I vs. the whole 20C-US genome number shows that the former shows a slowing in growth, perhaps because it has somewhat lower fitness than the latter. However, the S:Q677H mutation may have compensatory effects. While this cannot be authoritatively established at this time due to the paucity of data, further sequencing will help uncover how these two mutations interact and their effect on viral survival.

Impact of mutations

The ORF1b:N1653D and ORF1b:R2613C both affect proteins that are essential for RNA genome and transcript integrity, nsp14 and nsp16, respectively. These could alter the mutation rates and efficiency of translation as well.

The parental ORF1a:L3352F mutation in 20C-US is in nsp5 could perhaps improve protein stability, while the relatively new ORF1a:M2606I mutation affects nsp3. This is within the C-terminal domain and is involved in anchoring the viral replication transcription complex (RTC) to the endoplasmic reticulum membrane so that nsp3 can interact with other cytosolic proteins.

ORF3a: G172V is within a protein that is involved in multiple aspects of the viral life cycle at the membrane surface, as well as modulating the host cell's innate immune response and apoptosis. This mutation is within a domain that transports materials to the cell membrane and modulates interactions with viral or cellular factors.

The Q677H mutation in the spike protein, next in position to the furin cleavage site, is thought to increase the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2. This enzyme promotes the cleavage of the spike protein, which is essential for efficient viral entry into cells. The mutated residue is in a similar site to D614G, the globally dominant genome sequence.

What are the implications?

The researchers plotted the prevalence of 20C-US genomes in the USA up to December, arriving at the prediction that this would be the most common variant in the country by this point. However, it continues to make up a much larger proportion of the total infections in central and Midwest USA compared to the Northeast and Western seaboard states.

Interestingly, the increase in this strain's dominance is synchronous with the start of the second wave of COVID-19. This cannot be explained by a large-scale increase or change in population mobility patterns, whether for shopping, recreation, pharmacy, or transit station use. In fact, workplace visits increased only a little. Without these explanations to account for this variant's expansion, it seems that this trend will continue.

Further study is required to follow up on the fate of the Q677H mutation, which may be involved in viral entry. Tracing this mutation with the M2606I would help understand how this virus is evolving and how its phylogeny affects real-time outcomes of the pandemic.

On the available (admittedly scanty) evidence, it is possible that the 20C-US may be more transmissible but less virulent, a fitness advantage that could allow extensive but quiet spread.

The 20C-US variant is one of several that have rapidly acquired multiple mutations, such as the U.K. 501Y.V1 and South African 501Y.V2 strains. The researchers say this event may have caused a sudden increase in fitness, allowing it to outcompete circulating strains, just as with the D614G mutation earlier.

"The ongoing evolution of 20C-US, as well as other dominant region-specific variants emerging around the world, should continue to be monitored with genomic, epidemiologic, and experimental studies to understand viral evolution and predict future outcomes of the pandemic," said the researchers.

They caution, "Unless successful vaccination efforts can be greatly accelerated, we predict the emergence of dominant novel variants in parts of the world that are relatively isolated from other global regions, possibly including Brazil, New Zealand, the African west coast, and Japan."

Surveillance will help update vaccine development and predict major potentially dangerous shifts in viral fitness, hopefully in time to take successful countermeasures.

*Important notice: bioRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: bioRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.