As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic continues to cause severe disruptions to ordinary life the world over, scientists persist in searching for a vaccine that will help achieve herd immunity to the virus. The earliest vaccines by Pfizer, Moderna, Astra-Zeneca, and other pharmaceuticals are already being rolled out in England, the USA, China, India, and a host of other places. However, a recent preprint research paper posted on the medRxiv* server asks the question: “Is “herd immunity” to COVID-19 a realistic outcome of any immunization program with the two main vaccines currently licensed in the UK?”

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

Vaccine efficacy

R0 at the beginning of the pandemic was estimated as 2.87, but with the emergence of the D614G strain, it became a little higher, currently estimated to be 3.72. A new variant, dubbed the British variant (Lineage B.1.1.7, termed Variant of Concern VOC-202012/01), is thought to have higher transmissibility than the ancestral strain, with the R0 being 1.5 times higher. If the original value of 2.87 is used, then the current R0 for B.1.1.7 would be 4.48, while for the higher original value of 3.72, the new lineage would have an R0 of 5.80.

The researchers from the University of East Anglia noted that the efficacy of 95% is recorded in the regulatory approval documents for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, and of 70% against the symptomatic illness for the Oxford vaccine. The latter was derived from data pooled from two different dose regimens.

The Pfizer vaccine has the potential to stop viral shedding from the nose from the first-day post-vaccination, judging from the data in non-human primate studies, though human studies on this aspect have not been conducted. The Oxford Astra-Zeneca vaccine is not fully effective against asymptomatic infections. However, since these are somewhat less infectious (65%) than symptomatic cases, it still reduces transmission but may not entirely prevent it.

The Oxford vaccine is meant to prevent serious illness and symptomatic illness, though the former is more commonly achieved. It is relatively ineffective against asymptomatic infection, estimated to account for 15% of total transmission. When total incidence is considered, this brings its efficacy against all infections down to 52.5% from the pooled data.

Population coverage and protection

If the reproduction number (R0) of the virus is taken to be 2.87, the population coverage with the Pfizer and Oxford vaccines would need to be 69% and 93%, respectively, to bring the R0 below 1. Alternatively, the infection would need to spread through almost 90% of the population to achieve an R0 less than 1.

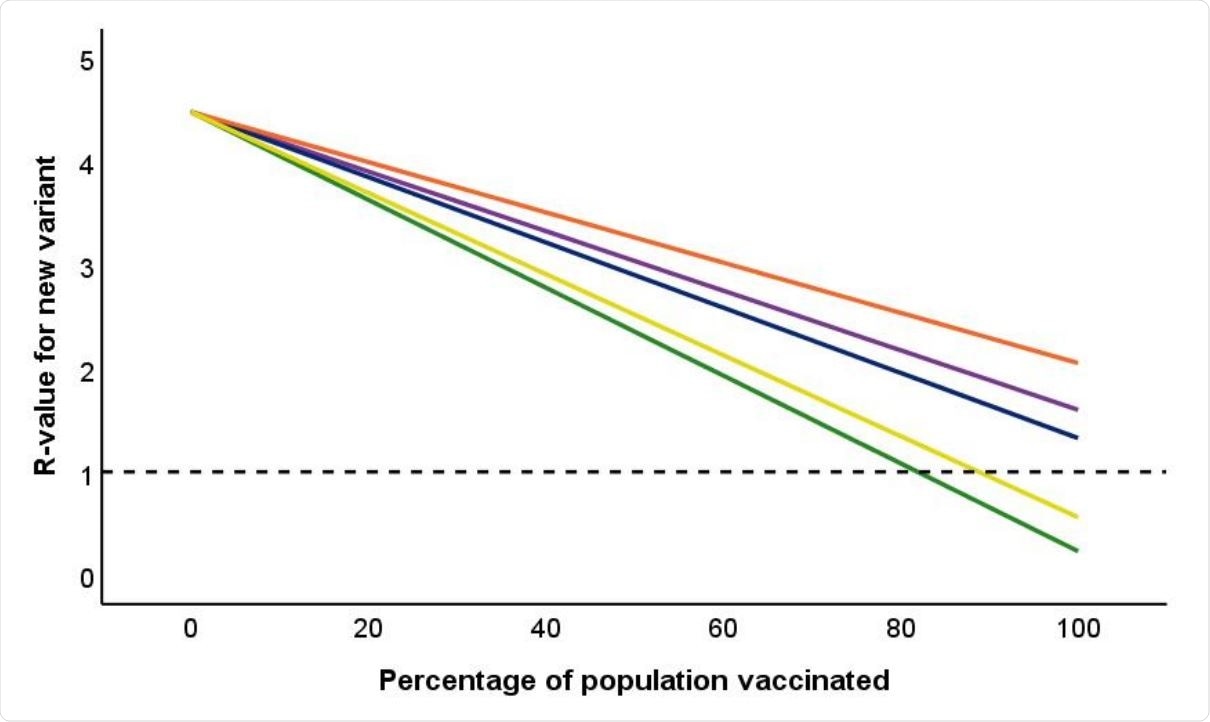

With the higher R0 of 4.48, vaccination with the Pfizer vaccine would have to cover 82% of the population to prevent further spread of this variant. Even if 100% coverage was achieved with the Oxford vaccine, the R0 would drop only to 1.325, preventing effective containment. When asymptomatic infections are included, the R0 goes up by a fifth or more, from 1.325 to 1.6, even assuming 100% coverage with this vaccine. This is because vaccinated individuals can still contract an asymptomatic infection, transmitting the virus to the unvaccinated or those with weakened immunity.

Impact of percentage of population vaccinated on overall R-value for COVID-19. Reference line is drawn at R = 1. Green line is Pfizer vaccine; Three upper lines are for Oxford vaccine. Blue: efficacy against symptomatic infection as stated in regulatory approval documents, based on pooling data for SD/SD and LD/SD regime. Purple: same pooled data, but including asymptomatic infection amongst vaccinated individuals. Orange: efficacy for licensed SD/SD regime against both symptomatics and asymptomatics observed in the phase 3 clinical trial (Voysey et al., 2021). Yellow line is equivalent information for immunity in response to natural infection based on data from the SIREN study (Public Health England, 2021c).

Vaccines authorized only for 16+

Since neither vaccine is meant to be given to children, this will push up the R0 to 2.2, say the researchers, even with 100% coverage with the Oxford vaccine. While being more effective in asymptomatic infection, the mRNA Pfizer vaccine may still be unable to fully arrest the pandemic because it is not approved for pediatric use, allowing viral spread among children.

With the Pfizer vaccine, if all adults are vaccinated and a sizable number of children become immune due to natural infection with SARS-CoV-2, the transmission should drop below sustainable levels, with the R-value below 1.

What are the implications?

The researchers conclude that vaccines in current use against SARS-CoV-2 infection can prevent serious illness in a substantial majority of cases among those who have received the vaccine. The Oxford vaccine claims only this function. With the mRNA Pfizer vaccine, non-human primate studies indicate that it may have the ability to stop the virus from being shed through the nasal secretions, thus reducing its spread.

Both vaccines will protect the most vulnerable individuals from severe or critical COVID-19. However, this hinges on adequate coverage.

Since surveys have revealed that a substantial minority of people are unwilling to take the vaccine even when available, full protection is likely to be only a dream for some time to come. However, given the potential for asymptomatic infection in those who receive the Oxford vaccine, the researchers recommend that at least among those professions that involve numerous contacts with other people, including all healthcare and social workers, a vaccine that protects against asymptomatic infection should be strongly preferred. This will avoid the false security resulting from vaccination with a vaccine that prevents symptomatic illness but may still allow transmission.

Secondly, since the Oxford vaccine allows the virus to continue circulating, it is quite possible that the virus may adapt by increased transmission efficiency or escape mutations to current neutralizing antibodies. This would make revaccinating with another vaccine that prevents infection altogether a top priority.

Finally, the evidence that the Pfizer vaccine limits asymptomatic transmission is indirect and must be updated by actual human data. The reasons for the lower efficacy of the Oxford vaccine should also be explored, as well as for the variations in the effectiveness of the two-dose regimens, where the low dose/standard dose regimen appears to have led to a higher level of protection than two standard doses. The role played by the difference in intervals between the doses should be examined.

Nonetheless, with these currently approved vaccines, “herd immunity to COVID-19 will be very difficult to achieve.” It appears likely that non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) will need to be continued for some time, at least.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.

*Important notice: medRxiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as conclusive, guide clinical practice/health-related behavior, or treated as established information.