As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), continues on its deadly course, the earliest COVID-19 vaccines to gain emergency use approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have been deployed in several countries. However, there is no way to tell precisely how long the resulting immunity will last, or even what percentage of people will be successfully immunized following vaccination.

Study aim

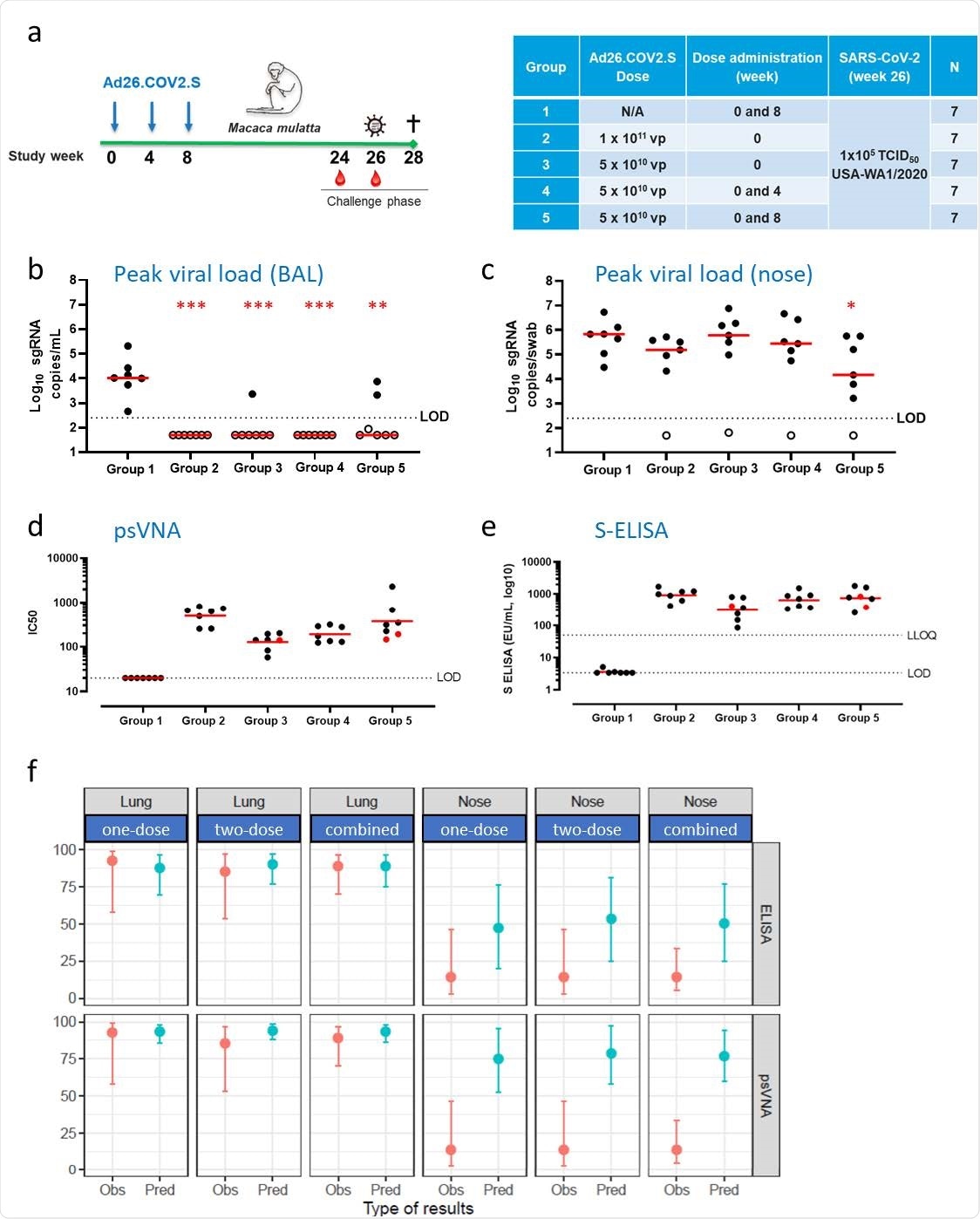

In order to understand the predictive value of immunologic markers in estimating the duration of immunity against the virus in macaques, the researchers measured the viral load, assuming that protection would correlate with undetectable viral loads.

The analysis covered all the Ad26-based vaccine candidates assuming that they would induce the same type of immune response. In earlier studies, the immunogenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S) protein has been reported, using two tests, the Pseudovirion Neutralization Assay (PsVNA) and enzyme-linked immune absorbent spot (ELISpot) assays, for humoral and cell-mediated immunity, respectively, at four weeks from vaccination.

The current study reports the results of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the spike antigen. The test used is comparable to that used to assess immunogenicity in humans.

Study findings

The researchers estimated the mean probability of protection against the virus in terms of subgenomic mRNA (sgRNA) below the limit of detection (LOD), at each level of various components of the immune reaction. They found that when there were high neutralizing antibody titers to SARS-CoV-2, viral replication in the lung and nose was prevented more effectively for all vaccine candidates as well as for Ad26.CoV2.S by itself.

Very few animals vaccinated with the Ad26.CoV2.S candidates were infected upon viral challenge, and probably, for this reason, only the logistic model for all the vaccine candidates based on Ad.26 showed a slope different from zero. The model based on Ad26.COV2.S was able to discriminate immune and non-immune status with equally high accuracy in both the lung and the nose.

They also observed that with higher levels of anti-spike binding antibodies, the level of protection against viral replication in the lung and nose increased. However, only the models based on the viral loads in the nose have a significant slope for Ad26.COV2.S as well as for all candidates together, because the lung was completely protected against infection.

These models were more discriminatory than the combined-candidate models relative to predicting protection against viral replication.

The models based on the ELISA-S assay also appeared to detect antigenicity with each vaccine candidate more sensitively than those based on psVNA, showing more marked differences between the models.

Durable protection against SARS-CoV-2 in the lower airways after vaccination with Ad26.COV2.S is predicted by binding and neutralizing antibody levels.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Good correlation of lung protection with binding and neutralizing antibodies

Both models, for binding and neutralizing antibodies, based on Ad26.COV2.S, predict 60% protection when the antibody levels are just detectable.

The cellular immune responses for the combined vaccines were not correlated well with either lung or nose protection. When examined for the Ad26.COV2.S alone, the model for lung protection alone is discriminatory, but none of the other models.

The researchers validated these findings in vaccinated rhesus macaques. The Ad26.COV2.S vaccine regimens used were one dose, two doses four weeks apart, and two doses eight weeks apart. Viral challenge via intranasal and intratracheal administration occurred at 26 weeks from the first dose.

The investigators assessed only binding and neutralizing antibodies as correlates for protection at six months from the first dose. It was observed that Ad26.COV2.S vaccinated macaques were strongly protected against viral replication in the lung, with only 3 of 28 macaques showing limited breakthrough infection. This was seen in all groups.

However, most animals continued to shed the virus in the nose after vaccination, with the most prolonged duration of shedding being in the two-dose four-week-interval group. The group that received two doses at an eight-week interval had the lowest peak viral load.

What are the implications?

The researchers observed that the predicted and observed probabilities of protection in the lung agreed well, with both the binding and neutralizing antibodies to the spike protein, with the one-dose regimens. Comparably high prediction accuracy is observed for the two-dose regimens as well.

Thus, “the predictions based on binding and neutralizing antibodies show a remarkable correspondence to the observed protection proportion in the lung, indicating that the potential correlates of protection identified early after vaccination can be used to predict durable protection against infection of the lower airways in rhesus macaques.”

The agreement is less robust when it comes to protection in the nose, at predicted levels of 50% and 75% protection based on binding and neutralizing antibody levels, respectively, but observed protection in only 14%. This may indicate that systemic antibody levels are associated with protection in the nose in the early phase of infection but do not mediate protection at this site themselves.

The researchers conclude that one or two doses of this vaccine candidate protect rhesus macaques against viral replication in macaques' lungs. This could correlate with long-term immunity in humans following vaccination, with an anamnestic response being likely that would enhance immunity still further. In fact, early studies in humans show an efficacy of 85%, further confirming the utility of the macaque model to predict the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines.

With longer follow-up, the extent to which macaque-based predictions are in tune with observations of immunity in humans could allow the duration of protective immunity in humans to be predicted from immunogenicity data. This will be of special importance in the coming days when placebo recipients can no longer be followed up because they will become part of the vaccine recipient group.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources