Researchers in the United States and Canada have mapped the presence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in the brains of people who died from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Geidy Serrano from Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Sun City, Arizona and colleagues found that infection with SARS-CoV-2 can result in acute neuropathology.

The findings supported other studies suggesting that neurological signs and symptoms are not generally the result of direct viral invasion of the brain. Rather, they appear to be linked to systemic reactions such as coagulopathy, autoimmune responses, organ failure and sepsis.

The team says much remains to be understood, including the interactions between viruses and hosts that influence brain invasion and whether the virus is cleared from the brain following acute illness.

A pre-print version of the research paper is available on the medRxiv* server, while the article undergoes peer review.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

SARS-CoV-2 is related to other brain-invading coronaviruses

Given that the SARS-CoV-2 virus is related to coronaviruses that have previously been shown to invade the brain, it is likely that SARS-CoV-2 shares similar capabilities, say the researchers.

The human coronavirus OC43 (HCoV-OC43) has been found to cause acute encephalomyelitis in children, while other coronaviruses have been associated with demyelinating disease in animal studies.

The HCoV-OC43 virus and another strain – HCoV-229E – have also been detected in human brains obtained from multiple banks throughout Europe, the UK and the United States, suggesting that coronaviruses are capable of invading and persisting in the central nervous system (CNS).

Many clinical reports and reviews have collectively described a wide range of SARS-CoV-2-associated neurological signs, symptoms and syndromes. However, it remains unclear what fraction have been due to direct viral CNS invasion as opposed to indirect effects caused by systemic reactions to critical illness.

Autopsy reports have described meningitis and encephalitis in a small fraction of patients dying from COVID-19 and, more frequently, ischemic and hemorrhagic cerebrovascular lesions. However, these findings have not been supported by direct evidence of SARS-CoV-2 in the CNS.

“Still critically lacking is a comprehensive tissue-based survey of the CNS presence or specific neuropathology of SARS-CoV-2 in humans,” says Serrano and colleagues.

What did the researchers do?

Using reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays, the researchers comprehensively surveyed the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in 16 brain regions of 20 people who had died from COVID-19.

The subjects were aged 38 to 97 years (mean age 77 years), and 11 were male.

The majority of those who died from COVID-19 exhibited typical age-related neuropathologic features.

Neuropathology was severe in only two individuals, one with a large acute cerebral infarction and one with hemorrhagic encephalitis. In both cases, the neuropathology was unequivocally linked to COVID-19.

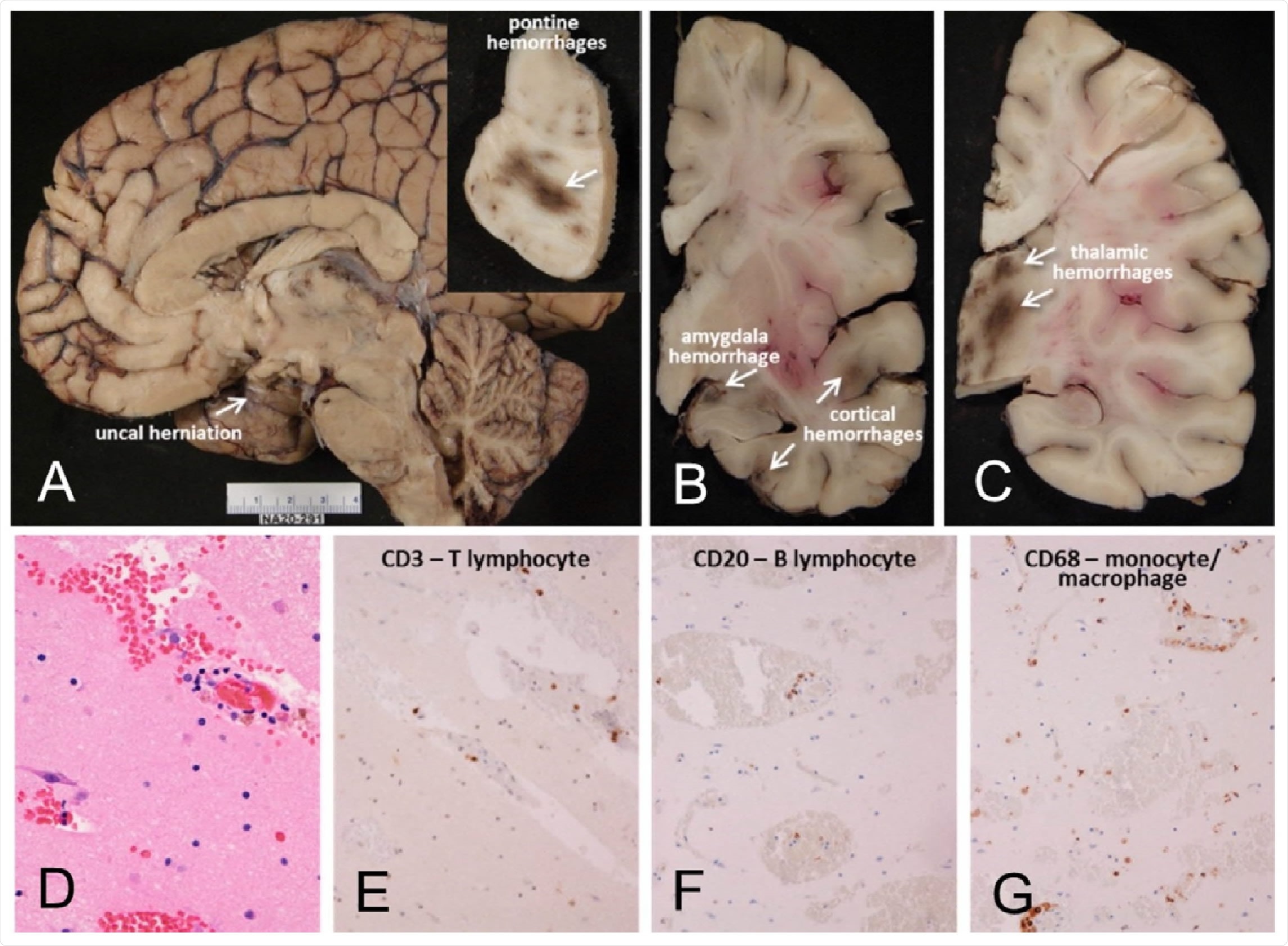

Mayo Clinic Case M10, a male in his 30s. Neuropathological gross examination consistent with encephalitis-associated brain swelling causing transtentorial uncal herniation (A) and associated with acute hemorrhages (arrows A inset, and in B and C). Microscopic examination of semiadjacent temporal lobe sections show microscopic hemorrhage (D; H & E stain) and neuropil infiltration w and B-lymphocytes and macrophages (E-G)

However, the majority of the remaining subjects had non-specific histopathology. Aside from the encephalitis case and one case where two microglial nodules were observed in the posterior medulla, there was no clear evidence of the classical neuropathology of viral CNS infections.

“The findings of this study are generally in agreement with previously reported autopsy examinations of the brains of COVID-19 disease subjects, in that serious complications like encephalitis and large acute infarctions were present in relatively few subjects,” says the team.

Was SARS-CoV-2 RNA found?

The study identified four individuals (20%) who had SARS-CoV-2 RNA in one or more brain regions, including the olfactory bulb, amygdala, entorhinal area, temporal and frontal neocortex, dorsal medulla and leptomeninges.

The team says the relatively low rate of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in brain tissue is also in agreement with previous studies. The rate of 20% observed here compares with a mean of 22% across the total number of individuals included in 16 previously published studies.

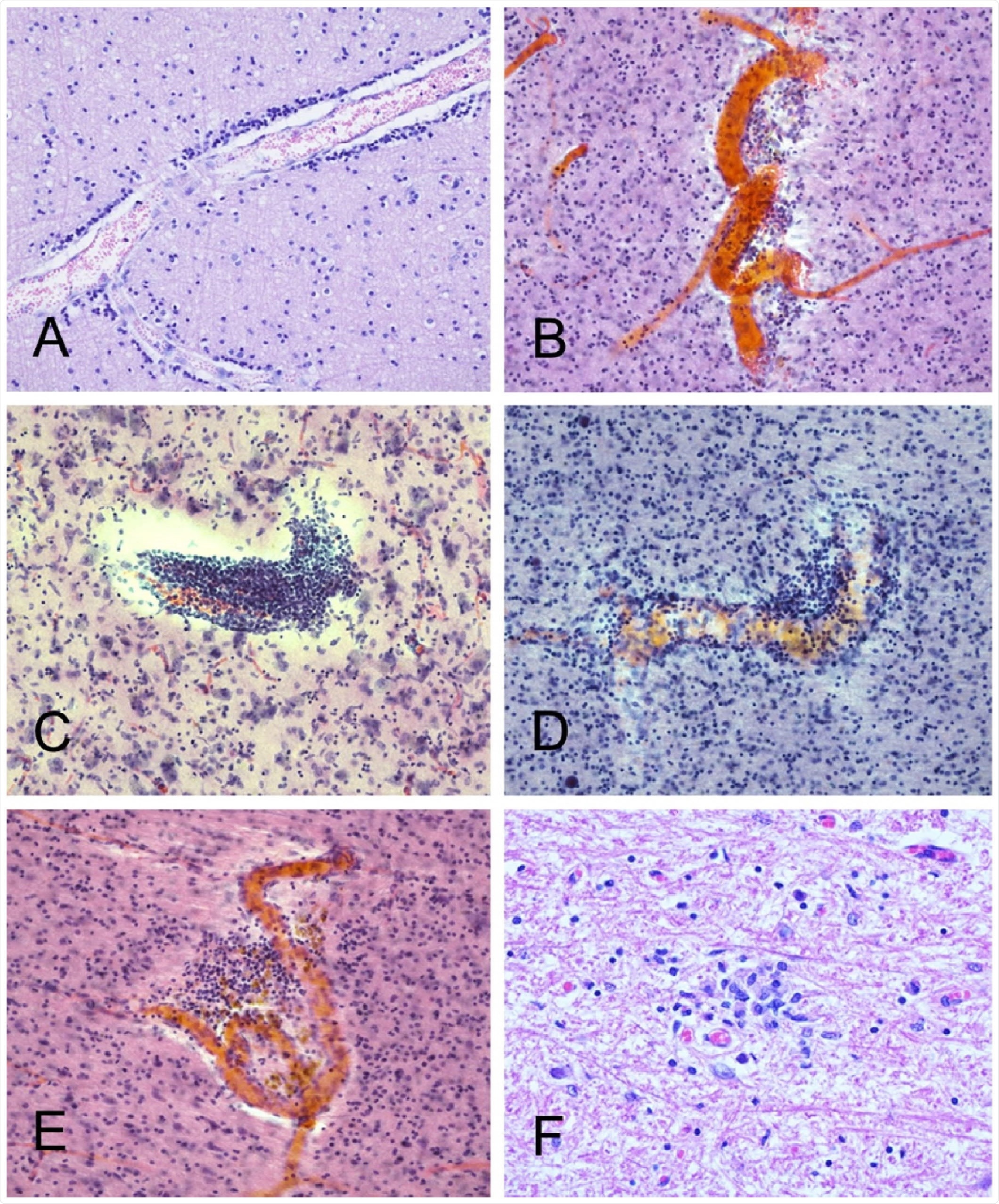

Several cases had occasional perivascular mononuclear cell aggregates, in both gray and wh matter. Shown are examples from BSHRI Case B4, a male in his 80s(A), Case B2, a female in her 70s Case B6, a male in his 70s (C), Case B8, a male in his 80s(D), and Case B9, a male in his 70s (E). Also is a microglial nodule in the posterior medulla in the region of the nucleus gracilis, in BSHRI Case B6 (F) Images are from H & E-stained 80 μm thick sections (B-E) or 6 μm paraffin sections (A, F).

What are the implications of the study?

“These results confirm the growing consensus that most of the reported COVID-19 associated neurological signs and symptoms may be due, not to direct viral brain invasion, but to systemic reactions such as coagulopathy, sepsis, autoimmune mechanisms or multiorgan failure,” writes the team.

The researchers say that like other human coronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2 can lead to acute or subacute neuropathology.

However, much still needs to be understood, including the virus–host interactions that influence CNS invasion and whether the virus is cleared following acute illness.

“Further investigations will hopefully enable the development of improved surveillance, diagnostic and therapeutic strategies,” concludes Serrano and colleagues.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Geidy E. Serrano GE, et al. Mapping of SARS-CoV-2 Brain Invasion and Histopathology in COVID-19 Disease. medRxiv, 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.15.21251511, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.15.21251511v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Serrano, Geidy E, Jessica E Walker, Cécilia Tremblay, Ignazio S Piras, Matthew J Huentelman, Christine M Belden, Danielle Goldfarb, et al. 2022. “SARS-CoV-2 Brain Regional Detection, Histopathology, Gene Expression, and Immunomodulatory Changes in Decedents with COVID-19.” Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology 81 (9): 666–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnen/nlac056. https://academic.oup.com/jnen/article/81/9/666/6639867.