Researchers in the UK have provided important insights into the impact that vaccination against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) – the agent that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) – may have on infection rates, disease prevalence and immune escape by the virus.

The study was conducted by members of the JUNIPER consortium (Joint UNIversities Pandemic and Epidemiological Research), which brings together leading mathematical and statistical modeling experts from seven universities in the UK.

Julia Gog from the University of Cambridge and colleagues say the study suggests that vaccination focused on reducing prevalence may be more effective at reducing disease than directly vaccinating vulnerable people.

The findings also suggest that the risk of SARS-CoV-2 escaping vaccine-induced immunity is most likely to occur at intermediate levels of vaccination.

"This work demonstrates a key principle that the careful targeting of vaccines towards particular population groups could reduce disease as much as possible, whilst limiting the risk of vaccine escape," writes the team.

A pre-print version of the research paper is available on the medRxiv* server, while the article undergoes peer review.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Multiple vaccines are already being rolled out

In response to the global public health risk posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers have developed multiple vaccines in record time that have been approved for emergency use and rolled out in mass vaccination programs.

However, the rapid evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has led to the emergence of new variants that are more transmissible, cause more lethal disease, and potentially threaten vaccines' effectiveness.

The widespread deployment of highly effective vaccines, particularly while the infection is still widespread, could quickly exert pressure on the virus to select mutations that confer escape from vaccine-induced immunity.

"However, the strength of this selection and the likelihood of vaccine escape is unknown at this time," says Gog and the team.

Vaccine shortages prompt prioritization strategies

In many countries, vaccine shortages have placed authorities under pressure to prioritize the best order of prioritization for vaccination.

In the UK, the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) has advised that the prevention of COVID-19-related deaths and the protection of health and social care staff should be the first priorities of the vaccination program.

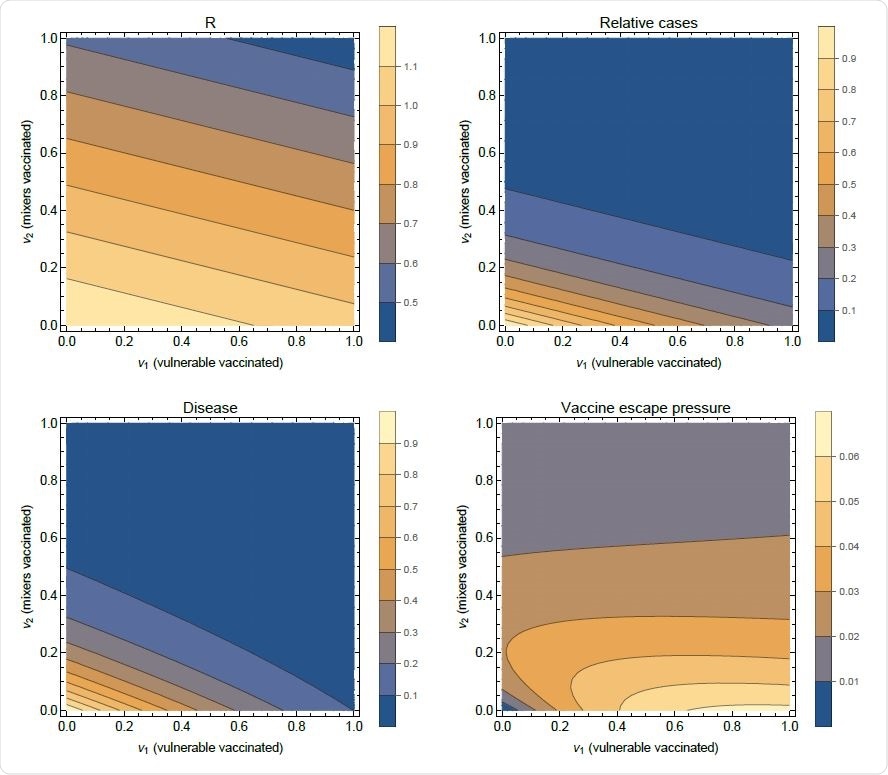

Summary outputs

However, "at the time of the initial prioritization, extremely limited data were available from clinical trials on vaccine efficacy for preventing infection and onward transmission," says Gog and colleagues.

For the second phase of the vaccination program, the Department for Health and Social Care asked JCVI to provide advice on the optimal strategy to further reduce COVID-19-related mortality, morbidity and hospitalization.

The JCVI recommended proceeding with age-based prioritization, with operational considerations as part of the justification on account of the speed of vaccine uptake being paramount.

Where does the current study come in?

In the current study, the team asked how vaccine escape risk might modulate the optimal vaccine priority order.

"In particular, if infection in vaccinated individuals contributes to pressure to generate vaccine escape, how do the risks depend on the parts of the population that have been vaccinated?" write the researchers.

Gog and colleagues developed and analyzed a population model with differing vulnerability and contact rates to understand the relationships between epidemiological regimes, vaccine efficacy and vaccine escape.

Population variability in vulnerability and mixing was captured by dividing the model population into two halves: those vulnerable to disease (vulnerable group) who have fewer contacts with non-vulnerable individuals who have more contacts (mixer group).

What did the model show?

Overall, the effective reproduction ratio decreased as the number of people vaccinated increased, providing vaccination had a transmission-blocking effect. The overall number of severe infections also decreased as the number of people vaccinated increased.

The researchers say it is intuitive that vaccinating more people in any group would decrease cases in that group, owing to the transmission-blocking and disease-blocking effects of vaccination.

"However, the question remains of which group it would be most effective to vaccinate to reduce severe disease," they add.

Gog and colleagues explored this question by considering a situation in which only enough vaccine is available to vaccinate a proportion of either group.

Overall, the results suggested that vaccinating the mixers is more effective at reducing the total amount of disease than vaccinating the vulnerable individuals.

The researchers say that although it may seem intuitive to focus vaccination on the vulnerable group, the results are hinged on the transmission-blocking effects of vaccination.

"Bringing down R overall means fewer cases in the vulnerable and the most efficient way to do that is to vaccinate the mixers," they write. "Overall, the results in this model show that the effects of vaccination on the reduction of cases can give a counter-intuitive optimal strategy: vaccinate the mixers to best protect the vulnerable."

What about vaccine escape pressure?

When no mixers were vaccinated, then vaccinating more vulnerable people generally increased vaccine escape pressure. However, when no vulnerable people were vaccinated, then vaccinating the mixers initially increased vaccine escape pressure, but later decreased it as vaccine uptake increased among the mixers.

"Increasing vaccination of mixers increases the proportion of cases who are vaccinated, but decreases the overall absolute number of cases," says Gog and the team.

The researchers say the highest risk for vaccine escape can therefore occur at intermediate levels of vaccination.

"In particular, vaccinating most of the vulnerable and few of the mixers could be the most risky for vaccine escape," they write.

What do the authors advise?

The researchers say the model considered here illustrates the key principle that carefully targeting vaccines towards particular groups allows case numbers to be reduced, while limiting the risk of vaccine escape.

"We hope that the proposal of general principles under this abstracted system will motivate further investigation under more detailed models," they write.

"We recommend that vaccine escape risks should be included as part of considerations for vaccine strategies, and that further work is urgently needed here," concludes the team.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources