Whenever there is a change in any system, it will cause other changes to reach a balance or equilibrium, generally at a point different from the original balance. Although this principle was originally posited by the French chemist Henry Le Chatelier for chemical reactions, this theory can be applied to almost anything else.

In an essay published on the online server Preprints*, Eleftherios P. Diamandis of the University of Toronto and the Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, argues that changes caused by humans, to the climate, and everything around us will lead to changes that may have a dramatic impact on human life. Because our ecosystems are so complex, we don’t know how our actions will affect us in the long run, so humans generally disregard them.

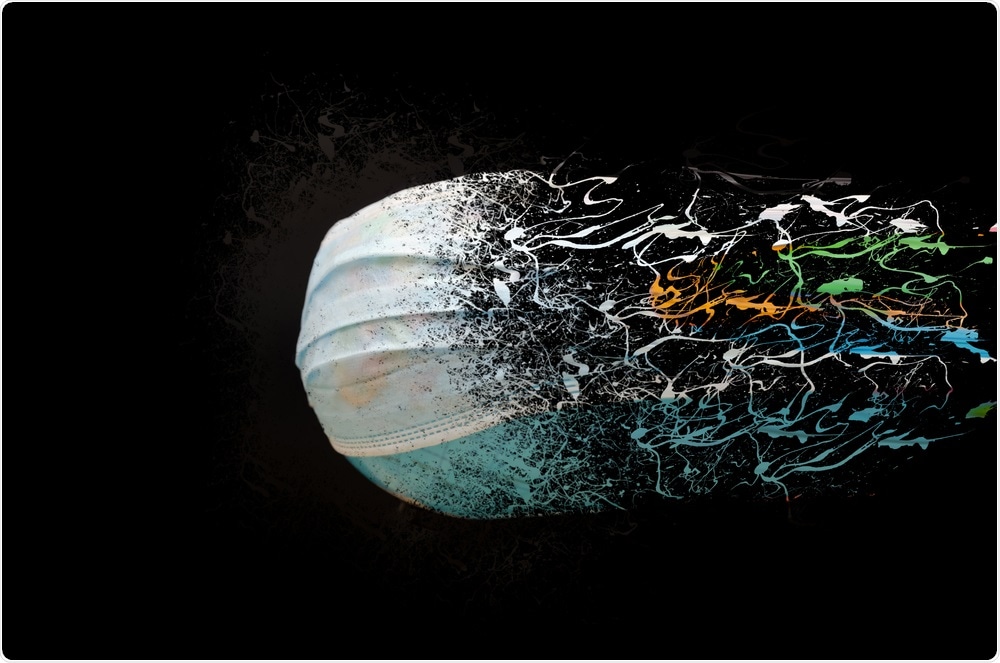

The Mother of All Battles: Viruses vs. Humans. Can Humans Avoid Extinction in 50-100 Years?. Image Credit: Yaroslau Mikheyeu / Shutterstock

Changing our environment

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Everything around us is changing, from living organisms to the climate, water, and soil. Some estimates say about half the organisms that existed 50 years ago have already become extinct, and about 80% of the species may become extinct in the future.

As the debate on global warming continues, according to data, the last six years have been the warmest on record. Global warming is melting ice, and sea levels have been increasing. The changing climate is causing more and more wildfires, which are leading to other related damage. At the same time, increased flooding is causing large-scale devastation.

One question that arises is how much environmental damage have humans already done? A recent study compared the natural biomass on Earth to the mass produced by humans and found humans produce a mass equal to their weight every week. This human-made mass is mainly for buildings, roads, and plastic products.

In the early 1900s, human-made mass was about 3% of the global biomass. Today both are about equal. Projections say by 2040, the human-made mass will be triple that of Earth’s biomass. But, slowing down human activity that causes such production may be difficult, given it is considered part of our growth as a civilization.

Emerging pathogens

Although we are made up of human cells, we have almost ten times that of bacteria just in our guts and more on our skin. These microbes not only affect locally but also affect the entire body. There is a balance between the good and bad bacteria, and any change in the environment may cause this balance to shift, especially on the skin, the consequences of which are unknown.

Although most bacteria on and inside of us are harmless, gut bacteria can also have viruses. If viruses don’t kill the bacteria immediately, they can incorporate into the bacterial genome and stay latent for a long time until reactivation by environmental factors, when they can become pathogenic. They can also escape from the gut and enter other organs or the bloodstream. Bacteria can then use these viruses to kill other bacteria or help them evolve to more virulent strains.

An example of the evolution of pathogens is the cause of the current pandemic, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Several mutations are now known that make the virus more infectious and resistant to immune responses, and strengthening its to enter cells via surface receptors.

The brain

There is evidence that the SARS-CoV-2 can also affect the brain. The virus may enter the brain via the olfactory tract or through the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) pathway. Viruses can also affect our senses, such as a loss of smell and taste, and there could be other so far unkown neurological effects. The loss of smell seen in COVID-19 could be a new viral syndrome specific to this disease.

Many books and movies have described pandemics caused by pathogens that wipe out large populations and cause severe diseases. In the essay, the author provides a hypothetical scenario where a gut bacteria suddenly starts producing viral proteins. Some virions spread through the body and get transmitted through the human population. After a few months, the virus started causing blindness, and within a year, large populations lost their vision.

Pandemics can cause other diseases that can threaten humanity’s entire existence. The COVID-19 pandemic brought this possibility to the forefront. If we continue disturbing the equilibrium between us and the environment, we don’t know what the consequences may be and the next pandemic could lead us to extinction.

The author

Eleftherios Phedias Diamandis, is a Greek Cypriot-Canadian biochemist who specializes in clinical chemistry. He is Professor & Head of Clinical Biochemistry in the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology at the University of Toronto in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. He is also Division Head of Clinical Biochemistry at Mount Sinai Hospital and Biochemist-in-Chief at the University Health Network, located in Toronto.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources