The COVID-19 pandemic has ravaged the world, with over 3 million deaths out of 143 million documented infections globally. Caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is primarily respiratory but leads to severe or life-threatening disease in a significant minority of patients.

Most patients have asymptomatic or very mild infections, but about 15% develop moderate or severe symptoms. These may lead to extensive pneumonia, marked difficulty in breathing, hypoxemia, high levels of inflammation, acute respiratory distress syndrome, clotting disorders, disturbances of heart function, and death, or long-term sequelae in a proportion of those who survive.

COX inhibitors

COX inhibitors include many drugs which inhibit a key enzyme of the pathway by which the lipid molecule called arachidonic acid is metabolized to the multifunctional inflammatory mediators called prostaglandins. Prostaglandins regulate coagulation, blood flow, and inflammation, among other processes.

COX has two human isoforms, COX-1, which is expressed in all tissues and is responsible for the production of homeostatic prostaglandins that, for instance, maintain the integrity of the gut epithelium. Its inhibition is thought to be the reason for most of the ill effects caused by NSAIDs, such as peptic ulceration, bleeding from the gut, hemorrhagic stroke, kidney dysfunction, and bronchoconstriction.

COX-2 is not constitutively expressed but is induced by cytokines, which are cell signaling molecules. The result is the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

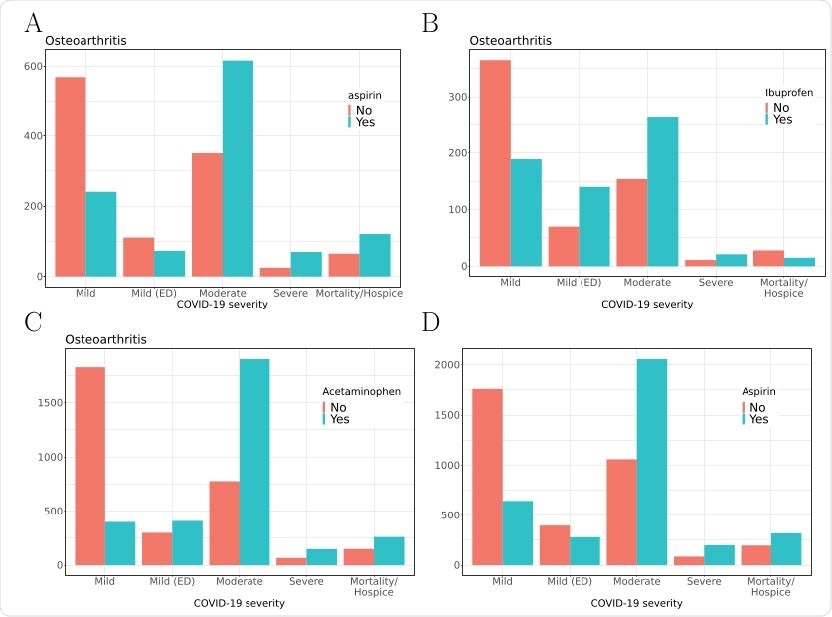

COVID-19 severity in a subcohort of osteoarthritis patients taking vs. not taking A) aspirin, B) ibuprofen or C) acetaminophen; and D) entire COVID-19 cohort taking vs. not taking aspirin. Severity of COVID-19 by group is shown on the x-axis, and number of patients is shown on the y-axis.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Adverse effects of NSAIDs

NSAIDs are potent pain-relievers. However, they are also responsible for significant numbers of hospitalizations because of the severe side effects.

COX-2 inhibitors were initially developed to avoid the gastrointestinal complications of using NSAIDs. However, their use increases the risk of cardiovascular adverse events, including heart attacks and strokes, just as with non-selective NSAIDs.

NSAIDs also suppress immune function by inhibiting neutrophil adherence, reducing neutrophil oxidant production and granule release, triggering neutrophil apoptosis, and suppressing antibody production.

They may prevent the recognition of fever and pain during the course of severe infections, including community-acquired pneumonia. Some work suggests that when used early in this condition, NSAIDs not only delay diagnosis but are linked to a more severe course of pneumonia.

The controversy surrounding this work has not been resolved, though the conclusions are biologically plausible.

Indomethacin and naproxen are among the NSAIDs which seem to directly antagonize SARS-CoV-2. Conversely, ibuprofen seemed to worsen clinical severity in a French study.

The OpenSAFELY-based study from early in the pandemic, used data from 40% of English patients over 3.5 months in 2020. It showed that the use of NSAIDs within four months of March 1, 2020, did not increase COVID-19-related deaths in either of two groups: one with rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis and one with a history of regular NSAID use within four months of the start of the study.

Other small studies showed that aspirin use in patients within 24 days after admission, or seven days before admission, reduced both the severity and fatality rate of COVID-19.

Study details

The current observational study, which seeks to understand the impact of seven NSAIDs and acetaminophen on COVID-19 severity, uses data from the largest cohort of US COVID-19 cases and controls. This is stored in a centralized database of electronic health records (EHR).

The study Included over 250,000 participants with COVID-19 in a retrospective study, with a mean age of 42 years, of which 54% were female.

They were classified according to certain common indications for NSAID use, such as angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, osteoarthritis, fever, pain, migraine, and rheumatoid arthritis.

COVID-19 patients with these indications were classified as users or non-users of NSAIDs, and their clinical course was assessed.

The study showed that five of the eight COX inhibitors significantly increased the severity and mortality rates in COVID-19 patients.

What were the results?

Severe COVID-19 was linked to the use of aspirin, ibuprofen, and acetaminophen, as well as to other more conventional indicators like age, male sex, and a higher Charlson comorbidity index (CCI). In patients with osteoarthritis or other similar indications, aspirin use was associated with 3.3 times higher odds for severe COVID-19 compared to those patients not on this drug.

Severity associated with use

For five of eight tested COX inhibitors, the severity of the disease was increased. In both the moderate and severe COVID-19 categories, many more patients were recorded as using these drugs.

These included aspirin, ibuprofen, ketorolac, naproxen, and acetaminophen. Moreover, aspirin and acetaminophen were associated with higher mortality.

For instance, with aspirin, the number of patients with moderate COVID-19 on aspirin was twice the number not on this drug. With ibuprofen and acetaminophen, the corresponding ratios were 2:1 or greater.

The odds ratios for increased severity of COVID-19 were highest with acetaminophen, at between 6-fold and 9-fold higher odds compared to non-users.

In the cohort of non-survivors, these associations were equally significant.

No association with severity

Conversely, diclofenac, meloxicam, and celecoxib were not associated with a similar increase in disease severity. It is noteworthy that all three are selective COX-2 inhibitors.

Unlike earlier studies on NSAID use in CAP, there was no correlation of NSAID use with neutrophil counts in COVID-19, and other immune cell parameters were not evaluated due to the lack of data.

What are the implications?

Acetaminophen has a different mode of action than other NSAIDs and is linked to reduced mortality in patients with a critical illness. Anecdotal evidence that ibuprofen use worsened the condition of patients with critical COVID-19, added to the above work on CAP, has led to the current recommendation against its use in symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection.

However, the findings do not support current guidelines allowing the use of acetaminophen in symptomatic COVID-19 patients.

Aspirin is the least selective of the NSAIDs, and celecoxib is among the most, as well as having additional activity unrelated to COX inhibition. Thus, this group of molecules may not have a homogeneous adverse effect profile.

The study relied on the known use of NSAIDs. Still, since many of these are available over the counter, unrecorded use is quite likely in many of the ‘controls,’ which would confound the observed associations.

“While our findings suggest the importance for clinicians to carefully consider which COX inhibitor to prescribe, additional research will be required to confirm our results in other settings and to address the question of whether different COX inhibitors have different adverse effect profiles in treating COVID-19.”

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources