Emerging variants of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) are causing a third wave in Europe, and an interesting development has been observed.

As transmissible variants and vaccinations have increased, several European countries have experienced a second and third wave of the pandemic without a proportional increase in disease severity and mortality.

A promising development has prompted a study premised on an additional factor that can influence how the virus affects the population.

The concept of having a higher immune defense against the virus is predicated on SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells, which progressively develop based on natural exposure to low viral doses.

Recent studies have suggested that low-dose viral particles enter the respiratory and intestinal tract and can induce the T cell memory response without inflammation occurring, resulting in varying degrees of immunization. This lack of inflammatory response could be the cause of a disproportionate level of COVID-19 rates and disease severity and mortality in the population.

A recent analysis of German data found a decline in fatality rates from COVID-19 in all age groups, including older age groups. This can also be confirmed by the surveillance reports by the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), who have relayed that a majority of European countries have experienced high rates of COVID-19 in 2021 without a proportional increase in mortality rates.

The hypothesis of low-virus doses leaking from masks which may reduce disease severity in those who are subsequently infected, has been proposed to explain the possible increase in the rates of asymptomatic infections.

The Italian authors of this paper, published in the journal Viruses, have taken this hypothesis and expanded it to include viral particles suspended in the air or on inanimate objects as a possible source of T cell immunity due to the repeated low-dose exposure, potentially explaining virus immunity found in non-infected individuals.

Disease severity trends

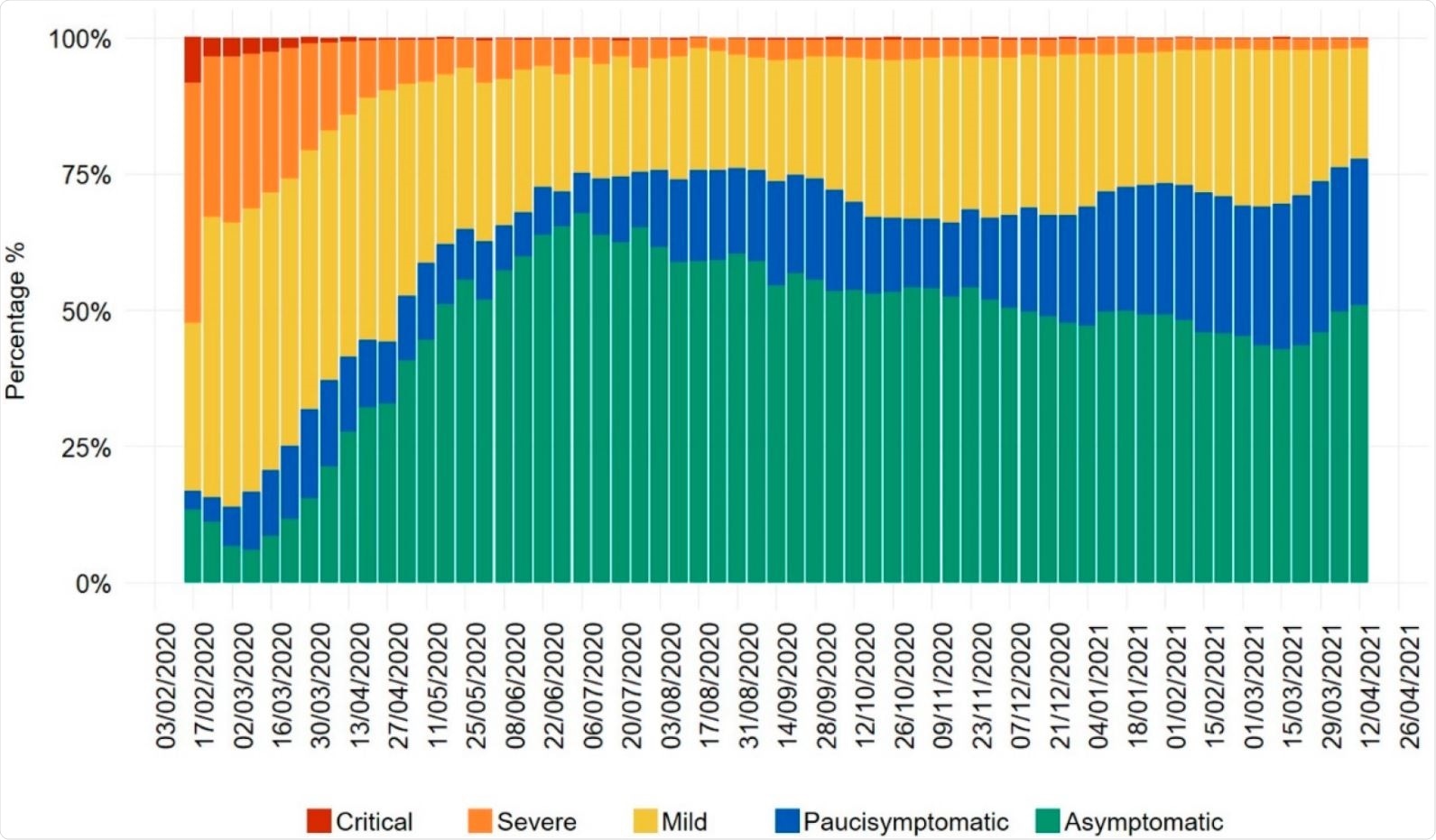

COVID-19 distribution in Italy from February 2020 to April 2021 illustrates an increase in asymptomatic and paucisymptomatic cases, whereby more individuals with the infection either presented with no symptoms or a few symptoms such as malaise (seen in Figure 1).

Epidemiological data of the Italian National Institute of Health (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome, Italy) showing the clinical status of COVID-19 patients from January 2020 to April 2021. Colored bars represent the percentage of cases, respectively, with critical clinical conditions (top bars, dark red, clinical manifestations affecting the respiratory tract and/or other organ systems that require hospitalization in intensive care), with severe disease (orange bars, clinical manifestations affecting the respiratory tract and/or other organ systems that require hospitalization, not in intensive care), with mild disease (yellow bars, clinical manifestations affecting the respiratory tract and/or other organ systems that would not normally require hospitalization), with paucisymptomatic disease (blue bars, mild and general symptoms e.g., general malaise, fever, fatigue, etc.), and with asymptomatic disease (green bars, no apparent signs or symptoms of disease). Raw data in the xlsx format are publicly available at the Istituto Superiore di Sanità website www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/sars-cov-2-dashboard (accessed on 23 April 2021).

The development of natural immunity in the population can explain the rise in SARS-CoV-2 infections with new variants being transmitted easily, but resulting in low numbers of severe diseases and larger numbers of mild infections.

This result can cause the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic to transition into an endemic, similar to common cold coronaviruses, with the possibility that the virus can lose its potency. The low-dose exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in the environment may therefore help to reduce the severity of the infection.

How low virus doses help with immunity

With studies suggesting that a higher T cell response can be achieved by low levels of antigenic stimulation, the concept of low antigen doses has gained interest in vaccine development. Mouse-adapted models of MERS and SARS have confirmed that low virus doses result in milder disease manifestations, and this was also seen in hamster models and ferrets infected with SARS-CoV-2.

The Italian study proposes this immunity increase through low virus doses entering via the lungs and respiratory tract or the gastrointestinal system through touching food with contaminated hands.

Due to hand-washing not being a total sterilization method to eliminate viral particles, this can contribute to the small doses being introduced into the system and into the gut, whereby epithelial cells expressing angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) can be infected by SARS-CoV-2.

In contrast to the respiratory tract, intestinal exposure has been shown to be less pathogenic, which may explain the asymptomatic cases of COVID-19.

T cell responses have been shown to be polyfunctional, stable, and can last for six months after infection. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells with a stem-like memory phenotype have been identified in recovered COVID-19 patients, highlighting the long-lasting impact of memory T cells in the immune response after the viral infection.

A key study of Swedish subjects found that these SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells were found in 67% of exposed family members who had shared a household with the infected individual, which further adds to the theory of immunity after repeated exposure to low viral doses.

While high doses of the virus reaching the pulmonary alveoli can result in the death of airway epithelial cells and trigger the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which recruit immune cells to the lungs, low doses that reach the same area are less likely to trigger this massive response.

The absent inflammatory response associated with low doses allows the viral antigens to be processed and presented to CD4+ or CD8+ T cells through the major histocompatibility complex, which can result in the development of an adaptive immune response against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

The future of COVID-19

With surgical masks being more prominently worn by the public, the low doses which can leak out can act as a ‘virolation’ process that can increase asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 cases and impact overall immunity.

The U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has stated that the relative risk of viral transmission from inanimate objects from SARS-CoV-2 is low compared to direct contact, including droplet and air transmission.

Additionally, a systematic analysis on virus stability has also indicated the concentration of the virus on plastic and steel decreases to a greater extent after 72 hours.

The future of the pandemic may lie in easing into an endemic whereby the virus may still be true and well with variants emerging, but the low doses from infectious individuals and from inanimate objects may help with asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic presentations of the infection.

This may work similar to the common cold and enable a more progressive future with an increase in natural immunity for populations worldwide.

Journal reference:

- De Angelis, M., Francescangeli, F., Rossi, R., Giuliani, A., De Maria, R. and Zeuner, A., 2021. Repeated Exposure to Subinfectious Doses of SARS-CoV-2 May Promote T Cell Immunity and Protection against Severe COVID-19. Viruses, 13(6), p.961., DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/v13060961, https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/13/6/961/htm