Scientists from the Queen’s University, Canada, have recently uncovered the broad-spectrum antiviral activity of epigallocatechin gallate, a bioactive compound from green tea, against highly pathogenic coronaviruses found in humans and animals. The compound prevents viral infection by interfering with virus-host cell attachment. The study is currently available on the bioRxiv* preprint server.

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has been linked to over 179 million infections and more than 3.89 million deaths worldwide as of June 23, 2021.

SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped RNA virus that primarily spreads from person to person via large respiratory droplets and aerosols. The infection initiates with the binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).

Most human viruses, including coronaviruses, initiate the host cell entry process through attachment with low affinity and high avidity cell surface glycans, such as heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Recently, heparan sulfate has been identified as a co-factor required for SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The green tea-derived bioactive polyphenolic compound epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) is known to exert potent antiviral activity against many DNA and RNA viruses primarily by inhibiting the viral attachment to cellular glycans. The antiviral activity of EGCG has been demonstrated against herpes simplex virus type 1, hepatitis C virus, and influenza A virus.

In the current study, the scientists have evaluated the antiviral activity of EGCG against murine (rodent), vespertilionine (bat), and human coronaviruses.

Study design

Viral infectivity and cytotoxicity were assessed by pre-incubating human common cold coronaviruses 229E and OC43, murine hepatitis virus, SARS-CoV-2 spike-expressing vesicular stomatitis virus, and coronavirus spike-expressing pseudotyped lentiviral particles with EGCG and subsequently infecting cells with pre-incubated viruses.

In addition, time-of-addition experiments were carried out to determine the mode of action of EGCG.

Important observations

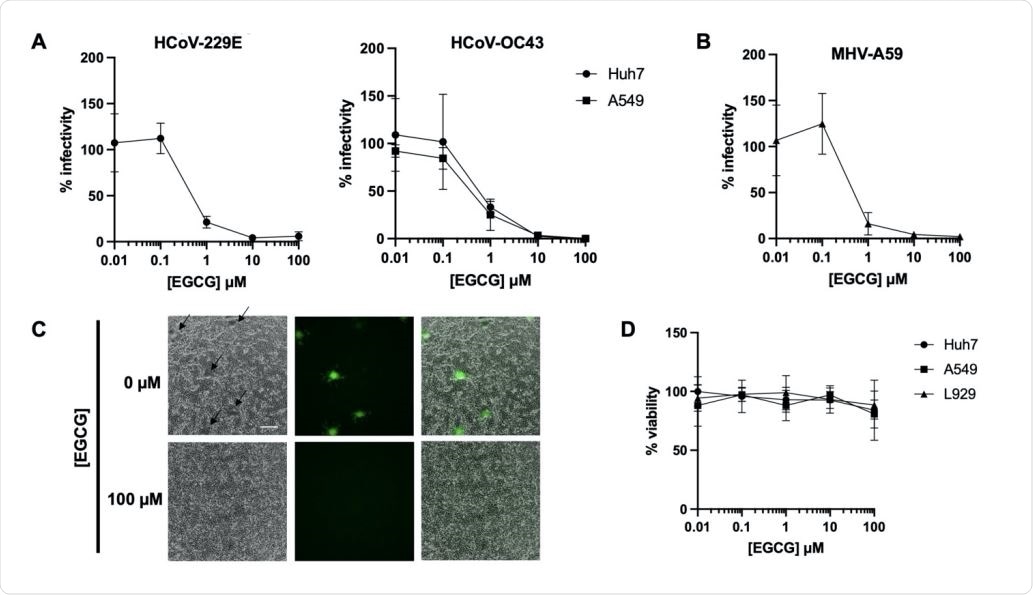

The study findings revealed that EGCG significantly inhibits cellular infection caused by human common cold coronaviruses and murine coronaviruses at sub-micromolar or low-micromolar concentrations. Moreover, EGCG was found to inhibit syncytia formation (fusion of infected cells with nearby cells to form large multi-nucleated cells). At all tested concentrations, EGCG exhibited a minimal effect on cell viability.

EGCG pre-treatment inhibits diverse CoV infections. Pre-treatment of authentic HCoV-229E and HCoV-OC43 (A) or murine coronavirus MHV-A59 (B) with EGCG for 10 min at 37°C prevented infection of Huh7, A549 or L292 cells, respectively. Mean values with standard deviation of three independent experiments are plotted. (C) A reduction in syncytia (black arrows) was observed for EGCG-treated MHV-A59. Scale bar: 200 µm. (D) Cell exposure to EGCG during the 2 h infection had minimal effect on cell viability. Mean values with standard deviation of two independent experiments with duplicates are plotted.

Pseudotyped lentiviral particles expressing spike protein of highly pathogenic human coronaviruses (SARS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and SARS-CoV-2) and a bat coronavirus were used to examine whether EGCG can prevent viral entry.

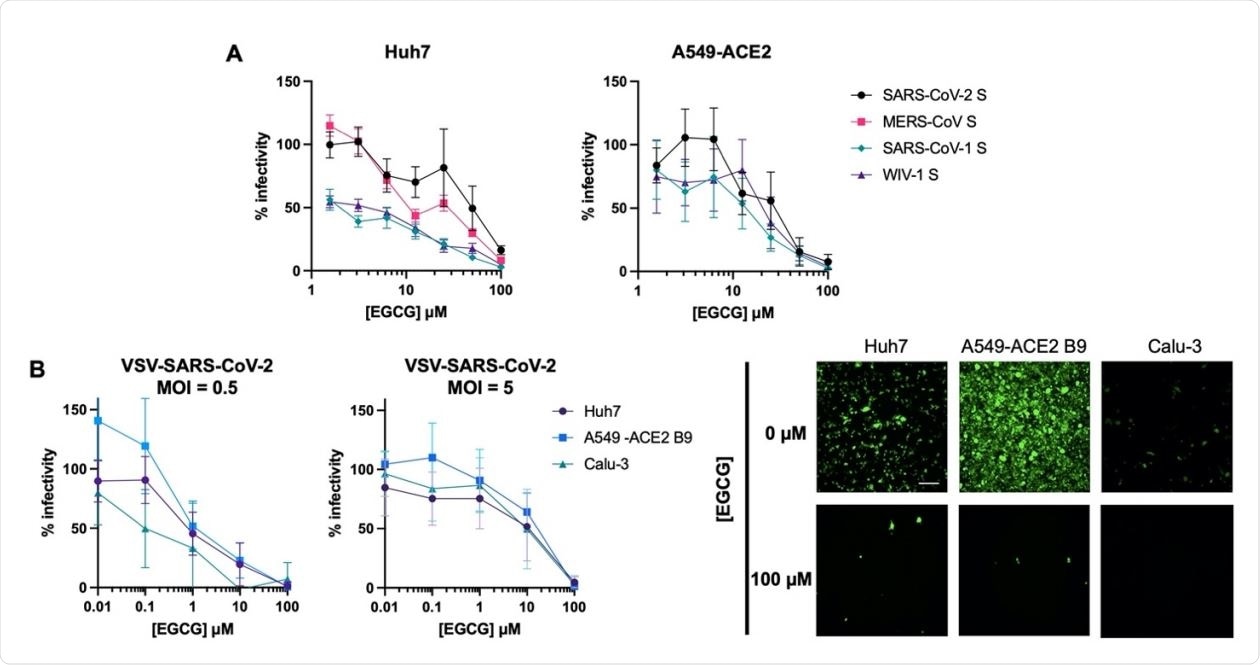

The findings revealed that EGCG efficiently inhibits host cell entry of all tested coronaviruses by blocking interaction with ACE2.

Importantly, experiments conducted using different amounts of spike-expressing vesicular stomatitis virus revealed that the antiviral activity of EGCG depends on the number of viral particles (virions) used to infect cells.

The mode of action of EGCG was determined by either treating the cells with EGCG first, followed by viral infection; or, infecting the cells first with a virus, followed by treatment with EGCG (time-of-addition experiments). However, in both conditions, EGCG failed to inhibit viral infectivity at low micromolar concentrations.

For further evaluation, binding assays were performed by infecting the cells with EGCG-pretreated viruses. In this experiment, heparin, a viral attachment inhibitor, was used as a positive control. The findings revealed that similar to heparin, EGCG potently inhibits the attachment between virus and host cell.

EGCG inhibits entry of highly pathogenic CoVs. (A) EGCG treatment reduced entry of lentiviral particles pseudotyped with S from SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, or WIV1-CoV. Mean values with standard error of the mean of three independent experiments each done in triplicates are plotted. (B) EGCG displayed MOI-dependent inhibition of VSV-SARS260 CoV-2 in Huh7, A549-ACE2 B9 and Calu-3. Mean values with standard deviation of three independent experiments each in duplicates are plotted. Representative images are shown. Scale bar: 200 µm.

Study significance

The study highlights the importance of EGCG as a pan-coronavirus entry inhibitor. Specifically, EGCG prevents rodent, bat, and human coronavirus infections primarily by inhibiting viral attachment to host cells. Furthermore, being a natural compound, EGCG exerts antiviral activity without adversely affecting cell viability.

Despite low bioavailability and stability under physiological conditions, the scientists believe that EGCG could be used as a potent antiviral compound against a broad range of human viruses, including coronaviruses.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources