Bloom’s findings are based on the identification and recovery of a dataset containing SARS-CoV-2 sequences from early on in the Wuhan epidemic that had been deleted from The National Institutes of Health’s Sequence Read Archive.

Bloom says the analysis suggests that the progenitor of known SARS-CoV-2 sequences differs from the Huanan Seafood Market sequences and is at least three mutations closer to SARS-CoV-2’s bat coronavirus relatives.

“The current study suggests that at least in one case, the trusting structures of science have been abused to obscure sequences relevant to the early spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan,” writes Bloom. “A careful re-evaluation of other archived forms of scientific communication, reporting, and data could shed additional light on the early emergence of the virus.”

A pre-print version of the research paper is available on the bioRxiv* server, while the article undergoes peer-review.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

The origin of SARS-CoV-2 remains a mystery

Understanding the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan is essential to trace the origin of the virus.

The first reports outside of China at the end of December 2019 highlighted the Huanan Seafood Market as a site of zoonotic spread.

However, this theory became increasingly unlikely as reports of earlier cases in 2019 emerged that had no connection to the market.

For example, Professor Yu Chuanhua from Wuhan University told the “Health Times” that the records he reviewed included two cases in mid-November and one suspected case on September 29th.

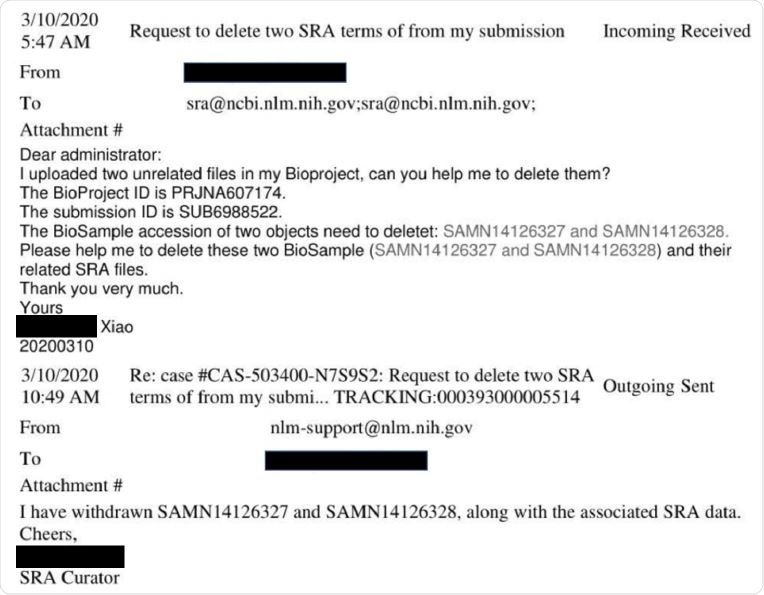

Example of the process to delete SRA data. The image shows e-mails between the lead author of the pangolin coronavirus paper Xiao et al. (2020) and SRA staff excerpted from USRTK (2020).

Chinese CDC banned the sharing of information without approval

At around the same time, the Chinese Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an order forbidding sharing information about the COVID-19 epidemic without approval. China’s State Council then issued a much broader order requiring central approval of any publication related to COVID-19.

In 2021, the joint World Health Organization (WHO)–China report dismissed all reported cases prior to December 8th 2019, as not COVID-19, and the theory that the virus may have originated at the Huanan Seafood Market was revived.

Although there is much debate surrounding how exactly SARS-CoV-2 infected the human population, it is universally accepted that the virus’s deep ancestors are bat coronaviruses.

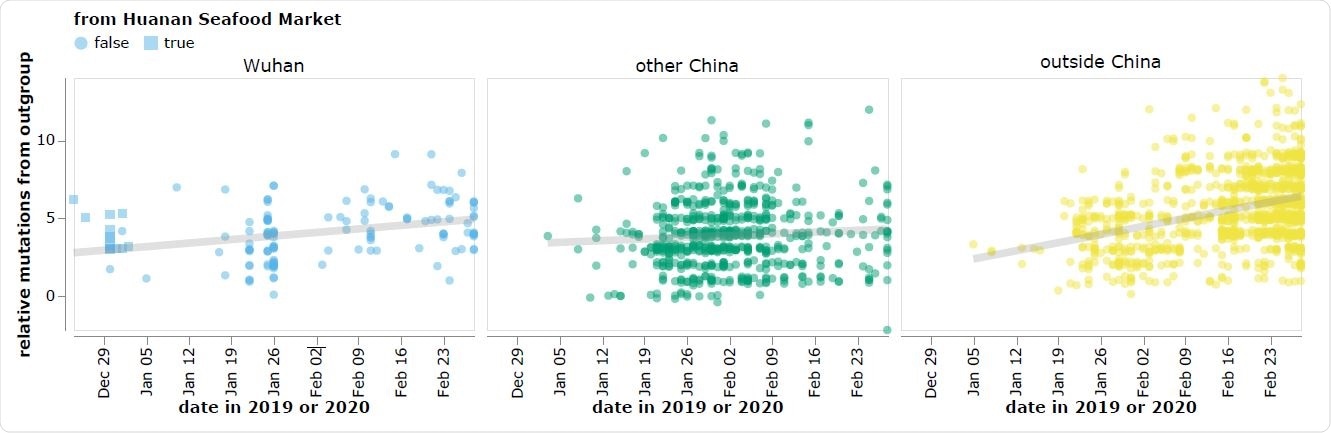

The reported collection dates of SARS-CoV-2 sequences in GISAID versus their relative mutational distances from the RaTG13 bat coronavirus outgroup. Mutational distances are relative to the putative progenitor proCoV2 inferred by Kumar et al. (2021). The plot shows sequences in GISAID collected no later than February 28, 2020. Sequences that the joint WHO-China report (WHO 2021) describes as being associated with the Wuhan Seafood Market are plotted with squares. Points are slightly jittered on the y-axis. Go to https://jbloom.github.io/SARS-CoV-2_PRJNA612766/deltadist.html for an interactive version of this plot that enables toggling of the outgroup to RpYN06 and RmYN02, mouseovers to see details for each point including strain name and mutations relative to proCoV2, and adjustment of the y-axis jittering.

However, the earliest known SARS-CoV-2 sequences, which are mostly derived from the Huanan Seafood Market, differ significantly from these bat coronaviruses, compared with other sequences collected at later dates outside of Wuhan.

“As a result, there is a direct conflict between the two major principles used to infer an outbreak’s progenitor: namely that it should be among the earliest sequences, and that it should be most closely related to deeper ancestors,” writes Bloom.

What did the current study involve?

Bloom identified a dataset of SARS-CoV-2 sequences isolated from outpatient samples collected early on in the Wuhan epidemic that had been deleted from the NIH’s Sequence Read Archive. He recovered the files from the Google Cloud and reconstructed partial sequences of 13 early epidemic viruses.

Phylogenetic analysis of these sequences, in conjunction with careful annotation of existing ones, suggested that the early Wuhan sequences from the Huanan Seafood Market that have been the focus of the joint WHO–China report are not fully representative of the viruses that were actually present in Wuhan at the time.

The RaTG13 coronavirus that infects the horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus affinis) has been identified as sharing the greatest genome sequence identity with SARS-CoV-2 to date.

However, the early Huanan Seafood Market sequences are more distant from RaTG13 than sequences collected in January from other locations in China and even other countries.

“All sequences associated with this market differ from RaTG13 by at least three more mutations than sequences subsequently collected at various other locations – a fact that is difficult to reconcile with the idea that the market was the original location of the spread of a bat coronavirus to humans,” writes Bloom.

More about the deleted sequences

Phylogenetic analysis of the deleted sequences revealed that four GISAID (Global Initiative on Sharing Avian Influenza Data) sequences collected in Guangdong that fall within a putative progenitor node were isolated from two different clusters of people who traveled to Wuhan in late December of 2019. These individuals then developed symptoms before or on the day that they returned to Guangdong, where their viruses were ultimately sequenced.

“All sequences from patients infected in Wuhan but sequenced in Guangdong are more similar to the bat coronavirus outgroup than sequences from the Huanan Seafood Market,” writes Bloom.

These deleted data as well as existing sequences from Wuhan-infected patients hospitalized in Guangdong, show that early Wuhan sequences frequently contained the T29095C mutation and were less likely to carry the mutations T8782C and C28144T than sequences in the joint WHO-China report.

Deletion of the data has important implications for future studies

Bloom says the deletion of such an informative data set has implications beyond those gleaned directly from the recovered sequences.

Firstly, samples from early outpatients in Wuhan represent a gold mine for anyone seeking to understand the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

Secondly, genomic epidemiology studies of early SARS-CoV-2 must focus on the provenance and annotation of the underlying sequences as much as they do technical considerations.

In addition, future studies should devote equal effort to going beyond the annotations in GISAID to carefully trace the location of patient infection and sample sequencing, says Bloom.

“In addition, I suggest it could be worthwhile to review e-mail records to identify other SRA [Sequence Read Archive] deletions.”

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources