The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the agent that caused the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, has affected the USA both physically and economically.

In babies, breastfeeding may be protective due to protective antibodies passed from the immune mother to the infant, conferring passive immunity.

A new study published on the medRxiv* preprint server explores the presence of immunoglobulin (Ig) antibodies IgA and IgG against SARS-CoV-2 in breast milk secreted by women with confirmed infection. The scientists also delineated the specific antigens targeted by the antibodies.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Background

Breast milk contains antibodies protective against many pathogens encountered by the mother or against which she has been vaccinated. In addition, factors like lactoferrin, a globular glycoprotein found in breast milk, have documented antimicrobial activity.

About 90% of breast milk antibodies are of the IgA class, mostly as secretory IgA (sIgA), which shields it from being broken down in the mouth and gut of the infant. Less than a tenth, and 2%, respectively, are made up of IgM and IgG antibodies, the latter being primarily transported in from serum.

Earlier studies have reported both IgA and IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in the breast milk, soon after the onset of the pandemic, directed against the viral nucleocapsid (N), spike (S) protein, and the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the spike in particular.

Such antibodies are found in over 75% of milk samples, both IgG and IgA, with the latter being at higher levels.

What did the study show?

The study included 21 women with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by the reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), mostly White, with one in seven being of other ethnicities except for Hispanic. The average age of the mother and the child was 35 years and 10 months, respectively.

About a quarter were obese, and over 40% had other health conditions such as hypertension, asthma, thyroid dysfunction, or renal impairment. All had symptomatic COVID-19, with symptoms lasting for a mean of 25 days.

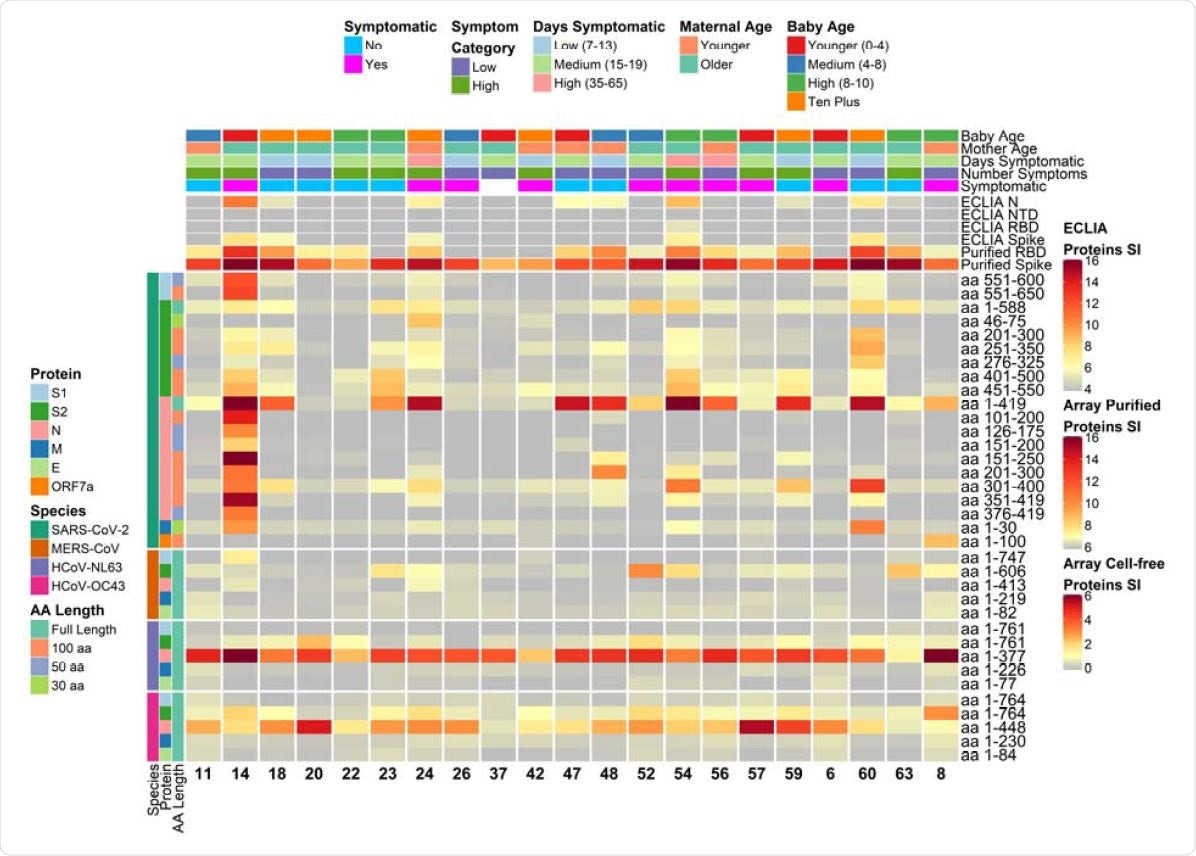

Heatmap depicting relative IgG antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 as compared to other HCoVs and clinical data. The heatmap presents the signals of antibody binding to individual proteins and protein fragments within the antigenic regions of SARS-CoV-2, as well as the full-length structural proteins of MERS-CoV, HCoV-NL63 and HCoV-OC43, for individual samples. Columns represent breast milk samples that were analyzed for IgG based on the selection of one sample per mother with maximal IgA responses. Mother IDs are indicated at the bottom of each column. Rows represent proteins or protein fragments: 20 SARS-CoV-2 proteins or fragments filtered for having a maximal normalized log2 signal intensity of at least 2.0 in one or more mother’s samples (noise levels for breast milk IgG were lower than IgA, and thus the normalized cutoff was set at 2.0 instead of 1.0 used for IgA), and five proteins each of MERS-CoV, HCoV-OC43 and HCoV-NL63. Antibody signal intensity is shown on a color scale from grey to red. Log2 signal intensities from recombinant purified proteins on the array and log2 signal intensity from proteins assayed on the ECLIA platform are overlaid above the array cell-free expressed proteins and shown with independent grey-to-red color scales. Sample clinical information is overlaid above the heatmaps and includes categories at the time of sampling for COVID-19 symptoms, number of symptoms, number of days symptomatic, maternal age and baby age. Protein/fragment information is annotated to the left of the heatmaps and includes the virus, full-length protein name and the amino acid length of the protein fragments (“AA Length”, as full length, 100, 50 or 30 aa).

IgA production in milk differs in targeted viral protein

Using the electro-chemiluminescent immunoassay (ECLIA), the scientists found that 24 viral proteins, either full-length or fragmented, reacted with breast milk IgA in one or more breast milk samples. The most commonly targeted antigens included the N and S proteins, with 9 and 5 samples reacting, respectively, to the antigens when expressed on E. coli using an in vitro transcription and translation system (IVTT).

When purified recombinant proteins were used, the ECLIA showed IgA reactivity to N and S in 19 and 18 samples, respectively. The RBD and the N-terminal domain (NTD) were reactive in 16 and 12 cases, respectively. Antigens that were reactive in only one patient included the M protein, the ORF3a and the ORF7a.

The IgG reactivity was similar but with fewer samples reactive to the N protein by ECLIA. In contrast, the same team of scientists found that most patients showed antibody production targeting the N or S proteins.

An earlier study did mirror the same findings of high N and RBD reactivity.

Specific regions of reactivity

The researchers also found that different subjects showed antibody recognition to different sites. The S1 domain’s C-terminal region was recognized in one subject only, while other subjects had milk IgA reactive to different fragments of the S2 or N proteins.

The IgG levels also varied from woman to woman, confirming similar heterogeneity in another study, which also showed that there is higher variation between breast milk samples compared to serum. In other words, the systemic response to the virus is relatively constant but not so the mucosal secretory response to the virus in breast milk.

IgA profiles show significant variation

The profiles of IgA secretion were strangely different between the lactating women. The subject showing the highest IgA levels had IgA antibodies recognizing a unique fragment of the S1 domain, as well as the highest IgA titer to the full-length N protein. It suggests an anamnestic response, perhaps contributed to by cross-reactive antibodies to human endemic seasonal coronaviruses.

Another possibility is that the patient’s breast milk antibodies were detected late in infection, and the short follow-up of only seven days may have made it impossible to tell if the IgA levels would have fallen thereafter, as seen in many other subjects.

Several others showed antibody recognition of one or more epitopes on various viral proteins, such as the N protein, but also recognized the N protein of other coronaviruses such as the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus or the hCoV OC43, which have ~40% sequence identity with the SARS-CoV-2 N.

Many other women had breast milk IgA or IgG that showed low or no responses to these antigens. Thus, more research is needed on the reasons for this variation in IgA recognition of antigenic targets.

SARS-CoV-2 antibody and risk factors

The scientists did not find any association with clinical factors, such as the presence of symptoms, or age. However, the breast milk samples were collected by symptom date, which does not always reflect the duration of exposure to the virus.

The lack of antibody recognition of the S1 protein or its fragments could be because of the absence of post-translational modifications, typical of eukaryotic cells. To overcome this, the scientists used purified recombinant spike and RBD in microarray tests and ECLIA.

Conclusions

The breast milk samples from lactating mothers with confirmed infection contained IgA that reacted to multiple SARS-CoV-2 antigens. The greatest reactivity was seen with SARS-CoV-2 N and S proteins, with 43% and 24% of women responding to one or more fragments of the N and S antigens.

“Overall, individual COVID-19 cases had diverse and unique milk IgA profiles over the course of follow-up since onset of SARS-CoV-2 symptoms.”

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Bode, L. et al. (2021). Characterization of SARS CoV-2 Antibodies in Breast Milk from 21 Women with Confirmed COVID-19 Infection. medRxiv preprint. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.19.21260661. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.07.19.21260661v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Bode, Lars, Kerri Bertrand, Julia A. Najera, Annalee Furst, Gordon Honerkamp-Smith, Adam D. Shandling, Christina D. Chambers, David Camerini, and Joseph J. Campo. 2022. “Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies in Human Milk from 21 Women with Confirmed COVID-19 Infection.” Pediatric Research, November. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-02360-w. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41390-022-02360-w.