Evidence suggests that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) can be transmitted without contact by respiratory droplets and aerosols bearing the virus when coughing, sneezing, speaking, and breathing. The virus has been cultured from aerosols collected nearby COVID-19 patients, and such aerosols can linger in still air for hours.

Some studies have suggested that emission rates of SARS-CoV-2 from infected individuals could be in the range of several million viral RNA copies per hour via breathing. However, the kinetics are challenging to determine in humans. In a research paper recently uploaded to the bioRxiv* preprint server by researchers at Virginia Tech, golden Syrian hamsters are utilized as a model to track the production of SARS-CoV-2 loaded aerosols throughout infection, as hamsters, unlike mice, are capable of asymptomatic infection and also better represent the high viral titers seen in human saliva.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

How was the study performed?

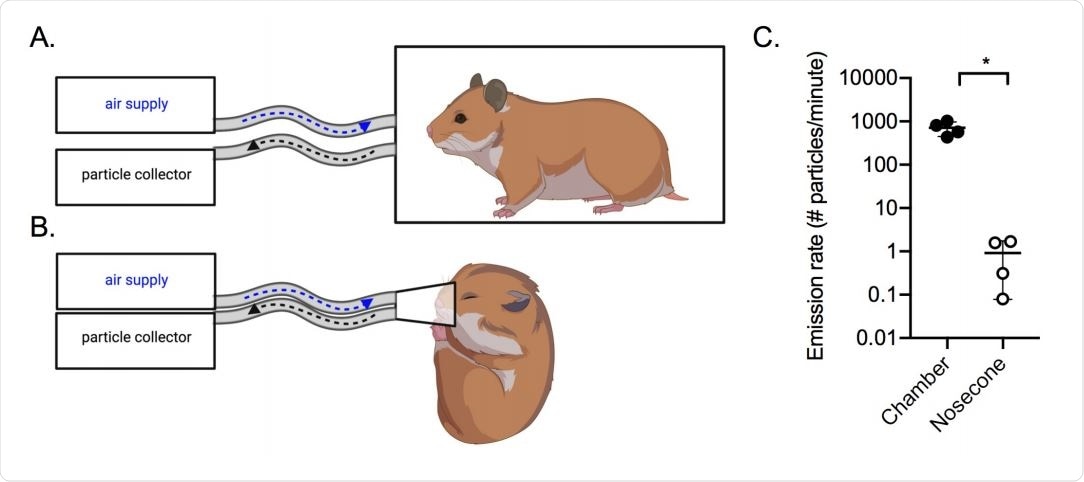

Hamsters were inoculated with wildtype SARS-CoV-2 and examined daily, with samples collected from the air, mouth, nasal cavity, fur, and rectum, and in the study's final stages, bronchial and lung tissue. The hamsters were housed within a sealed chamber to allow any aerosols to be continuously collected and analyzed.

Analysis was conducted using a particle sizer capable of detecting aerosols in the range of 0.5-20 µm, positioned by an outlet tube with a flow rate of 1 liter per minute. At the same time, fresh air was delivered via an inlet. In a second form of the experiment, hamsters were anesthetized and had a nosecone placed over the nose and mouth to capture aerosols directly.

Within the chamber, where hamsters were allowed to move freely, 700 aerosol particles per minute per hamster were collected, almost all of which were smaller than 10 µm in diameter. However, the anesthetized hamsters only generated one aerosol particle per minute per hamster, with a similar size distribution. The breathing rate of the hamsters was very low while anesthetized, potentially explaining this result.

Air sampling methods. Aerosols were collected using a condensation sampler or a 383 aerodynamic particle sizer. (A) Air was collected from awake hamsters within a sealed 2L 384 chamber; (B) Air was collected from anesthetized hamsters using a nosecone. (C) Aerosol 385 particle emission rate from uninfected hamsters (n=4) in the chamber (filled circles) or by 386 nose cone (open circles). *p<0.05.

Infectious SARS-CoV-2 can linger in aerosols

The peak viral titer within the mouth and nose of the hamsters were recorded on the first and second days post-infection, respectively. Viral titers after that declined over time. Infectious virus was detected in the aerosols collected from the hamsters on the first and second days only, with viral loads below the plaque assay limit. Viral RNA was also tracked in the air using real-time PCR, which is much more sensitive, though it cannot confirm that the virus in the aerosol is infectious. High viral RNA loads were detected in aerosols during ten days post-infection, with highs correlating with the plaque assay tests, peaking in the first few days.

Interestingly, significantly higher viral loads were found within the aerosols of male hamsters than female hamsters by plaque assay, though differences were negligible by RT-PCR. Females also had a delayed peak of the highest viral load. It has yet to be determined if this result applies to humans, though some sex differences have been observed during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Possibly, the female hamsters emitted a higher rate of defective viral particles, explaining the almost identical viral RNA loads detected with differing infectious particle numbers.

Very high viral loads were detected within the inoculated hamsters' mouth, nose, and lungs, with some also detected on the fur and rectum, suggesting that infectious aerosol particles had landed on the fur and lingered. Alternatively, the viral aerosols may also have been resuspended into the air from fur, providing further means of non-contact transmission. A restrictor was also placed on the air intake to limit the maximum size of aerosols to 8 µm, and the group found no significant difference in average titer, implying that most infectious particles are below this size.

Several public health agencies have begun listing SARS-CoV-2 as an airborne virus, which infers that the virus may remain airborne for more extended periods and significantly over greater distances than previously hypothesized. The evidence of this study supports the categorization of SARS-CoV-2 as an airborne virus, the implications of which include the importance of ventilation as a preventative measure against COVID-19.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources