The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic spread rapidly across the globe, causing a worldwide health crisis and economic collapse.

As nations begin to recover, researchers from the National Taiwan University and Academia Sinica in Taipei have been looking to identify the changes the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) underwent over the course of the pandemic in order to better understand why the disease showed such virulence.

Other coronaviruses have not caused such widespread effect; while there was global worry over both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, neither showed transmission rates as high as COVID-19. The other four coronaviruses that can infect humans only cause mild symptoms.

A preprint version of the group’s study is available on the bioRxiv* server, while the article undergoes peer review.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

The spike protein is key to the pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 and the earlier SARS-CoV - the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the S1 subunit binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which allows viral entry. At the same time, the N-terminal of the spike protein allows for membrane fusion.

Targeting the RBD is most common for vaccines, as it allows neutralizing antibodies to not only target the disease but also prevent it from entering cells. Antibodies generated from natural immunity will normally target these areas of the spike protein, or the nucleocapsid or envelope proteins. The reason vaccines rarely target the N-terminal domain is due to the rapid adaptions seen between variants - antibodies effective against the N-terminal domain of the original strain found in Wuhan, China, mostly lose functionality against the Delta strain.

It is widely thought that SARS-CoV-2 may be zoonotic in nature due to the high similarity from a coronavirus found in bats in the Yunnan Province of China. It is also known that the disease can infect several other species, including hamsters and mice.

Multiple mutations are necessary for such a virus to have such high transmission across several species, each capable of conferring an evolutionary advantage. In both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, these adaptations can clearly be seen in incremental stages prior to developing infectivity in humans. A vast majority of the adaptions seen in the initial SARS-CoV epidemic were seen in the spike protein. Analysis of MERS-CoV sequences revealed the same.

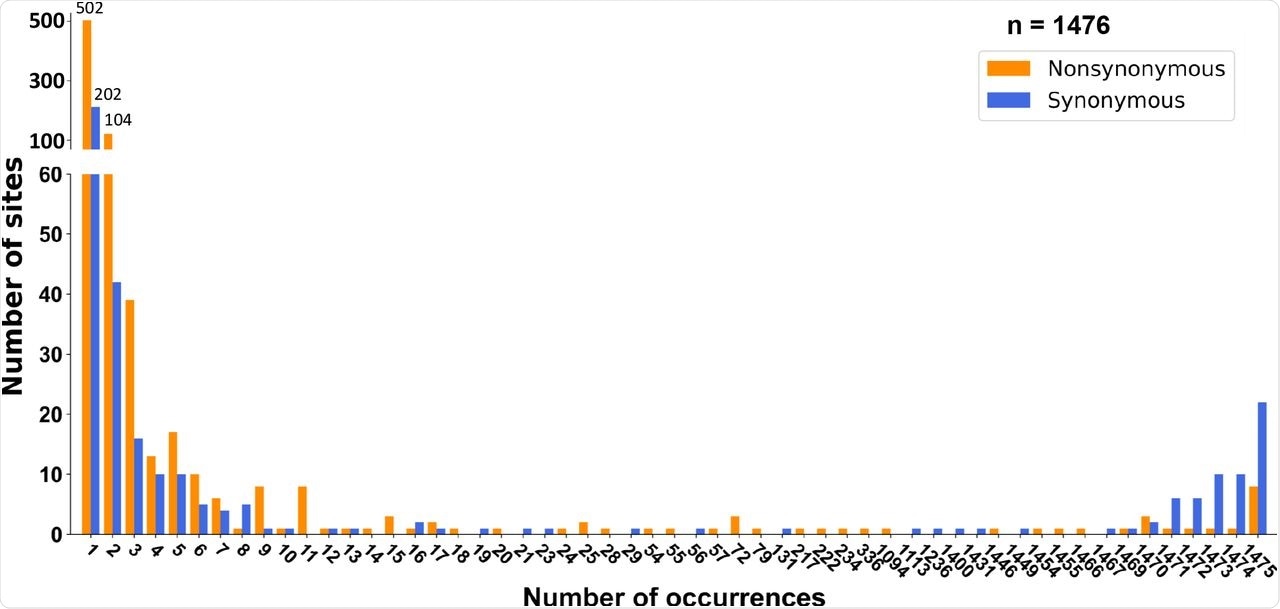

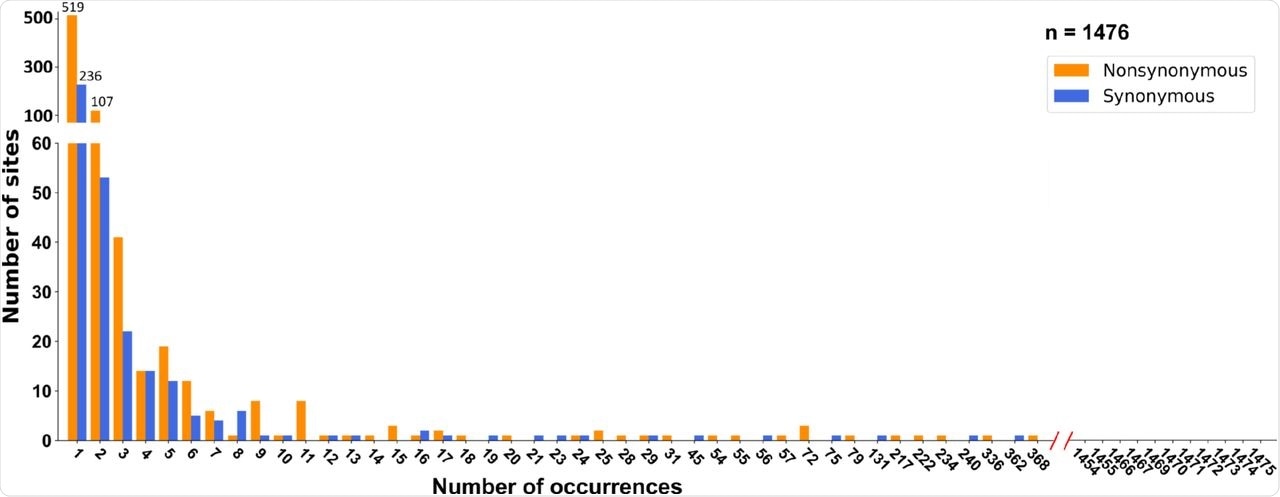

Site frequency spectra of SARS-CoV-2 during the early epidemic (2019/12-2020/2) in humans. (a) Site frequency spectra (SFSs) were inferred using RaTG13 as the outgroup. Significant deviation from neutral expectation under exponential population growth was found in both synonymous (p < 10-5) and nonsynonymous mutations (p < 10-5).

Unlike the previous two coronaviruses that caused severe disease in humans, SARS-CoV-2 does not show adaptive evolution but rather evolves through neutral or purifying selection - with several key exceptions, such as the D614G mutation that increases transmissibility, and the G142D and T951 mutations that help evade the host immune response.

Almost all mutations that affected SARS-CoV-2 transmissibility and immune evasion were spike protein mutations. The authors theorize the lack of adaptive mutations in SARS-CoV-2 is due to either a unique feature present within the disease or the pre-pandemic spread of a less pathogenic strain of SARS-CoV-2. To test these theories, they examined the spread of coronavirus in mink and analyzed nearly 28,000 genomes of SARS-CoV-2. If SARS-CoV-2 was adapted to cross-species transmission, no positive selection should be seen. If SARS-CoV-2 experienced adaptive evolution after crossing to humans, accelerated adaption should also be seen in minks.

(b) SFSs cross-referenced by the phylogeny and date of sampling (see main text for details). Neither synonymous nor nonsynonymous mutations deviate from the neutral expectation.

By aligning the sequences against a reference genome and constructing phylogenies, they could estimate the number of changes per site and examine the data for signatures of positive selection. It appeared that while transmission between humans and minks occurred multiple times, the vast majority of these events did not cause large-scale infection of minks with SARS-CoV-2. However, several newly emerged strains from the Netherlands showed clear-lasting infection and transmission, suggesting that the strain acquired novel mutations that allowed it to sustain pathogenicity in the new host. The spread of mutations also showed a clear pattern showing strong evidence of positive selection during the early epidemic, likely indicating that the virus circulated in humans prior to widespread notice of the pandemic.

The authors emphasize the importance of their study in highlighting the significance of the site of the outbreak as compared to the location of initial infection - as zoonotic diseases may circulate in humans before becoming dangerous, those local to the area where the disease initially jumped species may have some in-built immunity that could provide enough herd immunity to prevent further spread.

They also suggest that it is likely many of these zoonotic events occur - but with the wrong conditions, such as large populations of wild animals mixed with a mobile and crowded human population, the risk of those events escalating into a pandemic is far greater.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Tai, J., 2021. Signatures of adaptive evolution during human to mink SARS CoV2 cross-species transmission inform estimates of the COVID19 pandemic timing, bioRxiv, preprint server. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.15.459215, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.09.15.459215v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Tai, Jui-Hung, Hsiao-Yu Sun, Yi-Cheng Tseng, Guanghao Li, Sui-Yuan Chang, Shiou-Hwei Yeh, Pei-Jer Chen, Shu-Miaw Chaw, and Hurng-Yi Wang. 2022. “Contrasting Patterns in the Early Stage of SARS-CoV-2 Evolution between Humans and Minks.” Molecular Biology and Evolution 39 (9). https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msac156. https://academic.oup.com/mbe/article/39/9/msac156/6658056.