Researchers in the United States have conducted comprehensive profiling of humoral immune responses in pregnant, lactating, and non-pregnant women following coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccination to probe differences in vaccine-induced immunity.

The team from Harvard University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the University of Pennsylvania, in their recent research published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, have reported distinct response profiles across each of these immunological states, suggesting that vaccines may drive different antibody functional profiles, programmed evolutionarily to maximize protection for the mother-baby dyad in that unique immune state.

Immunological adaptations occur throughout pregnancy and lactation

Pregnant women undergo substantial immunological changes to render immunological tolerance to the fetus and allow fetal growth without rejection. Other adaptations also occur, allowing the maternal immune system to continue to protect the mother-infant dyad against infections during pregnancy and after delivery through lactation.

Physiological and hormonal changes, along with this delicate balance of tolerance and immunity, contribute to increased susceptibility to some infections in pregnancy, including more severe COVID-19.

Antibodies, in addition to their role in neutralization, contribute to protection against COVID-19 through their ability to recruit the innate immune response with their Fc-domain, which is associated with protection from infection following vaccination, play a critical role in antibody transfer across the placenta, and may also influence transfer into breastmilk.

While reports have shown the immunogenic potential of vaccines in pregnant and lactating women, none have characterized the Fc-profile of vaccine-induced antibodies in pregnant and lactating women.

Therefore, it is critical to understand how pregnancy and lactation affect immune responses, including Fc immune profile, to vaccination, impacting antibody transit across the placenta or into breastmilk to guide the vaccine recommendations for this vulnerable population.

Cohort study on pregnant, lactating, and non-pregnant controls vaccinated with mRNA vaccines

The team evaluated the SARS-CoV-2 humoral immune responses in a cohort of 84 pregnant, 31 lactating and 16 non-pregnant age-matched controls vaccinated with either BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273 vaccine.

Serological and functional assays were performed on samples collected after the first dose (post-prime, at the time of the second dose), after the second dose (post-boost, 2-5.5 weeks following the second dose), and at delivery (for pregnant participants).

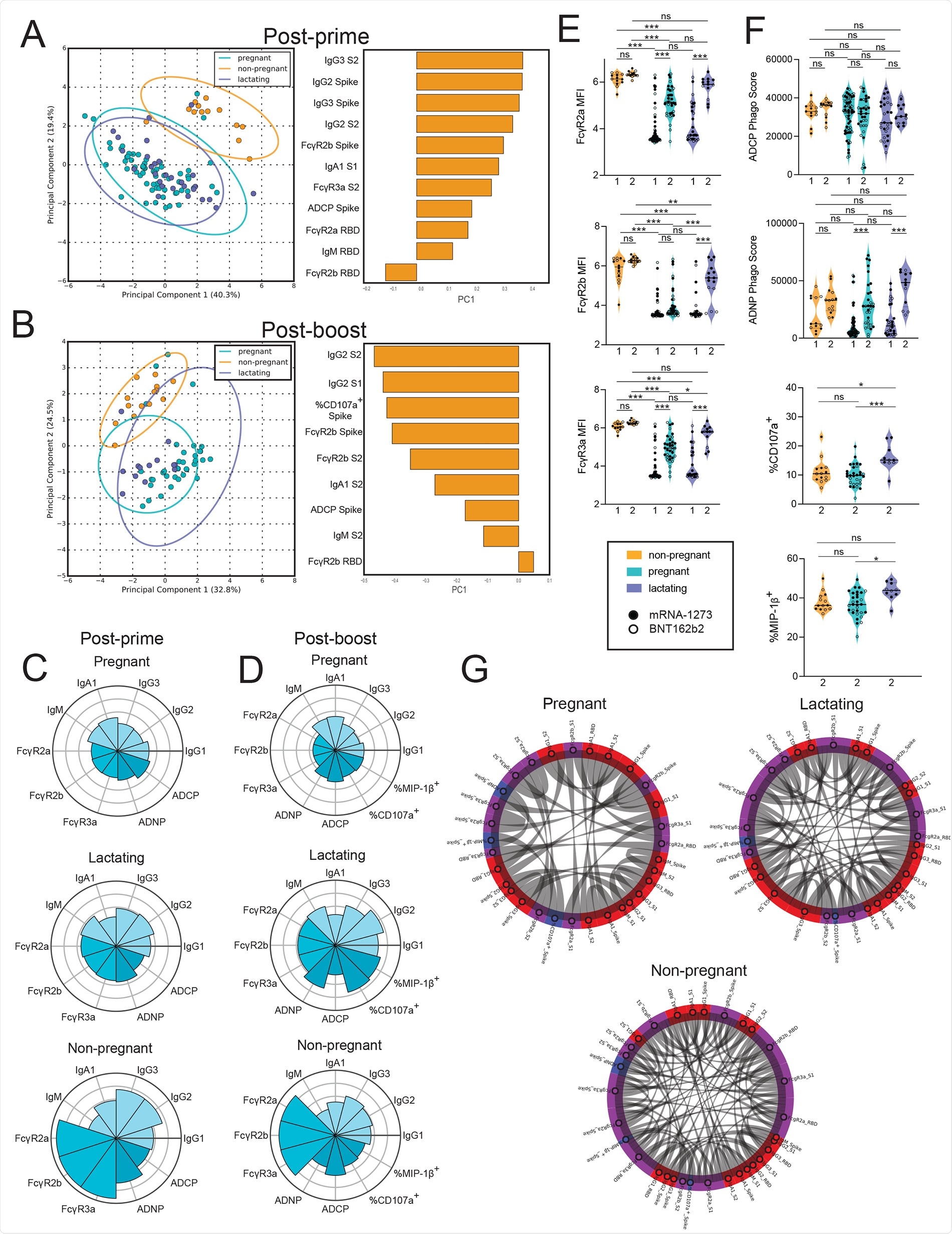

Vaccination induces enhanced FcR-binding in non-pregnant women.A and B. A principal component analysis (PCA) was built using LASSO-selected antibody features at 3 to 4 weeks post prime vaccination (A) or 2 to 5.5 weeks post boost vaccination (B). The dot plots show the scores of each individual, with each dot representing an individual. The ellipses represent the 95% confidence interval for each group. The bar plots show the loadings of the LASSO-selected features along principal component 1 (PC1). C and D. The polar plots show the mean percentile rank for each feature for post-prime (C) and post-boost (D) samples. Features were ranked separately for each time point. E. The violin plots show the FcγR-binding for non-pregnant, pregnant, and lactating women at post-prime (1) (non-pregnant n = 13, pregnant n = 64, lactating n = 28) and post-boost (2) (non-pregnant n = 14, pregnant n = 36, lactating n = 13). The filled dots show the titer for women who received mRNA-1273, and outlines show the titer for women who received BNT162b2. MFI, median fluorescence intensity. Data are presented as median ± IQR. Significance was determined by a one-way ANOVA followed by posthoc Tukey’s multiple comparison test. P-values were then corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bejamini-Hochberg procedure, * p <0.05, ** p < 0.01,*** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, ns, not significant. F. The violin plots show the antibody functions for non-pregnant, pregnant, and lactating women at post-prime (1) (non-pregnant n = 13, pregnant n = 64, lactating n = 28) and post-boost (2) (non-pregnant n = 14, pregnant n = 36, lactating n = 13). The filled dots show the titer for women who received mRNA-1273, and outlines show the titer for women who received BNT162b2 vaccine. Phago indicates phagocytosis. Data are presented as median ± IQR. Significance was determined by a one-way ANOVA followed by posthoc Tukey’s multiple comparison test. P-values were then corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bejamini-Hochberg procedure, * p <0.05, ** p < 0.01,*** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001, ns, not significant. G. The chord diagrams connect the features that have a spearman correlation > 0.75 and Bonferroni-corrected p-value < 0.05 for non-pregnant, pregnant, and lactating women. Red indicates antibody isotype, purple indicates FcR-binding and blue indicates antibody function.

Pregnant, lactating, and non-pregnant women show differential immune profiles post-vaccination

In post-prime serum samples, the team observed lower antibody and FcR-binding capacity among pregnant and lactating women compared to non-pregnant controls. Non-pregnant women had higher IgG subclass responses, higher antibody functions, and higher FcR-binding compared to pregnant and lactating women.

Post-boost samples presented lesser differences between pregnant or lactating and non-pregnant women. However, persisting differences were nearly exclusively linked to enhanced FcR-binding in non-pregnant women.

“Fc receptor (FcR)-binding and antibody effector functions were induced with delayed kinetics in both pregnant and lactating women compared to non-pregnant women after the first vaccine dose, which normalized after the second dose”, observed the team.

Noticeably, lactating women boosted their antibody response more effectively than pregnant women, marked by higher IgG titers and higher natural killer (NK) cell activity, in post-boost samples, suggesting lactating women make qualitatively different responses to the second dose of vaccine compared to pregnant individuals.

Both pregnant and lactating women raised FcR-binding serum antibodies after the second dose. Nevertheless, all FcR-binding antibodies in pregnant women and FcγR2b-binding antibodies in lactating women remained lower as compared to the non-pregnant women. The team suggests that these higher FcR-binding profiles in lactating and non-pregnant women could be linked to enhanced coordination in the humoral immune responses compared to pregnant women.

All three populations induced similar antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) and did not increase ADCP function post-boost vaccination. In contrast, antibody-dependent neutrophil phagocytosis (ADNP) activity was increased in pregnant and lactating women after boosting.

Overall, these data point to restriction in the ability of pregnant women to generate functional, but not total, antibodies with boosting compared to lactating women. Further, these data suggest that pregnant and lactating women show potential early alterations in vaccine-induced immune responses that improve after a booster vaccine.

Humoral profiles vary between maternal serum and umbilical cord blood

Maternal blood had a higher titer of antibodies compared to cord blood. Variable patterns of transfer of IgG titer, FcR-binding and antibody function were observed from the mother to the cord. Despite the recency of vaccination, equivalent, IgG1 spike protein-specific titers were transferred across the placenta to the infant.

Stable phagocytic antibodies but decreased NK-cell activating antibodies were transferred to infants. However, despite the lower titers of antibodies in the cord, the placenta was able to select for FcγR3a-binding, functionally enhanced vaccine-induced antibodies.

Boosting enhances transfer of FcR-binding IgG antibodies in breastmilk

Lactating mother serum had a preferential boosting of FcR-binding IgG responses after a booster vaccine dose. The team observed the transfer of a similar profile to the breastmilk, with high IgG antibodies and high FcR-binding capabilities post-boost.

“Vaccination appears to augment highly functional IgG transit to the milk that is likely key to antiviral immunity across viral pathogens,” the team highlights.

NK-cell activating antibodies had a low transfer ratio at the post-boost timepoint, suggesting a sieve at the mammary gland, preventing the transfer of highly inflammatory antibodies through breastmilk.

mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 vaccination induce differential antibody responses in pregnant and lactating women.

mRNA-1273 vaccinated women exhibited more focused coordination in the humoral immune response, centered around a high IgG1/IgG3 response with robust FcR-binding and functional coordination. Conversely, women receiving BNT162b2 generated a broader coordinated immune response, including IgG2 and IgM responses and the exclusion of monocyte phagocytosis (ADCP), suggesting a more diffuse overall humoral immune coordination profile.

These serum differences translated to differences in antibodies transferred in breastmilk. In addition, the team observed differences in the overall antibody profile across women receiving mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2.

Thus, as per the team’s speculation, the extra week prior to mRNA-1273 boosting may provide the time needed for the humoral immune response to mature, resulting in more functional antibody profiles.

These findings collectively point to an extended window of vulnerability in pregnancy and lactation following vaccination, requiring timely boosting to achieve fully-functional antibodies that can protect pregnant individual and their infant.