This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

By November 2021, Israel had successfully vaccinated about 80% of its population with two coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine doses. Subsequently, in June 2021, community transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus responsible for COVID-19, ceased briefly, following which the Delta variant caused the largest COVID-19-induced epidemic in the country.

Experimental data comparing the impact of three versus two vaccine doses provide evidence of the effectiveness of booster vaccine doses against symptomatic infection with the Delta variant.

About the study

In the current study, the researchers performed a prospective serosurveillance of HCWs from Ziv Medical Center (ZMC), Israel who consented to participate in the study. The researchers measured the geometric mean concentration (GMC) of circulating IgGs of participating HCWs before vaccination and at six subsequent timepoints from dose 1. These time points included:

- t1: 21 days (range 15-35 days)

- t2: 51 days (range 41-65 days)

- t3: 100-150 days

- t4: 151-210 days

- t5: 211-270 days

- t6: 271-310 days.

The researchers also evaluated trends in SARS-CoV-2 humoral immunity by age, ethnicity, vaccination, infection status, the time elapsed between priming and boosting, and other predictors. They presented the observed trends compared with anamnestic responses resulting from the third vaccine dose to those resulting from breakthrough infection.

A total of 985 vaccinated HCWs consented to participate in the current study. Of these, 86, 141, and 758 HCWs received single, two, and three vaccine doses, respectively.

The median time between the first and second and second and third was 21 days and 223 days, respectively. HCWs who received a single priming dose due to prior infection and a second dose after six months of the first dose were considered boosted.

Study findings

IgG titers gradually decreased in all age groups after six months of receiving the second vaccine dose. As compared to HCWs who were never infected with SARS-CoV-2, younger or previously infected HCWs had almost 13-fold higher IgG levels at t1 and 1.9-fold higher at t4; however, these dropped to levels less than twice as high as those never infected in 6-7 months.

Among HCWs who were never infected with SARS-CoV-2, a higher GMC was associated with younger age at t1, whereas the difference in GMC was barely significant by t5, which was 7-9 months following the first dose but before the third dose.

IgG GMC in those boosted 6-7 months after the second dose was lower than those boosted 8-9 months after the first dose. There was no association between GMC and ethnicity following a single dose of vaccine and even after subsequent doses.

The mean age of the 40 individuals who experienced breakthrough infections was 39 years, which was comparable to the mean age of 45 years in HCWs with no prior history of COVID-19. Notably, the IgG GMC before reinfection was not different from those who remained uninfected at the same time point.

Of the 899 HCW who received more than two vaccine doses, 4.4% were infected with SARS-CoV-2 between 30 days after receiving the second dose and before the third dose. This suggests that the proportion of reinfections among individuals infected prior to vaccination was comparable to the proportions of breakthrough infections among individuals who were never infected with SARS-CoV-2 and had received two vaccine doses.

Of the 302 never-infected HCWs, those who received a third vaccine dose showed a GMC of 2,618 at t6, which was 1-2 months after receiving their third dose. Comparatively, in the 21 non-boosted HCWs with a prior history of COVID-19, their GMC was significantly higher after the second.

Booster doses increased IgG levels by 18-fold or more in all age groups among those never infected. GMC in those boosted 6-7 months after the second dose was 1,999 and those boosted 8-9 months after the second dose was 2,736.

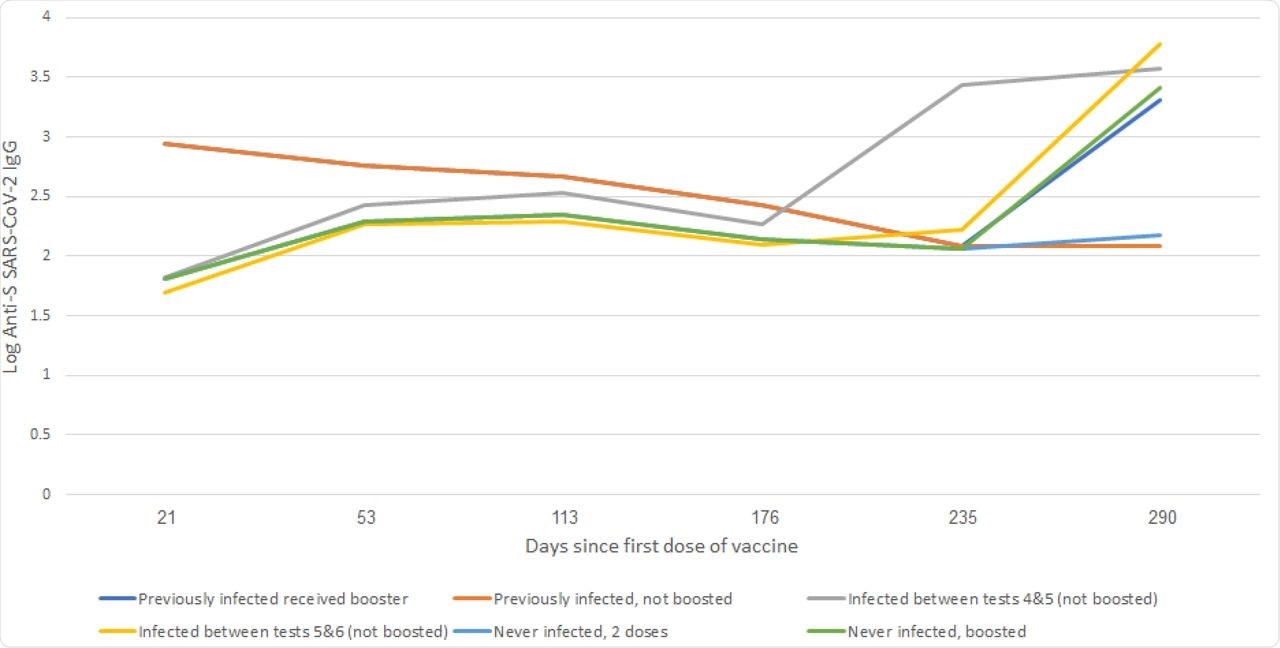

Anti SARS-CoV-2 S IgG Geometric mean concentration (log) according to infection status, Israel, January-October 2021.

Anti SARS-CoV-2 S IgG Geometric mean concentration (log) according to infection status, Israel, January-October 2021.

Conclusions

The study presented serological responses in vaccinated individuals over time. However, according to the authors, circulating IgG levels or these serological responses are not a robust predictor of protection against COVID-19 following vaccination or infection. Other methodologies to measure immunity, such as functional assays or B-cell and T-cell assays, are required.

The current study results observed that immunity wanes after six months of post-priming in all age groups, even in previously infected individuals. It also highlighted that individuals with hybrid immunity, which is defined as immunity induced by infection and vaccination, require further boosting, as boosting reverses the phenomenon of immunity waning and gives optimal protection to all age groups.

According to the result of the current study, late boosting was associated with higher IgG levels; however, booster doses given six months after the second vaccine dose triggered an anamnestic response. Hence, the study findings call for further in-depth analysis of how IgG levels correlate with protection to develop optimal boosting schedules, especially for third dose regimens.

These measures are warranted, especially amid the emergence of new variant-induced COVID-19 infections that cannot be effectively controlled with a single booster.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Edelstein, M., Beiruti, K. W., Ben-Amram, H., et al. (2021). Antibody-mediated Immunogenicity against SARS-CoV-2 following priming, boosting and hybrid immunity: insights from 11 months of follow-up of a healthcare worker cohort in Israel, December 2020-October 2021. medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2021.12.15.21267793. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.12.15.21267793v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Edelstein, Michael, Karine Wiegler Beiruti, Hila Ben-Amram, Naor Bar-Zeev, Christian Sussan, Hani Asulin, David Strauss, Younes Bathish, Salman Zarka, and Kamal Abu Jabal. 2022. “Antibody-Mediated Immunogenicity against Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Following Priming, Boosting, and Hybrid Immunity: Insights from 11 Months of Follow-up of a Healthcare Worker Cohort in Israel, December 2020–October 2021.” Clinical Infectious Diseases 75 (1): e572–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac212. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/75/1/e572/6547893.