Coronaviruses are enclosed, single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) viruses that infect vertebrates. Infection with human coronaviruses (HCoVs) results in mild to severe respiratory illness in humans.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Prior to December 2019, two of the six recognized HCoV infections included the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), both of which caused severe respiratory illness epidemics with extremely high fatality rates.

In December 2019, Wuhan, China reported an upsurge in instances of severe respiratory disease. The virus responsible for the disease was identified as SARS-CoV-2, and the disease was designated as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). By March 2020, COVID-19 had spread to nearly every country on Earth, establishing a global pandemic.

Background

Each year, around two million patients are diagnosed with lung cancer, thereby allowing this type of cancer to be the primary cause of cancer-related death. The median age of diagnosis of lung cancer is 70 years.

Non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) accounts for 84% of all lung cancer diagnoses. Immune dysregulation is a typical occurrence in cancer patients as a result of tumor malignancy and immunomodulatory therapy.

It is therefore critical to assess the efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 immunization in lung cancer patients. A recent study in thoracic cancer patients who received the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccine demonstrated that the vaccine is highly effective at eliciting protective antibody responses in these patients.

In November 2021, the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant was detected in South Africa. It has since spread to other nations and has become the dominant SARS-CoV-2 strain worldwide.

In healthy individuals, the Omicron variant is immune to both vaccine-induced and therapeutic antibodies; however, it appears to be neutralized by a booster dose-induced antibody response.

In a recent study posted to the medRxiv* preprint server, researchers from various multinational institutions examine the efficacy of mRNA vaccination in NSCLC patients to develop neutralizing antibodies against the rapidly emerging SARS CoV-2 B.1.1.529 Omicron and previously dominant B.1.617.2 (Delta) variants.

About the study

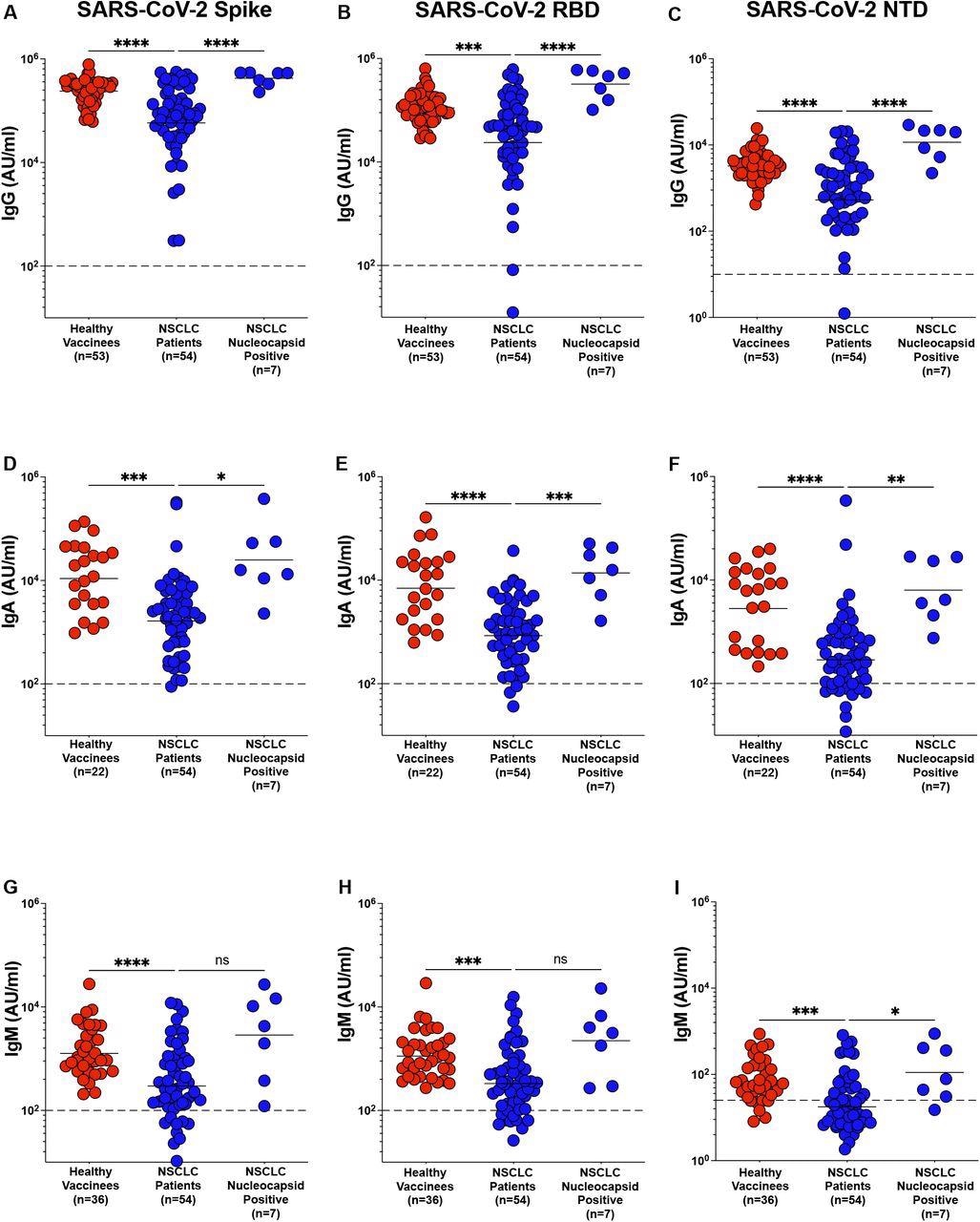

Most NSCLC patients demonstrated a robust binding immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgA, and IgM response to the mRNA vaccines one month following the second dosage. However, when compared to healthy controls, spike, receptor-binding domain (RBD), and N-terminal domain (NTD)-specific IgG titers were significantly lower.

Due to the absence of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid in the mRNA vaccine, patients with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection were identified by the presence of a high anti-nucleocapsid titer (N+) in their plasma. As compared to SARS-CoV-2 naive NSCLC patients, N+ patients showed significantly greater levels of the spike, RBD, and NTD-specific antibodies.

The authors also measured vaccine-specific IgA titers in the plasma of NSCLC patients. As with the IgG titers, vaccine-specific IgA titers were significantly lower in NSCLC patients than in healthy controls. N+ individuals had significantly higher IgA titers than SARS-CoV-2-naive NSCLC patients.

Antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine in NSCLC patients. Figure 1 A – I. Spike, RBD and NTD specific IgG (Figure 1A-C), IgA (Figure 1D-F1) and IgM (Figure 1G-I), titers in plasma from healthy vaccinees, NSCLC patients and NSCLC patients with prior exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection was measured within two months after the second dose of mRNA vaccination. Pre-pandemic plasma samples from healthy individuals were used to set the detection limit for IgG, IgA and IgM titers. Statistical differences were measured using a one-way anova. Graph shows the mean and s.e.m. ns not significant, *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001, ****p≤0.0001.

As with IgG and IgA titers, vaccine-specific IgM titers were shown to be lower in the plasma of NSCLC patients as compared to healthy persons. The authors observed no statistically significant difference in spike and RBD-specific IgM titers between N+ NSCLC patients and SARS-CoV-2 naive patients. NTD-specific IgM levels were significantly greater in N+ patients as compared to SARS-CoV-2 naive NSCLC patients.

Neutralizing antibody titers were also considerably lower in the plasma of NSCLC patients than in healthy individuals who received the vaccine. While the majority of individuals with NSCLC had neutralizing antibodies, a subgroup of these patients was unable to neutralize the live virus. The correlation between the focus reduction neutralization test (FRNT50) for live viruses and the binding spike antibody titer was found.

The authors identified a correlation between the FRNT50 and RBD-specific IgG titers in NSCLC patients. Taken together, these data suggest that most NSCLC patients develop detectable neutralizing antibody titers in response to vaccination, albeit at lower levels than healthy vaccinees. However, a significant proportion of patients with NSCLC did not produce a detectable neutralizing antibody response.

To assess the persistence of vaccine-specific antibody responses, the authors assessed the binding antibody response to mRNA vaccinations in NSCLC patients over a six-month period. After a week following the second vaccine dosage, anti-spike and anti-RBD IgG titers peaked.

Both anti-spike and anti-RBD IgG titers decreased around three months following the second dose, although this was not statistically significant. However, six months after the second dose of immunization, both anti-spike and anti-RBD-specific binding antibody responses were significantly lower than their respective peak IgG titers.

Implications

The SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant is highly effective at evading vaccine-induced neutralization in healthy persons. This could pose a significant issue for cancer patients, who have considerably lower neutralizing antibody titers against the wild-type SARS-CoV-2 strain as compared to otherwise healthy individuals.

The data in this study indicate that sera from NSCLC patients who received two doses of the mRNA vaccine exhibited significantly lowered neutralization of the Omicron variation, thereby implying that cancer patients may be more susceptible to infection with the Omicron variant than healthy vaccinated persons.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Valanparambil, R. M., Carlisle, J., Linderman, S. L., et al. (2021). Antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine in lung cancer patients: Reactivity to vaccine antigen and variants of concern. medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2022.01.03.22268599. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.01.03.22268599v2.

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Valanparambil, Rajesh M., Jennifer Carlisle, Susanne L. Linderman, Akil Akthar, Ralph Linwood Millett, Lilin Lai, Andres Chang, et al. 2022. “Antibody Response to COVID-19 MRNA Vaccine in Patients with Lung Cancer after Primary Immunization and Booster: Reactivity to the SARS-CoV-2 WT Virus and Omicron Variant.” Journal of Clinical Oncology 40 (33): 3808–16. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.21.02986. https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.21.02986.