This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Lipid nanoparticle mRNA vaccines developed against SARS-CoV-2 contain PEG-lipid conjugate in small amounts to stabilize the lipid nanoparticle. The Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 and Moderna mRNA-1273 mRNA vaccines contain about 1.95 µg and 6.01 µg of the PEG-lipid conjugates ALC-0159 and PEG2000-DMG per dose, respectively.

Although hundreds of millions of people worldwide have received lipid nanoparticle SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines containing PEG-lipids, it is not clear if anti-PEG antibodies are induced by intramuscular lipid nanoparticle mRNA vaccination and whether they impact vaccine responses.

About the study

In the present study, the researchers analyzed plasma samples taken from 55 people receiving the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine for the presence of PEG-specific antibodies. They studied serial blood samples from participants across three cohorts receiving two doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to quantify PEG-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM antibodies in response to a 40 kilodalton (kD) PEG molecule.

As a control group, the team studied plasma samples from 55 unvaccinated individuals in two separate cohorts, which included 40 SARS-CoV-2 convalescent and 15 healthy individuals, over a six-month time period.

Study findings

The results show that detectable levels of PEG-specific IgG were present before vaccination in 73% of the 55 study subjects, with titers ranging from 1:12-1:3000. Notably, 47% of the vaccinated participants had an IgG titer greater than 1:80.

An increase in PEG-specific IgG titers was seen in 67% of participants following vaccination, especially in the 35 subjects who had pre-existing antibodies. Forty-one subjects had an increase in PEG-specific IgM after vaccination, including 11 subjects who did not have PEG-specific IgG responses.

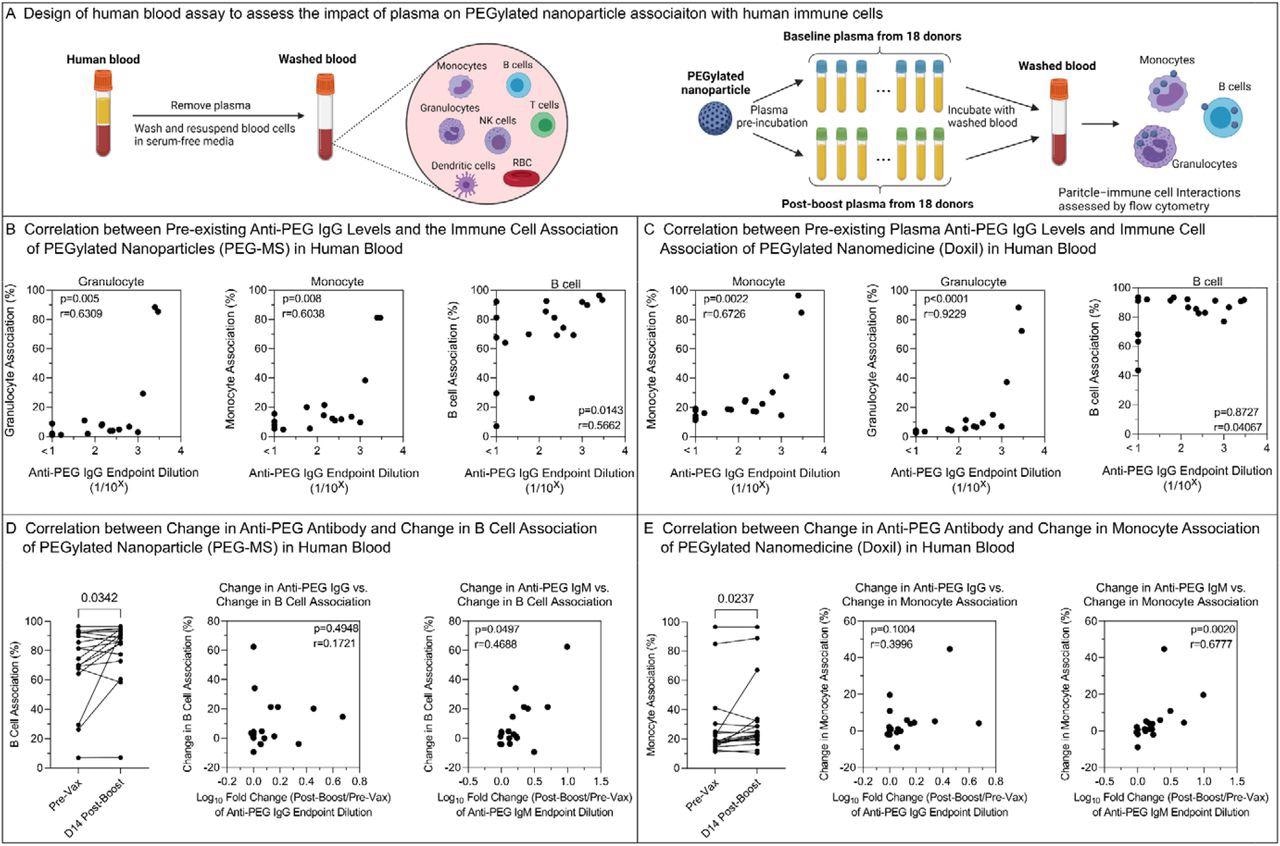

The impact of PEG-specific antibody in plasma on human blood immune cell association of PEGylated nanoparticles. A) Design of human blood assay to assess the impact of plasma on PEGylated nanoparticle association with human immune cells. Fresh human blood from a healthy donor was washed by centrifugation with serum-free media multiple times to completely remove plasma. PEGylated nanoparticles were pre-incubated with plasma from 18 donors across Cohort 1 before and day 14 post-boost of Comirnaty vaccination and then incubated with washed blood in serum-free media for 1 h at 37 °C, followed by phenotyping cells with antibody cocktails and analysis by flow cytometry. Created with BioRender.com. B,C) Spearman correlation between pre-existing (pre-vaccination) anti-PEG IgG titers (n=18 from Cohort 1) and PEG-MS or Doxil nanoparticle association with monocytes, granulocytes, and B cells in human blood. D) Left: Comparing B cell association with PEG-MS nanoparticles before (Pre-Vax) and day 14 post-boost of the Comirnaty vaccination of 18 subjects across Cohort 1. p-values were derived by Wilcoxon’s matched-pairs signed-rank test. Middle & Right: spearman correlation between the change in B cell association of PEG-MS nanoparticle and the fold change (log10) in plasma anti-PEG IgG or anti-PEG IgM titers at 2 weeks post-boost compared to baseline (n=18 from Cohort 1). E) Left: Comparing monocyte association with Doxil before (Pre-Vax) and day 14 post-boost of the Comirnaty vaccination of 18 subjects across Cohort 1. p-values were derived by Wilcoxon’s matched-pairs signed-rank test. Middle & Right: spearman correlation between the change in monocyte association of Doxil and the fold change (log10) in plasma anti-PEG IgG or anti-PEG IgM titers at 2 weeks post-boost compared to baseline (n=18 from Cohort 1).

Anti-PEG IgG antibodies were boosted by a mean of 1.78-fold after vaccination, while anti-PEG IgM increased by an average of 2.64-fold after vaccination. Nine (16%) and 23 (42%) of subjects had a post-vaccination boost of anti-PEG IgG and IgM with a two-fold change, respectively.

In contrast to the vaccinated group, the 55 unvaccinated controls showed no increase and even had a slight decrease in anti-PEG IgG and IgM titers with a mean fold change of 0.92 and 0.98, respectively, over a six-month period.

The team performed a time-course analysis and showed a stepwise increase in immune response after the first and second doses of vaccination in participants with increased PEG antibody responses. PEG antibodies did not have an effect on the neutralizing antibody response to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination; also, pre-existing anti-PEG IgM antibodies correlated with a rise in reactogenicity. The increase in PEG antibodies after vaccination was linked to a rise in the association of ex vivo blood immune cells to PEG-based nanoparticles.

The anti-PEG IgG response after Pfizer vaccination was age- and gender-dependent, with females having higher titers of pre-existing anti-PEG IgG as compared to males. This was in line with previous findings and was attributed to greater exposure of females to cosmetic products containing PEG.

The age of the participants was found to be negatively correlated with pre-existing PEG levels and a rise in anti-PEG IgG following vaccination. Younger subjects were reported to have higher PEG-specific antibodies and a higher increase in anti-PEG IgG following vaccination as compared to older subjects. However, neither gender nor age influenced the change in anti-PEG IgM after vaccination.

Conclusions

Based on the study results, the authors concluded that PEG-specific antibodies are modestly boosted following the administration of lipid nanoparticle mRNA vaccines and that anti-PEG antibodies are associated with increased reactogenicity.

Even a small boost of anti-PEG antibodies following mRNA vaccination was found to affect the association of PEGylated nanomedicines with granulocytes, monocytes, and B-cells ex vivo. This underlines the importance of assessing the impact of lipid nanoparticle mRNA vaccination on the biology of other PEGylated drugs.

According to the authors, there is a need to monitor the longer-term clinical impact of the rise in PEG-specific antibodies elicited by lipid nanoparticle mRNA vaccines. Larger studies are also needed to confirm the present study data and assess whether changes in reactogenicity are linked to the modest induction or increase in anti-PEG antibodies following future vaccination regimens with further doses.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Ju, Y., Lee, W. S., Kelly, H. G., et al. (2022). Anti-PEG antibodies boosted in humans by SARS-CoV-2 lipid nanoparticle mRNA vaccine. medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2022.01.08.22268953. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.01.08.22268953v1.

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Ju, Yi, Wen Shi Lee, Emily H. Pilkington, Hannah G. Kelly, Shiyao Li, Kevin J. Selva, Kathleen M. Wragg, et al. 2022. “Anti-PEG Antibodies Boosted in Humans by SARS-CoV-2 Lipid Nanoparticle MRNA\nVaccine.” ACS Nano, June, acsnano.2c04543. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.2c04543. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsnano.2c04543.