Neurological issues, ranging from memory lapses to trouble with attention, have been widely reported after recovery from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) infection. Unfortunately, there is limited information about pathways to recovery after severe COVID hospitalization. Now, a prospective study of 4,491 patients hospitalized with COVID suggests neurological recovery can take at least a year. The study is currently available on the medRxiv* preprint while awaiting peer review.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Led by Steven L. Galetta of the New York University Grossman School of Medicine, his team found about 87% of patients discharged from the hospital after a COVID-19 illness experience cognitive impairments. Of the 87%, around half had no history of prior dementia or cognitive problems.

After 6 to 12 months, about 56% of patients experienced improved cognition. Further, anxiety symptoms improved in 45% of patients. Given the high number of people affected by neurological events after COVID-19 illness and the slow timeline for recovery, the researchers conclude that the evidence points to an urgent need for long COVID treatments.

Study details

The researchers performed a study tracking the neurological recovery of 590 patients who recovered from COVID-19 infection between March 10, 2020, and May 20, 2020.

All patients were hospitalized at four New York City hospitals. They did not consider recurrence of any previous neurological symptoms new COVID-induced neurological events.

The team conducted phone interviews with patients at 6 to 12 months regarding their neurological condition and compared their outcomes to patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 during the same time period but who had not developed neurological or cognitive deficits.

The neurological conditions under investigation included toxic-metabolic encephalopathy, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, seizure, neuropathy myopathy, movement disorder, encephalitis/meningitis, myelopathy, and myelitis.

Of the 590 patients, 242 completed the 12-month follow-up interview. The average age was 65, and 64% of patients were male.

One-third of neurological complications came after severe COVID-19 illness

Of the 242 patients, 47% reported neurological complications during hospitalization and 53% reported neurological complications after hospital discharge. The median time from neurological symptom onset following SARS-CoV-2 infection (or COVID-19 symptom onset for controls) to follow-up interview was 393 days.

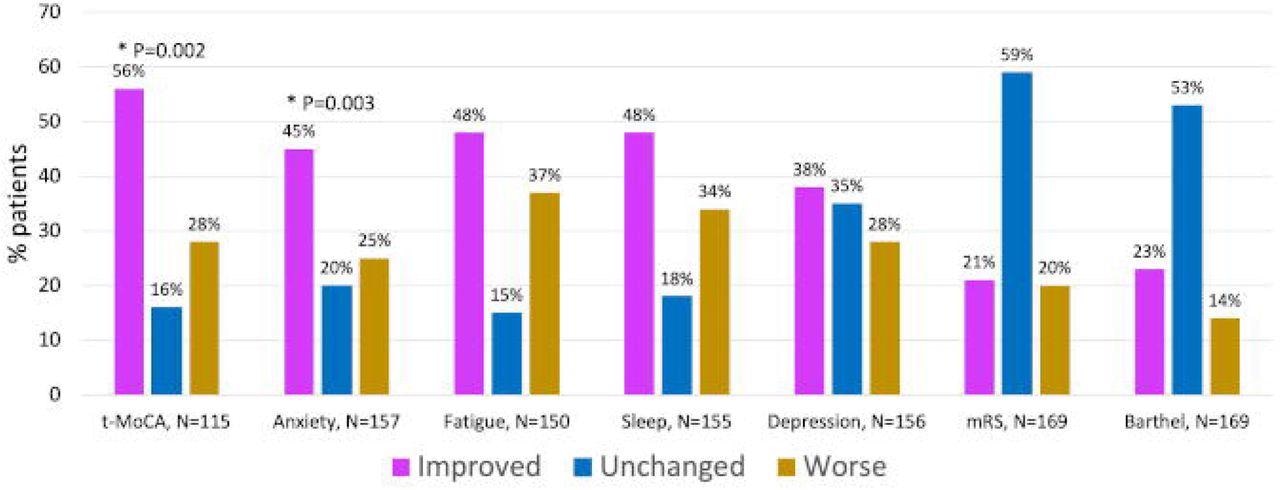

Percent of patients with improved, worse or same outcome scores between 6- and 12-months post COVID Hospitalization (N=174)

Patients who reported neurological complications during their hospital stay were more likely to have a history of seizure or dementia. In general, most neurological events occurred in patients without a history of neurological conditions.

“For example, none of the patients diagnosed with ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke had a prior history of stroke, and only 1 of 10 patients with a newly diagnosed movement disorder, had a prior movement disorder history. However, 6 of 12 patients who developed seizure in the context of acute COVID had a prior seizure disorder,” explained the team.

One-third of patients who developed neurological complications were intubated in the hospital for COVID-19 infection.

Severity of neurological complications

Twenty-four of patients reported their neurological symptoms were mild and did not interfere with their day-to-day activities compared to 39% of patients without neurological complications.

About 87% of patients who completed the 12-month follow-up interview showed at least one impairment during cognitive testing. Specifically, patients showed abnormal results for anxiety (7%), depression (4%), fatigue (9%), and sleep (10%).

Patients with neurological complications were more likely to experience severe fatigue than the control group. Of the 15 patients reporting both neurological deficits and extreme fatigue, about 47% also had toxic-metabolic encephalopathy, 27% had seizures, 13% had movement disorders, and 7% had neuropathy or Guillain-Barre Syndrome.

Recovery outcomes 6 to 12 months after hospital discharge

After 6 months, 88% of patients with neurological complications had at least one abnormal score on neurological/cognitive tests compared to 84% of patients after 12 months.

Results showed a statistically significant improvement in neurological and anxiety scores after 6 and 12 months. About 56% of patients showed improved neurological symptoms, and 45% showed improvements in anxiety symptoms.

While the findings were not significant, the researchers observed improvement in other areas as well. Specifically, 48% of patients with neurological events after COVID-19 recovery showed improvements in fatigue symptoms. Another 48% showed improvements in sleep and 38% showed improvements for depression.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Frontera JA, et al. (2022). Trajectories of Neurological Recovery 12 Months after Hospitalization for COVID-19: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. medRxiv. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.08.22270674, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.02.08.22270674v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Frontera, Jennifer A., Dixon Yang, Chaitanya Medicherla, Samuel Baskharoun, Kristie Bauman, Lena Bell, Dhristie Bhagat, et al. 2022. “Trajectories of Neurologic Recovery 12 Months after Hospitalization for COVID-19.” Neurology 99 (1): e33–45. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000200356. https://n.neurology.org/content/99/1/e33.