This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

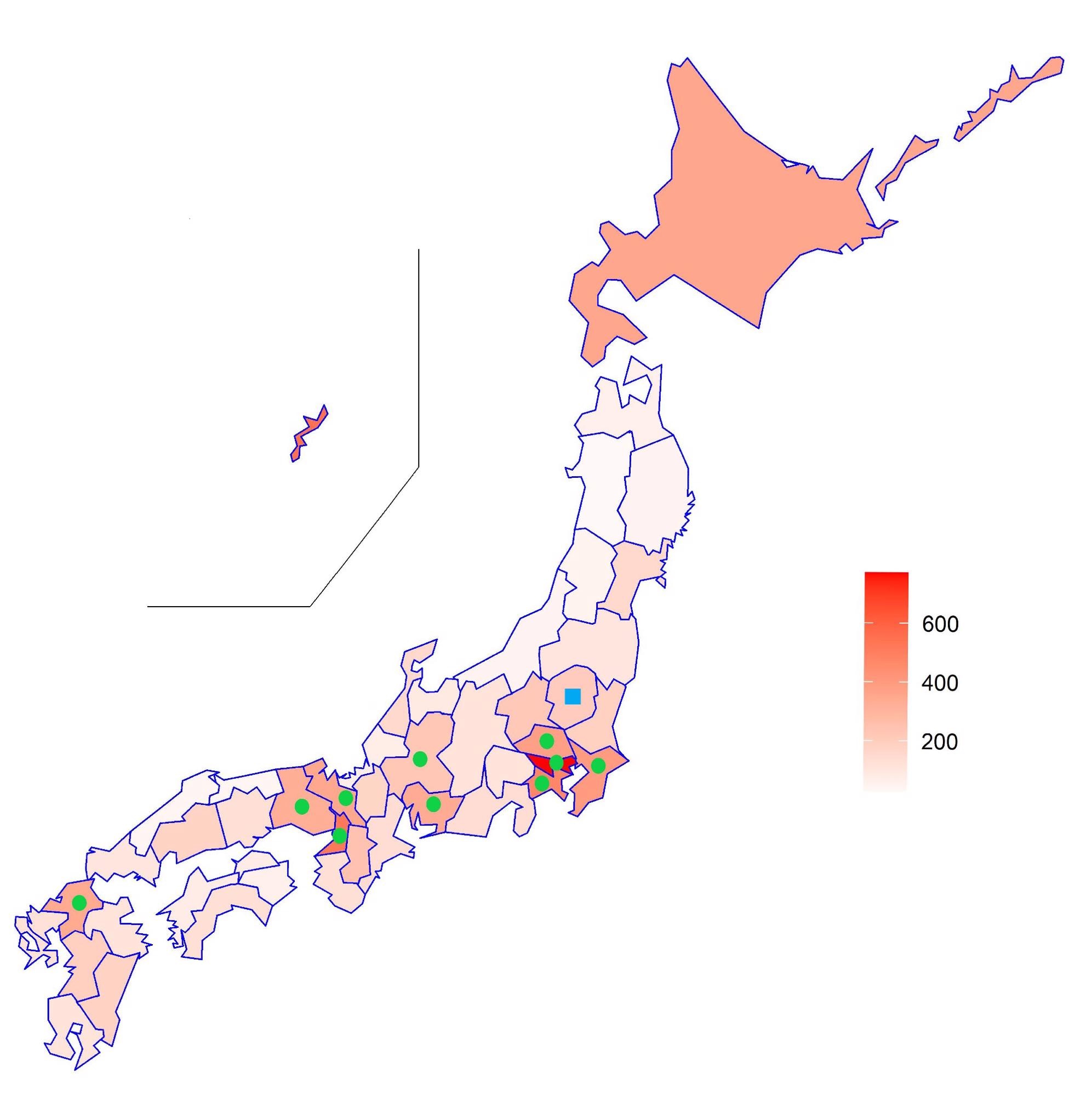

In January 2021, 11 prefectural governments in Japan declared a state of emergency (SE) and mandated restaurants and bars to close by 8 p.m. during February 2021 in hopes of suppressing COVID-19. On February 7, 2021, the SE was lifted off in the Tochigi Prefecture, while in other prefectures, it continued till the end of February.

Studies conducted during the first pandemic wave have evidenced that full-service restaurants and bars contributed to the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). However, it is unclear whether this early evidence applies to the present situation. Further, it is difficult to separate the effects of closing restaurants and bars and other SARS-CoV-2 intervention policies.

Nevertheless, during winter 2020- 2021, Japan was an ideal laboratory to explore the effects of the early closure of Japanese pubs and bars and determine the incidence of symptoms indicative of COVID-19.

Infection Rate across Prefectures. Note; The infection rate is per 100,000 persons. Circles represent the 10 prefectures that declared SE in January and continued till the end of February. The square represents Tochigi prefecture, which declared the SE in January but lifted it on February 7th.

About the study

In the present longitudinal study, researchers conducted a web-based questionnaire survey, named the Japan COVID-19 and Society Internet Survey (JACSIS) following the declaration of Helsinki to study the effects of closing restaurants and bars in 11 prefectures of Japan.

A total of 224,389 individuals in the age group of 15-79 years participated in this survey. The two-phased survey, corresponded to the first and second pandemic waves, was conducted in August-September 2020 and February 2021, respectively, and was administered by Rakuten Insight, Inc.

From the dataset in the first wave, the researchers selected 25,691 individuals, of which 4,775 individuals were excluded in the second phase. Finally, the study data covered 20,916 individuals.

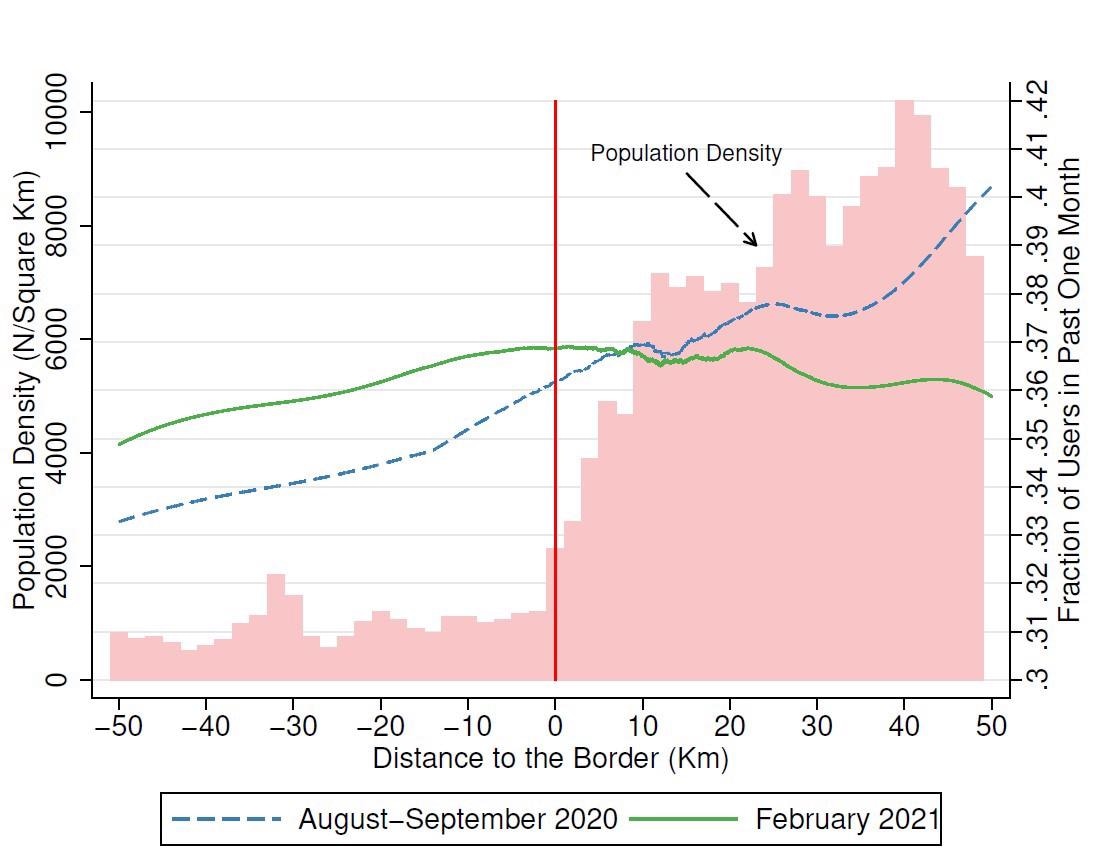

Population Density and Utilization of Japanese Pubs around the Border Note; The fraction of persons who went the Japanese pubs and bars are represented in lines which are derived from local polynomial fit. The vertical line represents the border that splits prefectures with (positive sign) and without (negative sign) the state of emergency declaration.

After taking informed consent from each participant, their samples were coded and analyzed using an anonymized database. The response rate and the follow-up rate of the study analysis were 12.5% and 81%, respectively.

For the health outcomes, the researchers considered five symptoms indicative of SARS-CoV-2, including high fever, sore throat, cough, headache, and smell and taste disorder. They used the random effect logistic regression model to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95 percent confidence intervals (CIs).

Additionally, the researchers considered each participant's age, working status, marital status, smoking, and household income level during the analysis. A binary variable with a value of one denoted a household with an annual income of 70,000 US dollars or more.

Study findings

The survey mainly covered people living closer to borders that separated prefectures with and without SE declarations. The authors observed a marked reduction in the utilization of Japanese Izakaya pubs, which are a common type of full-service restaurants in Japan, among these people. Moreover, the impact was higher among young individuals than the regular users, as indicated by the ORs of 0.688 vs. 0.754, respectively.

Notably, despite the reduction in the utilization rate, symptoms indicative of SARS-CoV-2 infection did not discernibly decrease, except cough among college graduates. Further, as expected, among the elderly, no changes were observed in both the utilization and the symptoms.

The additional effects of early closure, though not null, are limited. There are two likely explanations for this: i) the effectiveness of the early closure varied with daily preventive behaviors. In the second pandemic wave, most Japanese knew the importance of wearing masks and washing hands frequently. Also, in Japan, these behaviors were high compared to other countries, including the US, because of its collectivist culture; ii) early closure affected only the high-risk subset of the population, prone to other risky behaviors. Even if restaurants and bars weren't closed, it is possible that they eventually became infected as they tended to go out and not avoid crowds.

Conclusions

Overall, the authors recommended successfully implementing moderate SARS-CoV-2 interventions rather than taking away the freedom to do business from full-service restaurants and bars. Even from the perspective of public policy inferences, the early closure of full-service restaurants and bars, in the absence of other complementing policies, is not an efficient way to suppress SARS-CoV-2. Given these non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) are implemented, a combination of moderate NPIs, such as bans on small gatherings, early detection, and self-isolation, would perform better than only targeting full-service restaurants and bars. Furthermore, with a sufficiently high vaccination rate in present Japan, weaker intervention measures, such as restricting the number of seats served per table, could also effectively replace the earlier closure policy.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Reo Takaku, Izumi Yokoyama, Takahiro Tabuchi et al. SARS-CoV-2 Suppression and Early Closure of Bars and Restaurants: A Longitudinal Natural Experiment, February 21 2022, PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1270382/v1, https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-1270382/v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Takaku, Reo, Izumi Yokoyama, Takahiro Tabuchi, Masaki Oguni, and Takeo Fujiwara. 2022. “SARS-CoV-2 Suppression and Early Closure of Bars and Restaurants: A Longitudinal Natural Experiment.” Scientific Reports 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16428-4. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-16428-4.