Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants have displayed novel characteristics, including increased transmission and more robust evasion of the human immune system. This necessitates the development of new coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines that could target the regions that are more conserved in SARS-CoV-2.

Study: Adenovirus-Vectored SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Expressing S1-N Fusion Protein. Image Credit: F8 studio / Shutterstock

Study: Adenovirus-Vectored SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Expressing S1-N Fusion Protein. Image Credit: F8 studio / Shutterstock

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

About the study

In the present study, researchers described the generation of an adenovirus-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, along with the efficiency of a heterologous vaccine booster dose administered with a subunit recombinant SARS-CoV-2 vaccine.

The team subcloned the SARS-CoV-2 spike 1 (S1) protein and wild-type nucleoprotein (N) gene to produce pAd/SARS-CoV-2-S1N. The Ad5.SARS-CoV-2-S1N (Ad5.S1N) was subsequently made using homologous recombination in order to create E1/E3 deleted replication-deficient human type 5 adenovirus that expressed the SARS-CoV-2-S1 protein. The viral expression due to the adenoviral candidate was detected by infecting the A549 supernatant with Ad5.S1N and assessing the supernatant using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blot analysis. The team subsequently recognized the recombinant SARS-CoV-2-S1N proteins using the polyclonal N and S1 antibodies.

The immunogenicity of Ad5.S1N was compared to that of Ad5.S1 by evaluating the endpoint titers of S1 specific immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgG1, and IgG2a in the serological samples of mice vaccinated either via intranasal (I.N.) delivery or subcutaneous (S.C.) injection and of control mice. The serum samples collected were diluted to estimate the endpoint titers using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

The team also employed a microneutralization assay (NT90) that tested the ability of the serum samples to neutralize SARS-CoV-2 infectivity. Serum samples obtained from mice six to eight weeks post-vaccination were also tested for SARS-CoV-2-specific neutralizing antibodies. S1 and N-specific cellular immunity in vaccinated mice were determined by quantifying interferon-γ.+ (IFNγ.+), cytotoxic (CD8+), and CD4+ T-cell responses by performing flow cytometry and intracellular cytokine staining (ICS).

Furthermore, the team explored the primary and booster vaccine administration strategies in the form of homologous and heterologous vaccination schedules. The efficiency of a heterologous schedule with Ad5.S1N administered S.C. as the primary vaccine boosted by recombinant subunit S1 wild-type (WT) protein was also evaluated.

Results

The study results showed that the endpoint titers of S1-specific IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a for both Ad5.S1 and Ad5.S1N were comparable. However, the S.C. administration of Ad5.S1 and Ad5.S1N showed a significant increase in the IgG titers up to two weeks after one vaccination dose as compared to the control group. On the other hand, IgG titers after I.N administration of Ad5.S1 and Ad5.S1N increased to levels similar to that of S.C. injection three weeks after the vaccination. The similar titers of IgG1 and IgG2a induced by Ad5.S1 and Ad5.S1N indicated a balanced T-helper 1 (Th1) and Th2 cell response.

Furthermore, the team found no neutralizing antibody responses in the serum of control mice. However, neutralizing antibodies were observed in mice vaccinated with Ad5.S1 and Ad5.S1N six weeks after vaccination. Notably, the neutralizing antibody response for S.C injection was of a lower degree than that for I.N. delivery for both Ad5.S1 and Ad5.S1N vaccinations.

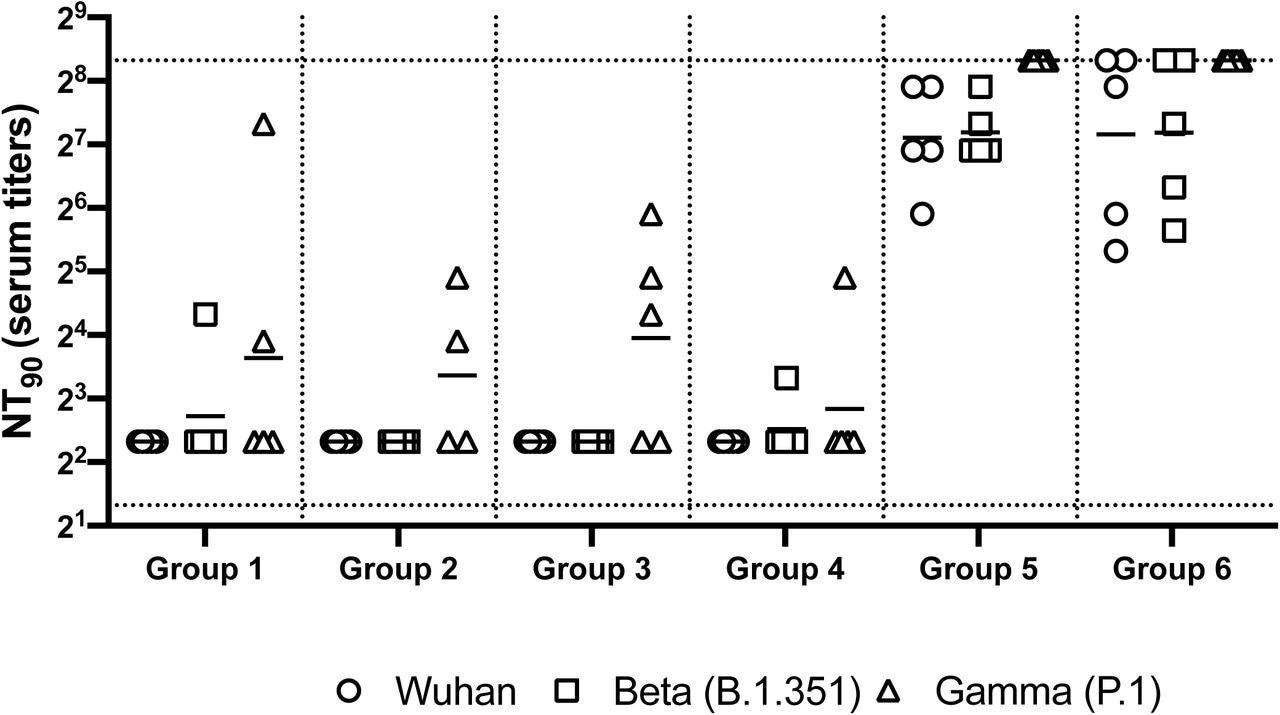

Neutralizing antibody responses in mice 7 weeks post heterologous prime-boost immunization. Group 1 prime and homologous boost 45ug rS1 WT. Group 2 prime and homologous boost 45ug rS1 B.1.351. Group 3 prime and homologous boost with 45ug rS1 WT+B.1.351. Group 4 prime 45ug rS1 WT and heterologous boost 45ug rS1 B.1.351. Group 5 prime 1×1010 v.p. Ad5.S1N and heterologous boost 45ug rS1 WT. Group 6 prime 1×1010 v.p. Ad5.S1N and heterologous boost 45ug rS1 B.1.351. Serum from immunized mice was tested for neutralizing antibodies using a plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) with three different SARS-CoV-2 strains from Wuhan, South Africa (Beta B.1.351), or Brazil (Gamma P.1). Neutralization of Wuhan strain represented by circle, neutralization of Beta B.1.351 represented by square, and neutralization of Gamma P.1 represented by triangle. Serum titers that resulted in a 90% reduction in SARS-CoV-2 viral plaques (NT90) compared to the virus control are reported seven weeks post initial vaccination, and bars represent geometric means (N = 5 mice per group). Results are from a single animal experiment. No neutralizing antibodies were detected in serum PBS control group (not shown). This experiment was conducted once.

The researchers also remarked that the I.N. delivery of Ad5.S1 or Ad5.S1N did not result in increased systemic immunity by S1- or N-specific CD8+ T cells as compared to the I.N-administered control mice. However, S.C. injection caused significant improvement in the systemic immunity by S1-specific IFNγ.+ CD8+ T cells as compared to the I.N. administration in the vaccinated and the control cohorts as well as the S.C. injections in the control mice. This indicated that a single vaccine dose of Ad5.S1 or Ad5.S1N administered by either S.C. or I.N. resulted in a significant S1-specific IgG response. Moreover, the addition of the N protein through the Ad5.S1N vaccine increased the induction of S1-specific CD8+ T-cells.

The team observed that a homologous vaccination schedule with Ad5.S1N administered I.N. as prime and S.C. as a booster dose along with Ad5.S1N administered S.C. prime and S.C. recombinant S1 booster dose showed substantially higher levels of IgG three and six weeks after vaccination as compared to the control group. In contrast, Ad5.S1N administered as S.C. prime and S.C. booster dose showed no improvement in IgG levels.

Conclusion

The study findings highlighted the potential of Ad5.SARS-CoV-2-S1N as a novel COVID-19 vaccine due to its induction of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antigen-specific cellular and humoral immune responses. In particular, the heterologous Ad5.SARS-CoV-2-S1N primary and subunit recombinant S1 protein booster vaccine schedule has shown high efficiency against COVID-19 as well as emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Adenovirus-Vectored SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Expressing S1-N Fusion Protein, Muhammad Sohaib Khan, Eun Kim, Alex McPherson, Florian J Weisel, Shaohua Huang, Thomas W Kenniston, Elena Percivalle, Irene Cassaniti, Fausto Baldanti, Marlies Meisel, Andrea Gambotto, bioRxiv, 2022.05.09.491179, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.09.491179, https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.09.491179v2

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Khan, Muhammad S, Eun Kim, Alex McPherson, Florian J Weisel, Shaohua Huang, Thomas W Kenniston, Elena Percivalle, et al. 2022. “Adenovirus-Vectored SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Expressing S1-N Fusion Protein.” Antibody Therapeutics 5 (3): 177–91. https://academic.oup.com/abt/article/5/3/177/6633990.