Studies have reported that mucosal immune responses prevent SARS-CoV-2 replication at the entry point and reduce onward viral transmission; however, data on mucosal humoral immunity and their correlation with systemic immune responses among COVID-19 convalescents are limited. In addition, research has reported on the potentiation of immune responses-post vaccination; however, whether the immune enhancement is due to passive plasma Ab transfer to mucosae or whether COVID-19 vaccinations can recall mucosal responses primed by SARS-CoV-2 infections needs further investigation.

Over time, SARS-CoV-2 has evolved with the emergence of multiple variants of concern (VOCs) having higher transmissibility and immune-evasiveness. In particular, the Omicron variant and subvariants have shown less susceptibility to vaccination-induced immune responses. Immunity generated as a combined effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination may strengthen immune combat against Omicron and other VOCs.

About the study

In the present multicentre longitudinal study, researchers evaluated the durability of mucosal immune responses to severe COVID-19 and the added advantage of subsequent COVID-19 vaccinations.

Clinical information, plasma, and nasal samples were obtained prospectively from hospitalized COVID-19 adult patients (n=446) from February 2020 to March 2021 from the PHOSP-COVID and ISARIC4C (international severe acute respiratory and emerging infection consortium 4C) consortia. Samples were obtained through nine days of hospitalization and/or at intervals during convalescence periods (one month to 14 months post-discharge).

Samples obtained at six months and 12 months post-vaccination between September 2020 and March 2022 covered the beginning of the UK COVID-19 vaccination campaign, and COVID-19 severity was categorized based on the World Health Organization (WHO) clinical progression scores. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgA titers against SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (NP), spike (S) proteins of the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 strain, and Delta and Omicron BA.1 VOCs were assessed by electrochemiluminescence analysis.

The findings were correlated with those of pseudotype neutralization assays performed on plasma samples. In addition, the PubMed database was searched using search terms such as “nasal,” “mucosal,” “IgA,” “antibody,” “SARS-CoV-2”, “COVID-19”, “vaccination,” and “convalescent” for relevant studies that were published prior to July 20, 2022, in English.

As a result, three studies on the longevity of nasal Ab responses were analyzed that showed nasal Ab persistence for three to nine months. However, the studies included patients with mild SARS-CoV-2 infections and small sample sizes. In addition, a study conducted on home-care persons (n=107) showed elevated salivary IgG titers after two mRNA (messenger ribonucleic acid) vaccinations, whereas another one showed increased nasal IgG and IgA titers after seven to 10 days of vaccination among SARS-CoV-2-exposed persons.

Results

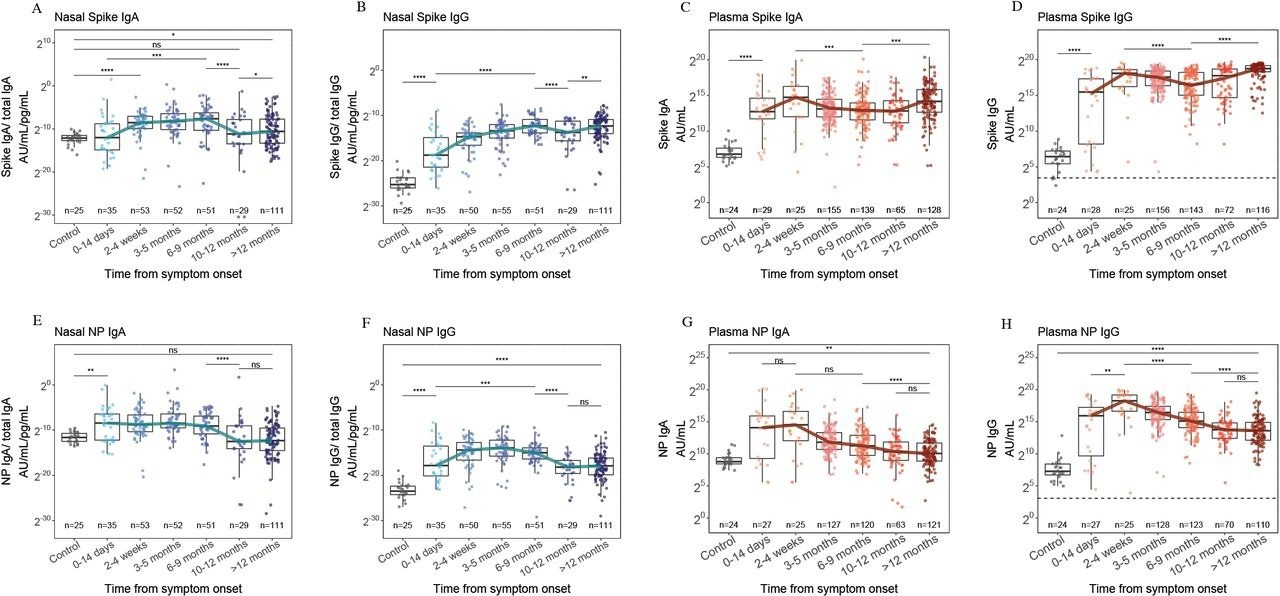

In total, 569 and 356 plasma and nasal samples were obtained, of which 338 and 143 were obtained from the same person at different time intervals, respectively, and paired nasal and plasma samples obtained at the same time point were available for 174 persons. Robust nasal anti-NP and anti-S IgA titers were found within four weeks of symptom onset, which waned after nine months.

Nasal IgA (A), nasal IgG (B), plasma IgA (C) and plasma IgG (D) responses to S from ancestral SARS-CoV-2, 12 months after symptom onset and compared to pre-pandemic control samples (grey). Nasal IgA (E), nasal IgG (F), plasma IgA (G) and plasma IgG (H) responses to NP of ancestral SARS-CoV-2, 12 months after symptom onset and compared to pre-pandemic control samples. The blue and red lines indicate the trajectory of median titers across each time point. The horizontal dashed line indicates the WHO threshold for a seropositive titer. * = p<0·05, ** = p<0·01, *** = p<0·001, **** = p<0·0001.

On the contrary, nasal and plasma anti-S IgG titers, which appeared within two weeks of symptom onset, were persistently high for ≥1 year, with 2181-fold higher plasma neutralizing titers against all VOCs tested after nine months of vaccination. Nasal IgG and IgA anti-S titers increased after ten months; however, only a 1.5-fold median change was only observed for IgA, and anti-NP IgG and IgA responses persisted at low levels after nine months.

Two individuals developed re-infections (elevated anti-S and anti-NP IgG titers). Further, among 33 persons with known vaccination status and from whom pre- and post-vaccination samples were obtained, anti-S titers increased, whereas anti-NP titers decreased. Most participants had been vaccinated between the six months to one-year post-vaccination period, coinciding with increases in plasma and nasal IgG and IgA anti-S titers against all VOCs, although nasal IgA titers changed slightly.

Among samples obtained a year post hospitalization, no association was found between plasma IgG titers and nasal IgA titers, indicating that nasal IgA humoral responses differed from plasma responses and were boosted minimally by vaccinations. Nasal IgA titer diminution post-nine months of natural SARS-CoV-2 infection and the slight impact of COVID-19 vaccination could be due to the lack of long-term nasal mucosal defenses against SARS-CoV-2 re-infections and the minimal impact of vaccination on viral transmission. Infection-induced nasal Ab titers for VOCs circulating before Omicron showed binding with Omicron in vitro better than that with plasma Ab.

Overall, the study findings showed durable plasma and nasal IgG immune responses to the SARS-CoV-2 B.1 strain, Delta VOC, and Omicron VOC that were enhanced by vaccination. However, nasal IgA titers did not correlate with plasma IgA titers, showed waning within nine months, and were not boosted significantly by COVID-19 vaccinations. The findings indicated that vaccination after natural SARS-CoV-2 infection was unable to sufficiently recall mucosal immune responses and highlighted the need to develop vaccines that induce durable and robust mucosal anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunity.

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

This news article was a review of a preliminary scientific report that had not undergone peer-review at the time of publication. Since its initial publication, the scientific report has now been peer reviewed and accepted for publication in a Scientific Journal. Links to the preliminary and peer-reviewed reports are available in the Sources section at the bottom of this article. View Sources

Journal references:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Nasal IgA wanes 9 months after hospitalisation with COVID-19 and is not induced by subsequent vaccination. Felicity Liew et al. medRxiv preprint 2022, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.09.22279759, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.09.09.22279759v1

- Peer reviewed and published scientific report.

Liew, Felicity, Shubha Talwar, Andy Cross, Brian J. Willett, Sam Scott, Nicola Logan, Matthew K. Siggins, et al. 2022. “SARS-CoV-2-Specific Nasal IgA Wanes 9 Months after Hospitalisation with COVID-19 and Is Not Induced by Subsequent Vaccination.” EBioMedicine 0 (0). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104402. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/ebiom/article/PIIS2352-3964(22)00584-9/fulltext.