The obesity epidemic challenges public health in the developed world, reducing the quality of life and threatening health even as it demands heavy investments in preventive and therapeutic medical care. The discovery of drugs that can modulate gut-brain pathways could be a potential breakthrough in this area, helping obese individuals to lose weight and diabetes sufferers to regain metabolic normalcy, at least as well as bariatric surgery.

Study: Dual gut hormone receptor agonists for diabetes and obesity. Image Credit: SHISANUPONG1986 / Shutterstock

Study: Dual gut hormone receptor agonists for diabetes and obesity. Image Credit: SHISANUPONG1986 / Shutterstock

Introduction

In addition to reducing T2DM risk and severity, reducing body mass by 5-10% has long been known to decrease obesity risk. It is evident that obesity is the primary cause of T2DM.

The most common methods to achieve this desirable outcome include diet and lifestyle alterations. However, they are not efficient enough to maintain an optimal body weight for most people. While a number of medications have emerged for the treatment of T2DM, some of them, including insulin, promote weight gain, antagonizing their favorable effect on health.

A number of weight loss pills and other obesity-fighting medications have been resorted to, but they have many potentially serious side effects. Bariatric surgery is more effective, with the loss of a good deal of weight maintained over the years and the restoration of insulin sensitivity. However, it is expensive and risky, making it non-ideal for many people.

The recent focus of research has been on using gut hormones to reduce the metabolic abnormalities underlying T2DM and obesity. Gut hormones are involved in the bidirectional communication between the brain and the gut.

GLP1R agonism

One such pathway is mediated by the gut peptide glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1), analogs of which have been studied in some depth for their effects in these areas. GLP1 is produced in the small intestine and increases insulin release after meals, thus lowering blood glucose levels. However, this peptide is quickly inactivated and destroyed by a protease enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase IV, which meant it was of little clinical use.

Soon enough, a synthetic protease-resistant GLP1R agonist, exenatide, was developed based on the lucky discovery of a protease-resistant form of GLP1R peptide called exendin-4, in Gila monster venom. Exenatide was produced and gained approval for the treatment of T2DM in 2005. This was followed by liraglutide, with a longer half-life, approved for treating obesity at a higher dosage in 2010.

Semaglutide is a GLP1 receptor (GLP1R) agonist that has been approved for use in obesity, bringing about both a 15% weight loss in clinical trials and attenuating hyperglycemia in T2DM patients. It was approved for use in T2DM in 2017 and in obesity in 2021.

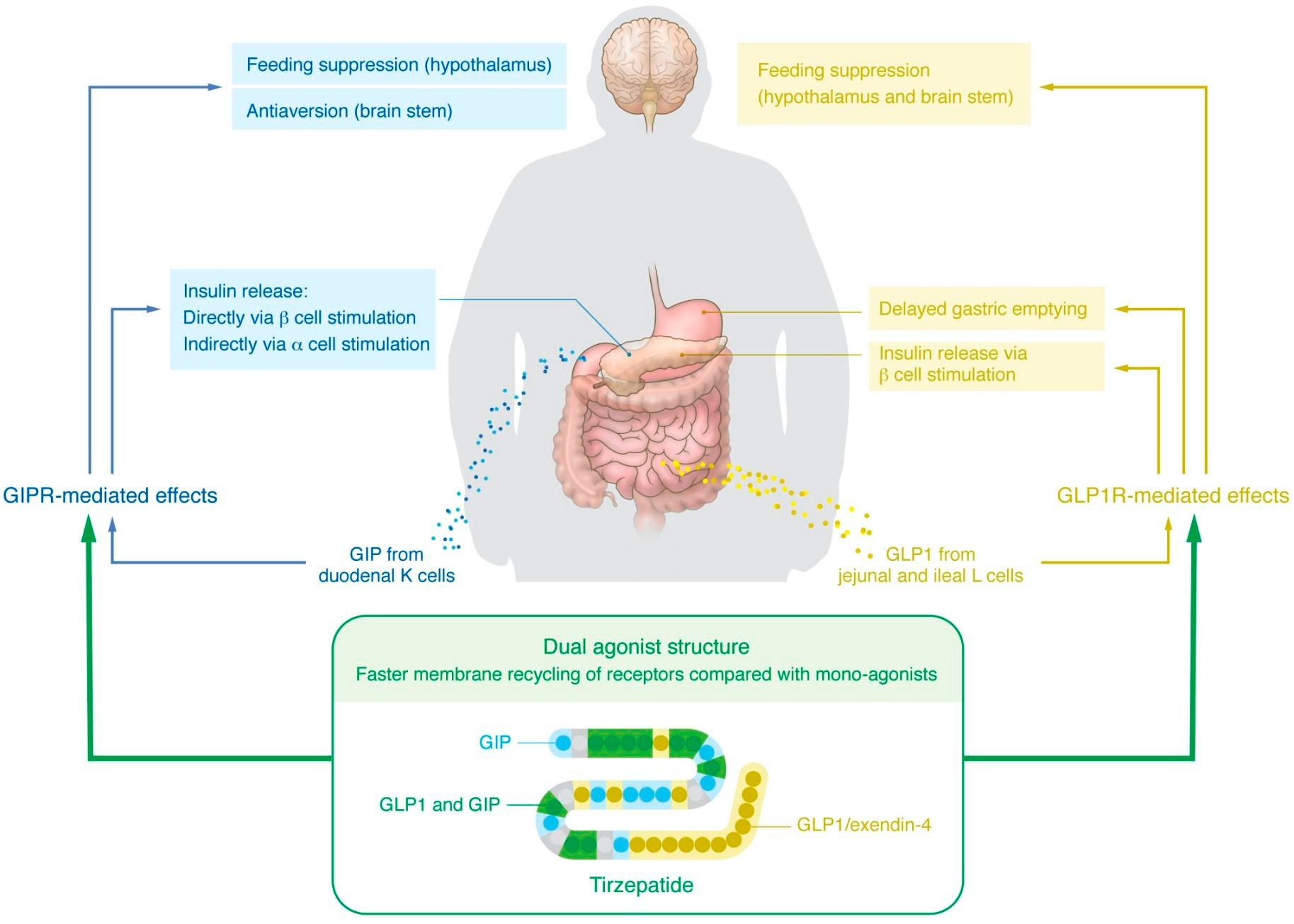

Established and proposed mechanisms underlying the glucoregulatory and weight loss effects of GIP/GLP1R co-agonism.

Established and proposed mechanisms underlying the glucoregulatory and weight loss effects of GIP/GLP1R co-agonism.

Tirzepatide – a combination therapy

This was followed recently by tirzepatide, a dual agonist of both the gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor/ GLP1R (GIPR/GLP1R). The gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP) increases insulin production and release, and GIPR agonists were found in mouse experiments to produce a reduction in body weight. Later, in 2013, an engineered dual agonist at GIPR/GLP1R was synthesized and demonstrated to reduce blood glucose levels and body weight in experimental animals.

With the safety and efficacy of such co-agonists being established, tirzepatide was the first such drug to be approved for T2DM treatment in 2022. In obese patients, it triggers the loss of over a fifth of the body weight.

But how does it achieve this remarkable effect? Molecular-level research shows that GIP acts on pancreatic beta-cell GIPR to boost the post-prandial increases in insulin levels. Meanwhile, GIPR on pancreatic alpha-cells also causes increased insulin release by triggering glucagon secretion. And finally, GLP1R itself increases insulin release.

The independent activity at both receptors may be responsible for the extraordinary effectiveness of tirzepatide. It is still a matter of debate, but GIPR in the brain may be responsible for the weight loss associated with this drug, specifically in the hypothalamic centers linked to feeding. Notably, at a dose that does not bring about weight loss, a GIPR agonist can boost GLP1 analog-linked reductions in body weight.

Several mechanisms are being investigated, such as the faster recycling of GLP1R within the cell with this co-agonist compared to a pure GLP1R agonist or a broader spectrum of aversion to eating created by GIPR agonists. If the latter is true, this will account for increased activity at GLP1R without the adverse gut effects like nausea typically associated with GLP1R agonists.

In any case, tirzepatide provides a combination therapy for both T2DM and obesity, hopefully, the first of many.

Future prospects

Further polyagonists are being developed that may revolutionize the medical treatment of these lifestyle conditions while avoiding the disadvantages associated with bariatric surgery. These include those that act as agonists at glucagon receptors/GLP1R, reducing the hyperglycemia induced by glucose while retaining its favorable metabolic effects. One such is cotadutide, which reduces body weight and blood glucose levels via the GLP1R but prevents non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)via glucagon receptor activation.

Such compounds have shown favorable effects in animals and human trials, with evidence of long-term weight loss at over a year with one drug. Though the patients lost only an average of 5% body weight at this point, other glucagon effects, such as lipolysis and loss of appetite, as well as fat-burning to produce body heat, could help to improve fatty liver changes. This is a burning question today, with increasing numbers of NAFLD-related cirrhosis patients requiring liver transplantation.

Triagonists are also being developed that act at all these three receptors to produce a greater magnitude of effect on metabolic abnormalities. These are being tested in clinical trials at present.

What are the implications?

Currently, GLP1R agonists, including tirzepatide have to be given via injections, beginning with small doses to minimize the disagreeable, or in some cases, intolerable, side effects. Oral formulations are being produced for some drugs but are inferior in their efficacy.

The pressing need is for potent oral formulations of small-molecule drugs that can act as polyagonists and allosterically-acting drugs at the GIP, GLP1R, and glucagon receptors, among others. These must bring about significant and durable weight loss and should not cause rebound weight gain when they are stopped. Their potential risks, including gallstones, pancreatitis, and thyroid cancer, are serious and must be carefully studied.

“The rapid expansion of molecular tools to unravel the basic mechanisms underlying gut-brain axis control of feeding and metabolism, coupled with efforts to harness these pathways with the next generation of engineered polyagonists, will further advance the development of precision medicine for obesity, T2DM, and related diseases.”

Journal reference:

- Bass, J. et al. (2023). Dual gut hormone receptor agonists for diabetes and obesity. Journal of Clinical Investigation. Dual gut hormone receptor agonists for diabetes and obesity. https://www.jci.org/articles/view/167952