Additionally, they investigated the role of sweeteners in gastrointestinal (GI) cancer pathways, such as cellular cycle arrest and apoptosis.

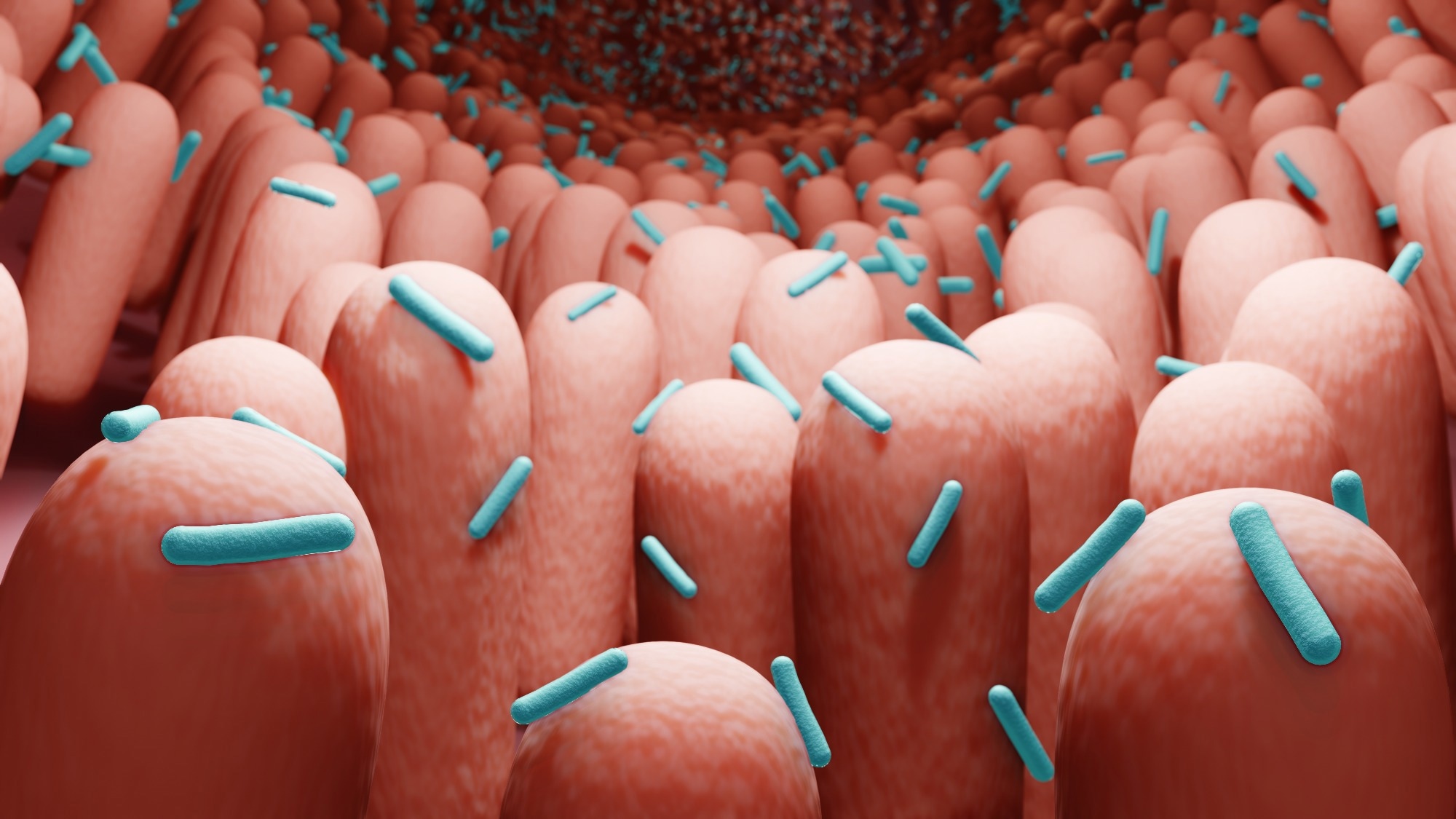

Study: Sweeteners and the Gut Microbiome: Effects on Gastrointestinal Cancers. Image Credit: ART-ur/Shutterstock.com

Study: Sweeteners and the Gut Microbiome: Effects on Gastrointestinal Cancers. Image Credit: ART-ur/Shutterstock.com

Background

Studies have shown the modulatory effects of diet on gut flora, bacteria, fungi, and viruses, which regulate the host's metabolism, growth, and immunity.

Non-nutritive sweeteners (NNS) use is increasing in the food industry globally, raising great interest among researchers to evaluate the effect of NNS on a host's gut microbiome and physiological status.

Some studies suggest NNS acts directly on the gut barrier, while others suggested interactions between NNS and taste receptors having a high affinity to gut microbes. However, data to support these possible mechanistic interactions is limited.

Studies have also implicated sweeteners with cancer etiology, particularly GI cancer, despite conflicting findings from various studies. There is a knowledge gap about the potential effects of sweeteners on the gut microbiome and overall health.

About the study

The researchers extensively searched Medline, Scopus, and PubMed databases and identified 104 articles describing sweetener metabolism by gut bacteria and their role in GI cancers.

Specifically, they examined three natural, steviol glycoside, glycyrrhizin, and neohesperidine dihydrochalcone, and two synthetic sweeteners, saccharin and sucralose, and the role of the gut microbiome in their metabolism.

Steviol glycosides is a natural sweetener with high sweetness intensity, specifically metabolized by gut-inhabiting Bacteroides species. Notably, steviol glycosides are not absorbed in the upper GI tract.

Glycyrrhizin, a triterpene saponin glycoside, is almost 200 times sweeter than sucrose. It is one of the 300 bioactive compounds of licorice.

In the gut, Eubacterium and Bacteroides species metabolize it into glycyrrhizic acid and 18β-glycyrrhizic acid 3-O-monoglucuronide, which are further processed in the liver and then excreted.

Neohesperidin dihydrochalcone (NHDC) is a natural sweetener found in citrus fruits. Its metabolism by the gut microbiome is not fully understood.

Among artificial sweeteners, non-caloric saccharin has a sweetness intensity 300 times higher than sucrose. The human body does not metabolize and excretes it via urine and feces.

Researchers have not yet established its effect on the gut microbiome's composition and function.

Sucralose is a low-caloric synthetic sweetener 600 times sweeter than sucrose, which humans also fail to metabolize.

In mice, its administration has been shown to influence amino acid regulation and chronic inflammation; however, only further research could demonstrate its effects on humans.

Study findings and conclusions

Most reported studies showed that sweeteners lacked carcinogenicity and genotoxicity and were safe when consumed in moderation. Moderate sweetener consumption is deemed a safe substitute for refined sugar. It could also positively impact cancer development and progression.

A study in 2014 used isosteviol, derived from steviol glycoside, to create a potential anti-tumor agent. They tested the effect of the sosteviol triazole conjugates on different cancer cell lines and found they had anti-proliferative activities.

With more studies ensuring the stability and safety of such an agent, it could be tested further in preclinical and clinical trials as a cancer therapeutic.

Studies have shown that steviol derivatives and glycyrrhizic acid have potent cytotoxic effects on different cancer cell lines. Studies have shown they inhibit apoptosis in GI cancer cells and induce apoptosis in colon cancer cells.

Additionally, these sweeteners inhibit the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) expression, which reduces inflammation and has therapeutic effects on cancer.

Studies have also shown how these sweeteners induce cell cycle arrest in gastric and colorectal cancer cells by modulating proteins participating in the G1 phase of the cell cycle.

Further, researchers highlighted the controversial link of aspartame to cancer. Limited studies have shown that aspartame can affect the gut microbiome and increase fasting glucose concentrations, but its association with gastrointestinal cancers is inconclusive.

Furthermore, this review uncovered that many studies misreported participants' sweetener consumption. They had selection bias and residual confounding; thus, these studies inadequately evaluated the causal link between specific gut bacterial species and sweetener metabolism.

Addressing these limitations in the sweetener research domain is needed to improve research outcomes.

Future research should also evaluate the safety, taste, and impact of flavonoids and phytochemicals on the gut microbiome, as these compounds have recently garnered attention as healthier substitutes for sweeteners.