CMA is globally recognized as the most prevalent and complex infant food allergy, with its estimated prevalence varying from 1.8% to 7.5% for Immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated cases between 1973 and 2008; however, a 2023 European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) report suggests a confirmed prevalence of below 1%. It often marks the start of the allergic journey in early childhood, but effective prevention strategies remain elusive. Accurate diagnosis and management by healthcare professionals (HCPs) are crucial for fostering tolerance development. Major organizations like the World Allergy Organization (WAO), European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology

(EAACI), Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA2LEN), and ESPGHAN have developed guidelines for CMA management. However, these guidelines are frequently underutilized due to a lack of awareness or implementation challenges in daily practice. Further research is essential to develop effective strategies for preventing and managing CMA, given its complex nature and the existing gaps in guideline implementation and real-world clinical application.

Prevalence and incidence of CMA

The prevalence of CMA varies considerably in different studies and regions, and clinical studies and caregiver perceptions suggest a prevalence ranging from less than 1% to as high as 10%. The EuroPrevall birth cohort study found a challenge-proven diagnosis rate of 0.54% among 12,049 European children. Significant regional variations were noted, especially in the incidence of non-IgE-mediated allergies. For instance, in the United Kingdom (UK), non-IgE-mediated CMA was more prevalent than IgE-mediated cases, whereas other European countries reported different or even no data on non-IgE-mediated CMA. Further complicating the picture, recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses report widely varying prevalence rates for both self-reported and food-challenge-verified allergies to cow's milk.

In the US, specific conditions like Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome (FPIES) and Allergic Proctocolitis (FPIAP) show notable prevalence, although not always confirmed by oral food challenges. Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) also shows a significant incidence rate, with CMA being a common allergen in these cases.

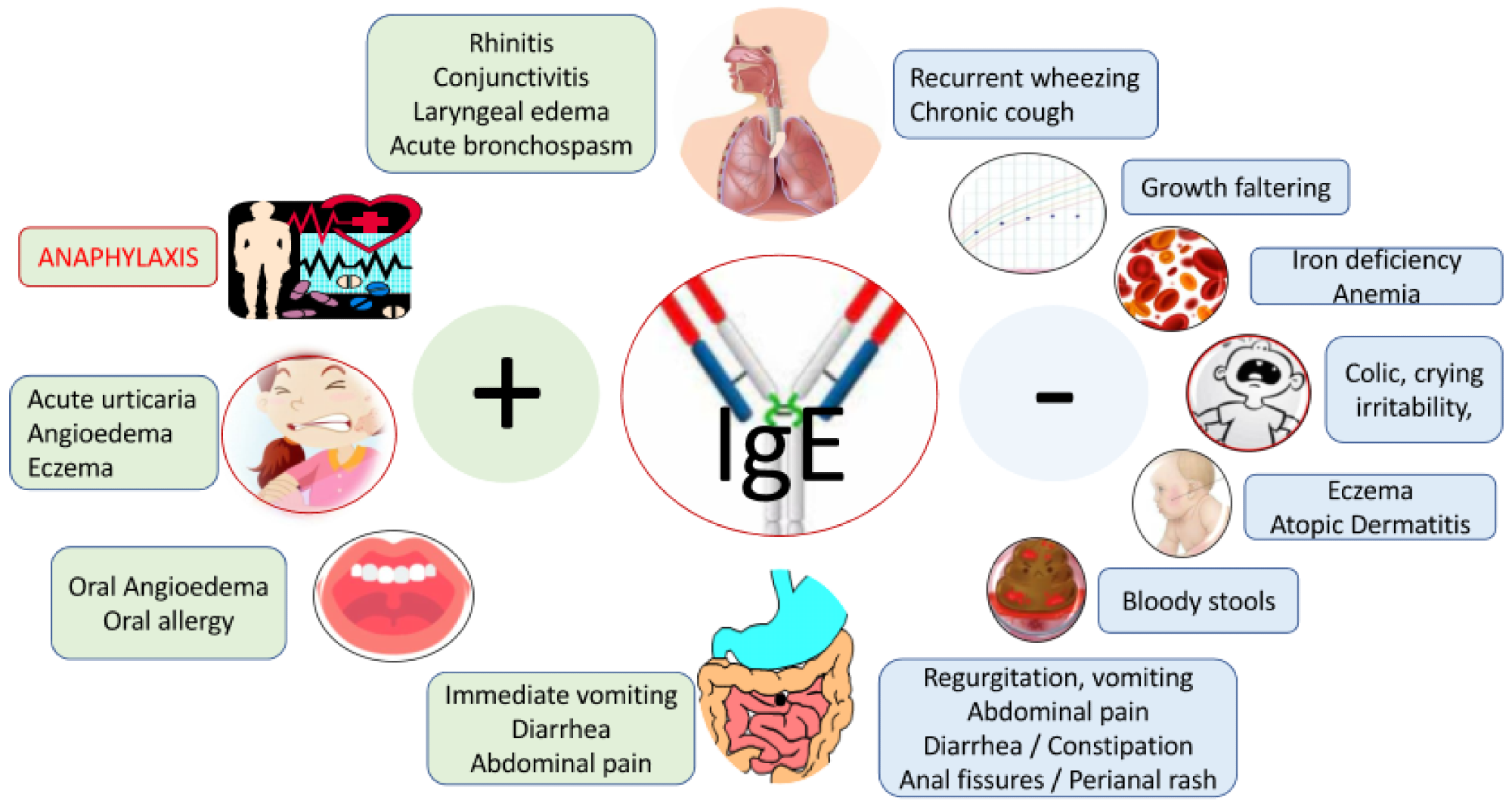

Signs and symptoms associated with cow’s milk allergy. Legend: patients may also present with mixed IgE and non-IgE CMA symptoms; none of the symptoms are specific; symptoms are unrelated to infection.

Signs and symptoms associated with cow’s milk allergy. Legend: patients may also present with mixed IgE and non-IgE CMA symptoms; none of the symptoms are specific; symptoms are unrelated to infection.

Symptoms and diagnostic challenges

CMA presents a wide array of symptoms, including anaphylaxis, which are non-specific and overlap with other diseases, and the recommended duration for diagnostic elimination diets varies based on the type of allergy viz IgE or non-IgE-mediated and EoE. While double-blind placebo-controlled food challenges (DBPCFC) are the gold standard for diagnosis, they are often impractical in daily practice. Open oral food challenges (OFC) are more commonly recommended, but their implementation and interpretation can be complex and subjective, particularly in non-IgE-mediated cases.

Challenges in conducting OFC and parental reluctance

OFCs, especially for IgE-mediated allergies, require careful medical supervision due to the risk of severe reactions. Parental reluctance to conduct OFCs or reintroduce cow's milk into their infant's diet is a significant hurdle, potentially leading to underdiagnosis or overdiagnosis of CMA.

Specific challenges in IgE and Non-IgE-mediated CMA

IgE-mediated CMA

Diagnostic tools for IgE-mediated CMA, like specific IgE measurements and skin prick tests, often result in false positives. They indicate sensitization rather than clinical allergy. The persistence of IgE-mediated CMA and the need for careful management of potential anaphylactic reactions are key concerns.

Non-IgE-Mediated CMA

Non-IgE CMA presents significant challenges in diagnosis, particularly in differentiating it from Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction (DGBI). The primary diagnostic tool is an elimination diet followed by reintroduction of cow's milk (CM), but this approach is complicated by the subjective nature of symptom reporting and the lack of specific symptoms unique to non-IgE CMA.

Implications for clinical practice

Breastfeeding should continue even when CMA or DGBI is suspected, with support from specialists as needed. Comfort formulas, though not a definitive solution, offer some benefit and are generally safe. The key question remains: should DGBI and non-IgE CMA be considered as part of a spectrum, especially given the risk of other allergic developments in children with non-IgE mediated CMA? Accurate diagnosis is crucial for effective management and anticipatory guidance.

Enhancing CMA diagnosis: The role of awareness tools

The Cow's Milk-Related Symptom Score (CoMiSS) is an instrumental tool in identifying CMA, particularly useful in clinical trials. It evaluates symptoms like dermatitis, crying, regurgitation, respiratory problems, and stool irregularities, with a score above 10 suggesting CMA. Despite its utility, there is debate over its potential role in CMA over-diagnosis. Experts advise validating such tools and using them under expert HCP guidance to prevent misdiagnosis. The reliance on subjective reporting, a critical aspect of CoMiSS, poses challenges in confirming CMA, necessitating advancements like artificial intelligence for more objective symptom assessment to enhance the tool's diagnostic precision.

Therapeutic elimination diets in CMA management

The management of CMA aims at symptom resolution, tolerance development, and normal growth. The primary strategy involves avoiding CM protein and for breastfed infants, breastmilk remains the optimal nutrition source. If breastmilk is not an option, extensively hydrolyzed formulas (eHF) are recommended for mild to moderate symptoms, though a small percentage of infants may still react due to residual peptides.

Oral immunotherapy (OIT) and Formula Options

OIT may induce tolerance in some patients, but it is not a universal solution. Though for severe cases, amino acid-based formulas (AAFs) are suggested, yet soy formulas, once controversial due to phytoestrogens, are now considered safe and nutritionally adequate.

Hydrolyzed rice formulas

Hydrolyzed rice formulas (HRFs) have gained popularity as they are completely CM-free and have shown promising results in managing CMA. Recent guidelines recognize HRFs as an alternative to eHFs, potentially becoming a first-choice option in the future. Concerns about arsenic levels in rice necessitate careful monitoring in these formulas.

Lactose Considerations and Mild CMA Management

Lactose, historically excluded from hypoallergenic formulas due to potential CM protein contamination, is now safely included due to technological advancements. In cases of mild CMA, dietary elimination might not be necessary, and symptoms can often be managed with medical interventions.

Formulas are increasingly supplemented with "biotics," viz probiotics, prebiotics, or synbiotics to mimic the gastrointestinal microbiota of breastfed infants. These additions show potential in reducing inflammation and infections, but their role in enhancing tolerance development remains unclear. Research continues on their effectiveness in managing CMA and promoting oral tolerance.

Understanding and managing the natural history of CMA

CMA usually resolves by age 3 in most children and can precede or occur alongside other atopic conditions like asthma and allergic rhinitis. The reintroduction of CM depends on the allergy type, severity, and child's age, with proactive management being key to avoid unnecessarily prolonged elimination diets.

Reintroduction strategies in infants and young children

Non-IgE-mediated CMA often resolves earlier than IgE-mediated forms, and in cases like Food Protein-Induced Allergic Proctocolitis (FPIAP), CM reintroduction can start after 6 months, with periodic reassessment until tolerance is established. For Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome (FPIES), a more extended avoidance period is recommended. IgE-mediated CMA reintroduction can be monitored through skin prick tests (SPT) and serum CM-specific IgE levels. Baked milk products are often used as initial reintroduction steps, with careful monitoring for severe reactions.

Approach for older children

Persistence of CMA beyond 3 years indicates a more severe form of the allergy. In non-IgE CMA, reintroduction is a collaborative decision with caregivers, with trials at home recommended every 6–12 months. For IgE-mediated CMA, children with severe reactions to baked milk or high CM-sIgE levels require careful monitoring and periodic reassessment. A 50% decrease in CM-sIgE over 24 months is a positive indicator of tolerance development.