Their results have wide-reaching implications for canine well-being and will interest welfare organizations, breeding groups, and dog lovers everywhere.

Study: Longevity of companion dog breeds: those at risk from early death. Image Credit: MitchyPQ / Shutterstock

Study: Longevity of companion dog breeds: those at risk from early death. Image Credit: MitchyPQ / Shutterstock

Background

There is a broad scientific consensus that humans domesticated dogs from their ancient wolf ancestors; genomic and archaeological evidence suggests this happened around 16,000 years ago.

Recent efforts at artificial selection to intensify desirable traits have led to a widespread loss in genetic diversity and a spectacular variety of phenotypic diversity. The former was ensured through breeding practices such as repeatedly using popular sires, and the aim was to maintain pedigree diversity by restricting the gene flow between breeds.

Some breed standards focused on achieving standards of physical appearance by exaggerating phenotypic characteristics, leading to various disorders related to conformation and hereditary pathology.

Studies comparing longevity between purebred and crossbred dogs have found that crossbreds have a survival advantage of 1.2-1.3 years, with researchers hypothesizing that this is partially due to ‘hybrid vigor’ caused by reductions in deleterious genes inherited from both parents in purebreds.

Whether inbreeding depression or hybrid vigor affects domestic dogs has not been conclusively established, but scientists have described approximately 700 hereditary traits and disorders; the high prevalence of diseases in many purebred populations is a cause for concern.

About the study

Researchers included 584,734 dogs in the United Kingdom with information on their breed, sex, whether they were crossbred, date of birth, postal code, death date (if the animal had died), and identifying information. Data was obtained from academic institutions, charities for animal welfare, pet insurance firms, veterinary corporations, and breed registries.

Within a breed, purebred dogs were classified as large, medium, and small in size; their cranial or cephalic index was calculated as the ratio between skull width and length, and they were then classified as long-faced or dolichocephalic, medium-proportioned or mesocephalic, and flat-faced or brachycephalic.

The research team used maximum likelihood estimation to analyze censored data and make use of all available information. The analysis included plotting Kaplan-Meier survival curves within each group and each explanatory variable, such as cephalic index, sex, size, breed, and parental lineage, and testing for statistical differences between the survival curves using pairwise log-rank tests. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to test whether proportional mortality risk differed between categories.

Findings

The 584,734 individuals included 284,734 who were deceased; approximately 27% were geriatric, 34% were senior adults, 29% were mature adults, 6% were young adults, 2% were juvenile, and 2% were puppies.

There were 4.3 purebred dogs for every crossbred dog in the sample and 1.1 males for every male; among purebreds, 21% of the dogs were brachycephalic, 63% were mesocephalic, and 16% were dolichocephalic.

Labrador retrievers, Staffordshire bull terriers, English cocker spaniels, and German shepherds were the most common breeds, and small dogs accounted for over 53% of the sample of purebreds.

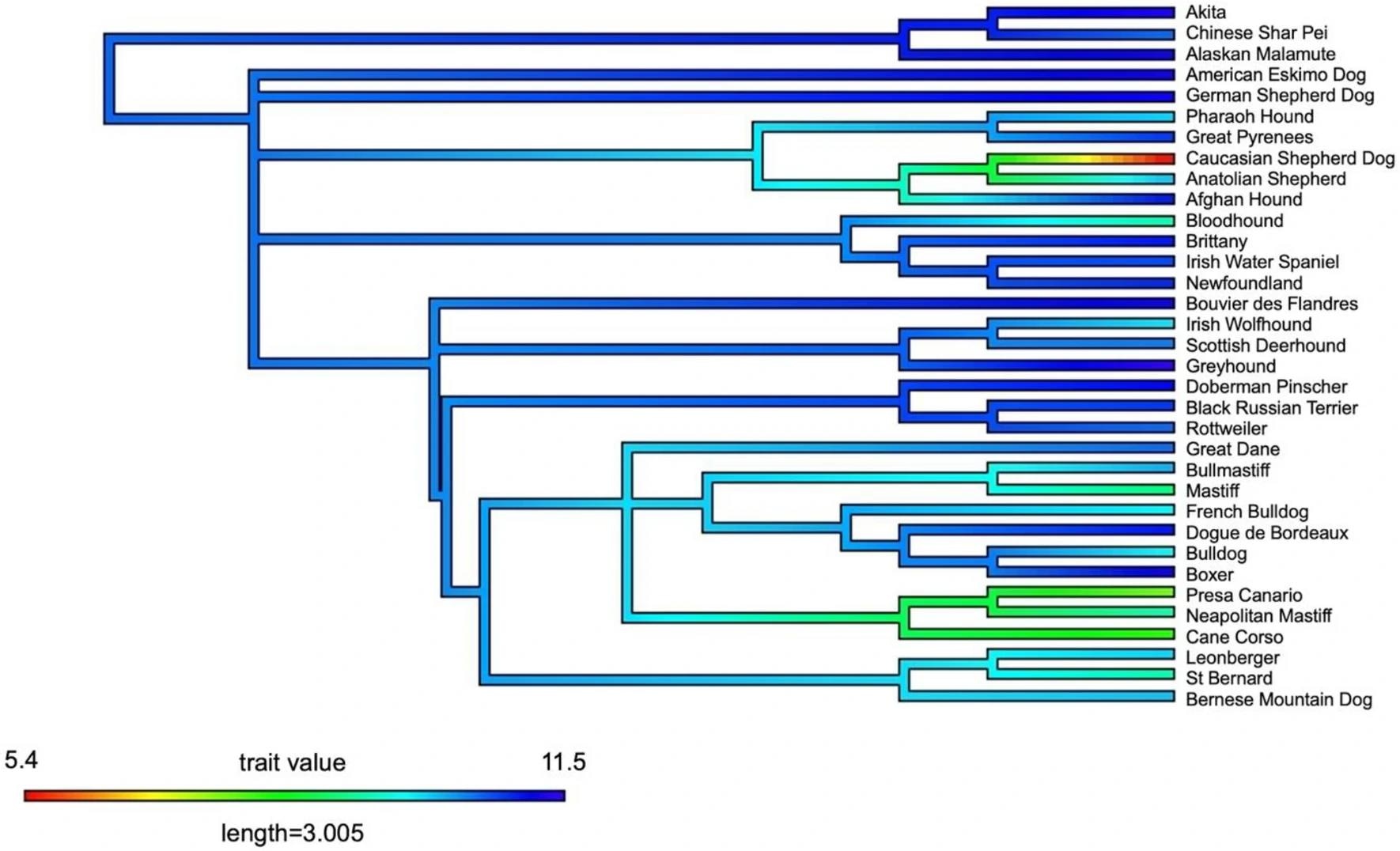

Median lifespan of the lowest quartile of breeds plotted onto the breed phylogeny. Hotter colors represent lower median lifespans.

Median lifespan of the lowest quartile of breeds plotted onto the breed phylogeny. Hotter colors represent lower median lifespans.

Survival probabilities were lowest for geriatrics and highest for juveniles, with young adults and puppies having similar chances of survival. Crossbreeds had a median survival of 12 years, while purebreds lived for a median of 12.7 years.

By slightly over 18 years of age, 95% of crossbred and purebred individuals had died; females showed a slight advantage in survival over males. When compared with crossbred survival, 47% of purebreds showed more prolonged median survival, 26% showed shorter median survival, and the remaining showed no significant difference.

There were significant variations in longevity across breeds, with mastiffs, St. Bernards, bloodhounds, and bulldogs being among those at risk of early death. Breeds with the lowest risks of dying early included border terriers, Italian greyhounds, and the Shiba Inu.

The size of the breed appeared to contribute to this result; regardless of sex, large purebreds showed lower survival estimates than small—and medium-sized breeds, presenting a 1.17-1.28 faster time to death.

Some significant interactions between size and cephalic index were noted; brachycephalic-large and brachycephalic-medium dogs showed a 1.92-2.69 faster time to death than dolichocephalic breeds.

Phylogenetic analyses showed that median lifespan distribution showed strong links to evolutionary history, with breeds within a clade having lifespans closer to each other than would be predicted by chance alone.

Conclusions

Previous research suggested that purebreds appear to live significantly shorter lives than their crossbred counterparts, leading to the widespread belief that purebreds may be significantly less healthy than crossbreeds. However, this study presents a more nuanced picture indicating wide variability across breeds.

Further research is required across various geographies and environments; ideally, these analyses should include the cause of death for deceased dogs to identify factors that directly increase the risk of early death. Such explorations will strengthen veterinary knowledge about pure breeds and help their human companions care for them better.

Journal reference:

- Longevity of companion dog breeds: those at risk from early death. McMillan, K.M., Bielby, J., Williams, C.L., Upjohn, M.M., Casey, R.A., Christley, R.M. Scientific Reports (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-023-50458-w, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-50458-w