Given the understanding that excessive sugar consumption can lead to weight gain and obesity, the popularity and use of artificial sweeteners, which have significantly lower calories than sucrose and other conventional sugars but are substantially sweeter, has increased drastically in recent times.

The health and food safety agency in Europe has approved the use of certain artificial sweeteners in beverages, preserved foods, and desserts. Artificial sweeteners are also widely used in low-calorie food and drinks. However, growing evidence suggests that artificial sweeteners could be potentially harmful, with concerns about an increased risk of type 2 diabetes and obesity and possible carcinogenetic effects.

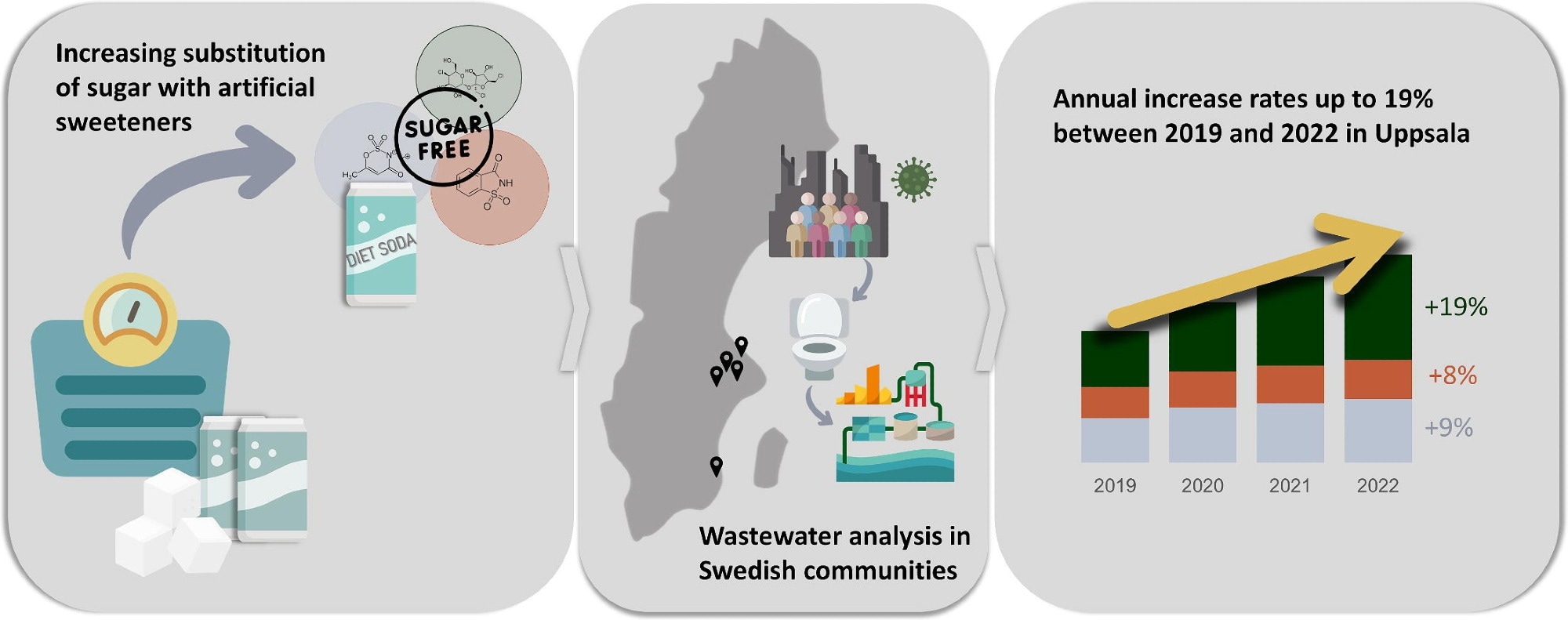

Hitherto, artificial sweetener consumption has been monitored primarily through manufacturing information, sales data, and population-based surveys, which present the risk of over- or under-estimation. Epidemiology using wastewater analysis is effective in determining the usage and exposure to various substances.

Graphical abstract

Graphical abstract

About the study

In the present study, the researchers used wastewater analysis to evaluate the temporal use of three artificial sweeteners — saccharin, sucralose, and acesulfame — in five different populations across Sweden and whether the restrictions implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic influenced the consumption of artificial sweeteners in these populations. Additionally, the study aimed to determine whether the artificial sweetener exposure levels, as determined by the wastewater analysis, could pose any health risks.

The researchers focused on the period spanning the COVID-19 pandemic because various other studies had reported that the restrictions associated with disease mitigation during the pandemic had a significant negative impact on people's mental and physical health, resulting in behavioral changes such as increased consumption of sugary foods and lower social interactions and physical activity levels.

The researchers collected wastewater samples from wastewater treatment plants from Enköping, Kalmar, Knivsta, Östhammar, and Uppsala using flow-dependent sampling. For some of the populations, samples were collected over two years. A total of 180 wastewater samples and 14 samples collected from Uppsala during the pre-pandemic period were analyzed.

The wastewater samples were analyzed using a combination of ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry. Chemical separation and quantification were carried out, and the method quantification and method detection limits were calculated.

Isotopically labeled internal standards, as well as native standards, were used for quality assurance and to monitor potential contaminations. Measures such as the daily mass load per thousand individuals and the sucrose equivalent dose were calculated to account for differences in sweetness among the three artificial sweeteners.

Population-normalized figures were determined to account for the possible direct disposal of artificial sweeteners into the sewage. Additionally, the usage trends of the three artificial sweeteners in Uppsala between 2019 and 2022 were calculated using a regression model.

Results

The study found significant differences in the use of the three artificial sweeteners among the five Swedish communities examined. Kalmar, in the southern region of Sweden, showed a higher usage of sucralose, while Östhammar and Enköping in central Sweden used saccharin and acesulfame more.

The sucrose equivalent dose values showed that the artificial sweeter use consistently showed a prevalence pattern of sucralose use greater than that of acesulfame or saccharin in all five communities. Acesulfame was the second most prevalently used artificial sweetener.

The monitoring periods for all the communities, excluding Uppsala, were short; therefore, no apparent trends in usage change were noticed. However, the four-year-long monitoring data from Uppsala revealed an approximately 19% increase every year in the use of sucralose, while the annual increases in the use of saccharin and acesulfame were 8% and 9%, respectively.

No delayed or immediate effects were observed in the artificial sweeter levels due to the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings indicated that the stress associated with COVID-19 and associated restrictions did not increase the consumption of foods and beverages containing artificial sweeteners among the populations of these five Swedish communities.

Furthermore, although only the consumption levels of acesulfame were substantially lower in the recommended range, none of the artificial sweeter consumption levels were found to be above the recommended threshold for daily intake, suggesting that these consumption levels did not pose any health risks.

Conclusions

Overall, the study showed that wastewater analysis for determining artificial sweetener consumption levels is a valuable tool to complement the survey results, which can sometimes be unreliable. The findings indicated that the consumption levels of three commonly used artificial sweeteners among five Swedish populations were within the recommended levels and did not pose any significant health risks.

Journal reference:

- Haalck, I., Székely, A., Ramne, S., Sonestedt, E., Brömssen, von, Eriksson, E., & Lai, F. Y. (2024). Are we using more sugar substitutes? Wastewater analysis reveals differences and rising trends in artificial sweetener usage among Swedish urban catchments. Environment International, 108814. DOI: 10.1016/j.envint.2024.108814, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412024004008