Behavioral science studies have found that individuals who belong to groups bonded by commonalities in language, country of origin, or political ideology are more cooperative with members of their group than strangers or members of other groups. This tendency, often referred to as parochialism or in-group favoritism, can be observed the world over. An inference from observations of in-group favoritism would be that members of a group would be more willing to compete with outsiders than with members of their group.

However, most evidence for in-group favoritism comes from studies that have not independently examined the effects of competition. People within a group are also more inclined to cooperate with in-group members while expending fewer resources when they can gain benefits that might come at a cost to others. Nonetheless, the absence of cooperation does not directly equate to the presence of competition, and cooperation within a group does not imply lower competition towards members of the group.

About the study

In the present study, the researchers aimed to understand whether in-group favoritism could be observed among participants from 51 countries during two scenarios of conflict—one in which the individual is the competitor (attacker) and the other in which the individual is on the defense, trying to prevent being outcompeted (defender).

For the first part of the study, the researchers obtained data from close to 13,000 participants from 51 countries, at the approximate rate of 250 individuals from each society. The participants were stratified by gender and age. An online survey was used to conduct the experiment, with the researchers designing the survey in English and providing professionally translated versions to the non-English speaking participants.

The experiment involved each participant facing randomly selected opponents from different countries and making 54 independent decisions about investing standardized monetary units (MU), with half of the decisions being made as the attacker and the other half as the defender.

The individual was informed about the opponent’s nationality just before they made the decision. For each block of 27 decisions, one involved an interaction with an opponent of the same nationality, one was with an unidentified individual, and the remaining 25 were with individuals of different nationalities.

For the second part of the study, the same experiment was conducted among 552 participants residing in Nairobi, Kenya, but belonging to different ethnocultural groups. This part of the study was to study interactions that could be generalized beyond the online interactions seen between individuals of different countries.

Kenya was chosen as the location for this part of the study because of its history of interethnic armed conflict, which is believed to have political roots. The researchers examined interactions between two communities with a history of conflict, such as the Kikuyu and Luo, as well as two communities that have been at peace with each other, such as the Luhaya and Kamba.

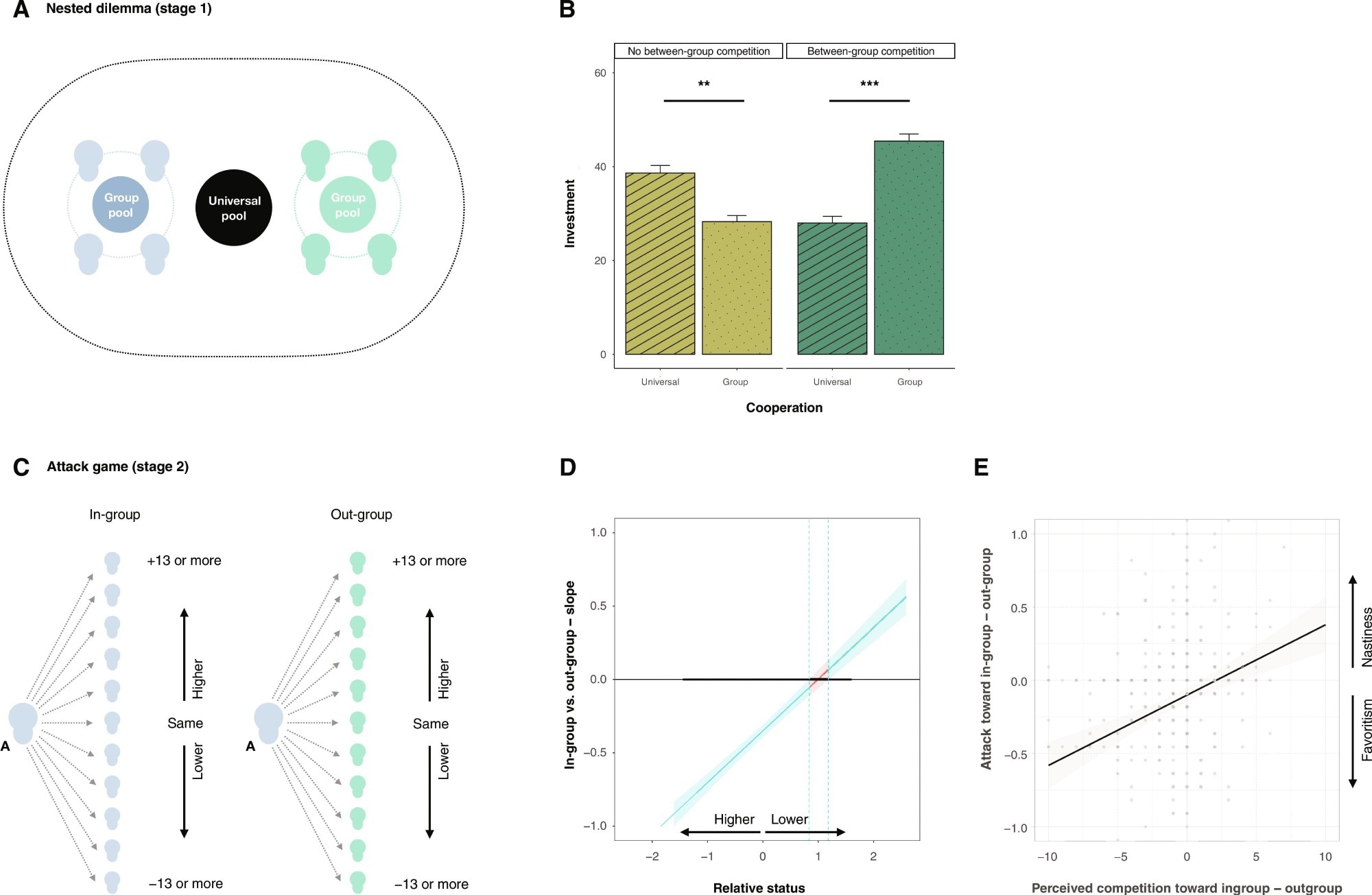

In-group cooperators and nasty neighbors in minimal groups. (A and C) Experimental setup of the nested social dilemma (top; stage 1, A) with an attack option (bottom; stage 2, C). (B) Between-group competition favors the emergence of in-group favoritism. Bar chart showing in-group favoritism and universal cooperation as mean percentage of the endowment contributed when competition is absent versus present. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (D) Status differences favor the emergence of within-group nastiness. Floodlight plot showing the regions of differences in status of the target of attack (x axis, standardized) for which the effect of in-group versus out-group (y axis) on attack becomes significant. The vertical lines in the floodlight plot show the exact values at which significance begins and ends. Blue lines indicate significance at 5% level. (E) Relative differences in perceived competition favor the emergence of a nasty neighbor effect. Scatterplot shows the association between perceived competition toward in-group members (minus out-group) and the nasty neighbor effect (i.e., attack of in-group members minus out-group members).

Major findings

The study found that while individuals of a group tend to cooperate with and trust members of their group, they also exhibit a tendency to compete, investing more in competing with in-group members than outsiders.

The researchers called this behavior the ‘nasty neighbor effect’ and found that individuals exhibited this behavior in situations involving investments in the attacker-defender contest. Additionally, a significant proportion of the participants also exhibited the ‘nasty neighbor effect’ in situations involving the prisoner’s dilemma game theory, where two individuals can cooperate for a mutual benefit, or one individual betrays the other for an individual reward.

The study found cultural variations in the ‘nasty neighbor effect’, correlating with egalitarian and hierarchical values, as well as with wealth. The researchers also discussed how the ‘nasty neighbor effect’ is not restricted to human societies and has been observed in other species, such as birds that live in groups or colonies, social insects, black-crested gibbons, Eurasian beavers, Diana monkeys, and banded mongoose, suggesting that this behavior might have evolutionary roots.

Conclusions

Overall, the findings indicate that in-group favoritism is not universally pervasive and that while cooperation with in-group members is largely beneficial, an individual might independently exhibit competitive behavior with in-group members in specific contexts. This ‘nasty neighbor’ behavior is independent of the cooperation and trust within groups and often emerges in situations of resource scarcity.