What matters more for heart health: sidewalks and green spaces or how we feel about them? New research suggests perception of walkability plays a crucial role in cardiovascular risk.

Sint Servaasbrug, historical footbridge crossing Meuse River, and background of cityscape in Maastricht, Netherlands. Study: The association of neighborhood walkability and food environment with incident cardiovascular disease in The Maastricht Study. Image Credit: Peeradontax / Shutterstock

Sint Servaasbrug, historical footbridge crossing Meuse River, and background of cityscape in Maastricht, Netherlands. Study: The association of neighborhood walkability and food environment with incident cardiovascular disease in The Maastricht Study. Image Credit: Peeradontax / Shutterstock

In a recent article in the journal Health & Place, researchers explored the influence of food environment and neighborhood walkability on the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in the Netherlands.

Their findings indicate that individuals in the neighborhoods perceived as most walkable, but not those with healthier food environments, experienced the lowest CVD risk. This research has implications for neighborhood design that promotes health and equity by considering residents' lived experiences and addressing disparities in underserved communities.

Background

Approximately 32% of global deaths and half of those in Europe are caused by CVD, though it is a non-communicable and preventable condition. Healthy lifestyle habits, including regular exercise and diets high in vegetables and fruit, significantly reduce the risk of CVD.

However, individuals living in walkable neighborhoods (characterized by higher sidewalk densities, more green space, and mixed housing and retail) have the opportunity to engage in physical activity, while access to healthy food options is conducive to a better diet.

Perceptions about built environments play an important role, as residents may not be aware that they have access to these facilities or may face barriers like poor sidewalk maintenance or safety concerns. Perceived walkability may better reflect usability factors such as aesthetics, safety, or connectivity that objective indices do not capture.

Previous studies suggest that higher walkability is linked to decreased rates of arterial stiffness, obesity, and hypertension, though one analysis found that walkability was correlated with higher blood pressure and triglycerides over time. Few studies have explored its impact on CVD, and those generally produced inconclusive evidence.

About the Study

This study utilized data from The Maastricht Study, a population-based cohort study in the Netherlands that focuses on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) and CVD. Participants aged 40-75 were recruited through media campaigns and registries, with an oversampling of individuals with T2DM.

Of the initial 9,188 participants, 6,117 were eligible for analysis after exclusions for missing data and CVD history. Neighborhood walkability and food environment data were integrated using Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Walkability was measured using a validated index based on factors such as population density, land-use mix, and public transportation access.

Walkability scores were assigned based on the year of enrolment (2012, 2015, 2019). Perceived walkability was assessed through the Abbreviated Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale (ANEWS). Food environment healthiness was measured using the Food Environment Healthiness Index (FEHI), incorporating food retailer density and nutritional quality.

CVD history was determined using self-reports and medical records, with new cases tracked annually through questionnaires and national mortality data. Researchers then used Cox regression models to investigate associations between CVD incidence and environmental exposures, adjusting for T2DM status, sex, age, and education. Sensitivity analyses tested alternative buffer sizes and sociodemographic interactions.

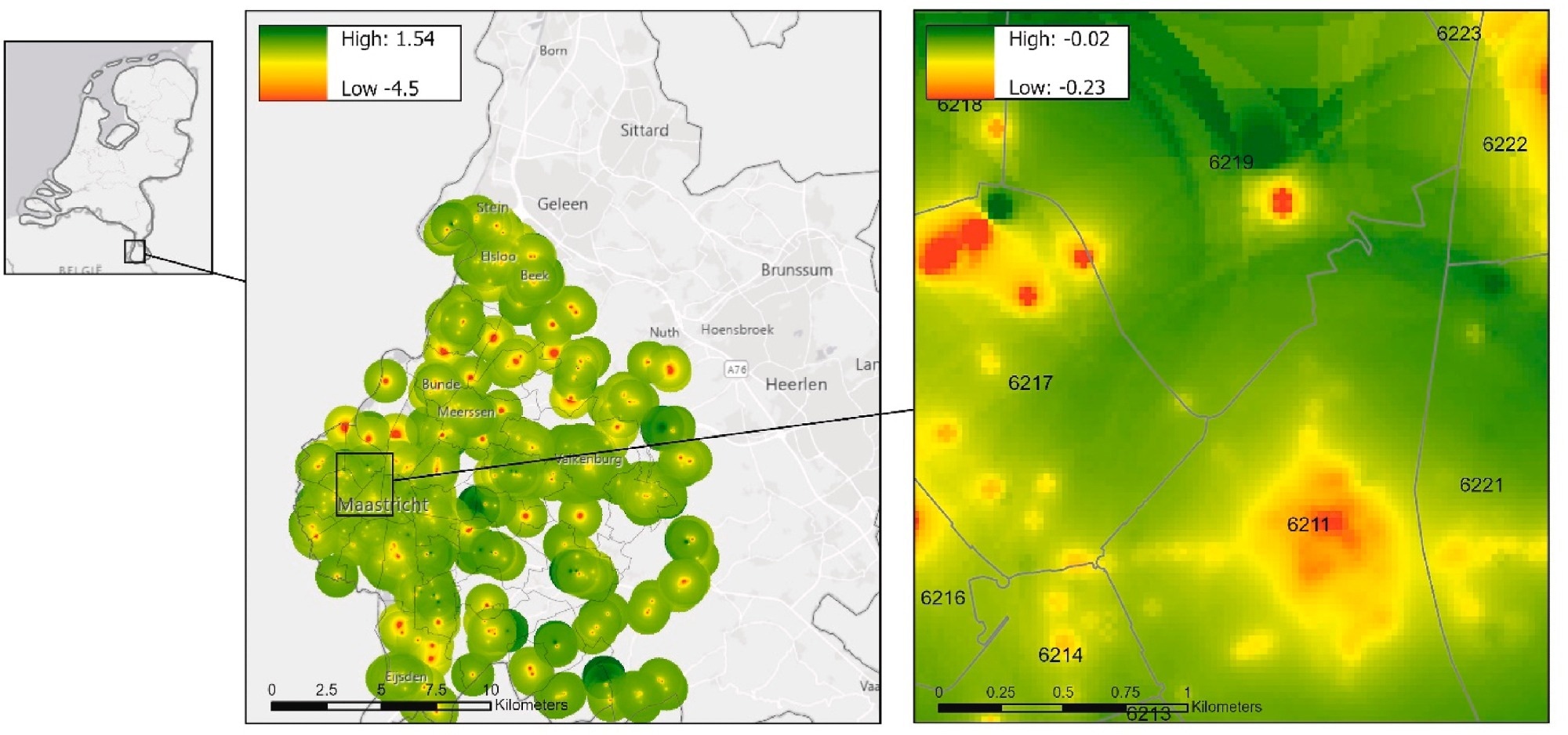

Greater Maastricht study region with Food Environment Healthiness Index heatmap. Green represents areas with healthier food retailers and red with less healthy food.

Greater Maastricht study region with Food Environment Healthiness Index heatmap. Green represents areas with healthier food retailers and red with less healthy food.

Findings

The participants were 59.8 years old on average; 52.2% were female. Higher education levels were associated with residence in more walkable neighborhoods, with 27.7% of the most educated group living in the highest walkability areas and 19.4% in the least educated group.

Similarly, a greater proportion of highly educated individuals resided in healthier food environments (26.3% vs. 21.3%). Additionally, a higher percentage of individuals with T2DM lived in the least healthy food environments (27.6%) compared to those without diabetes (23.9%).

Over a median follow-up of 7.2 years, 713 CVD events (586 non-fatal and 127 fatal) were recorded. Higher perceived neighborhood walkability was linked to a lower incidence of CVD.

In fully adjusted models accounting for age, sex, education, and T2DM, participants in the most walkable areas had a 23% lower risk of CVD compared to those in the least walkable areas. However, the objective walkability index showed no significant association with CVD risk.

While an initially observed association suggested that a healthier food environment reduced CVD incidence, this relationship remained insignificant after full statistical adjustments —a finding the authors hypothesize could reflect participants shopping for food outside their immediate neighborhoods. Sensitivity analyses using alternative buffer sizes showed no significant findings.

Interaction analyses revealed that women and individuals with lower education benefited most from living in walkable neighborhoods, suggesting walkable environments may help reduce health disparities in lower-SES groups. Those with the lowest education levels also experienced greater advantages from residing in healthier food environments.

Conclusions

The study found that higher perceived walkability was linked to lower CVD risk, but objective walkability measures and food environments were not associated with CVD incidence.

This suggests that individuals' perceptions may better capture neighborhood features like usability, safety, and aesthetics that influence health. However, limitations include the relatively short follow-up period, potential environmental changes over time, and measurement constraints.

Future research should refine walkability metrics, track environmental changes, and explore additional social and built environment factors affecting CVD risk, with attention to populations disproportionately affected by CVD, such as those with lower education levels.

Journal reference:

- The association of neighborhood walkability and food environment with incident cardiovascular disease in The Maastricht Study. Chan, J.A., Meisters, R., Lakerveld, J., Schram, M.T., Bosma, H., Koster, A. Health & Place (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2025.103432, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1353829225000218