Subsequently, they propose a systematic and iterative approach to addressing present limitations, leveraging in silico, ex vivo, in vitro, and in vivo datasets in combination with traditional microbiological techniques as the first step in realizing the transition from microbiome theory to beneficial clinical outcomes.

Notably, they emphasize that this process should involve repeated testing and refining of hypotheses, moving back and forth between different experimental models when necessary to ensure robust results that can translate to human health applications.

Background

Many studies have examined the relationship between human microbiota and their hosts, finding the former responsible for several indispensable functions ranging from the obvious (e.g., digestion) to the unexpected (e.g., neurotransmitter secretion). Human microbiome assemblages are almost unique, shaped by a combination of parental, environmental, genetic, and behavioral factors, with the microbiome's health directly correlating with their hosts' health.

Notably, disturbances to typical microbiome composition and abundance (termed "dysbiosis") have frequently been found to correlate with increased risk of obesity, cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), gestational diabetes, cancers, and Parkinson's disease. Unfortunately, a routine refrain in all forms of science, from basic statistics to advanced studies, is that "correlation is not causation" – we still are unaware if dysbiosis is the cause of, or the result of, these diseases.

"...despite the high number of pertinent studies, a well-defined microbial signature has not yet been identified in patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and it is not yet clear whether shifts from a healthy microbiota depend on the disease itself or on confounders, such as exclusion diets, drugs, or impairment in gastrointestinal (GI) motility."

A similar dearth of causational evidence exists across microbiome research, sometimes severely hampering clinical interventions. An ideal example of these pitfalls is that of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) therapy – while fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) and probiotics are assumed to improve IBS outcomes, their mechanisms and the roles of microbiome modulation in these interventions remain poorly understood.

About the perspective

The present perspective aims to synthesize current knowledge in microbiome research, focusing on the limitations and gaps in the literature. It touches upon novel advances in research methodologies and technologies. It highlights how these advances can help transition microbiome research from the bench (theory) to the bedside (clinical trials and application). Crucially, it stresses the need for careful experimental design and iterative validation to avoid overinterpreting correlative findings. Finally, it provides recommendations for future studies to help facilitate this transition, allowing for a healthier and more knowledgeable tomorrow.

Traditional (associative) microbiome research – strengths, advancements, and limitations

Microbiome research is still rather young, having only begun in its current state about a decade ago. Sequencing technologies were still developing back then, and even the most cutting-edge studies only utilized small datasets and single-center cohorts, allowing for limited taxonomic profiling and almost no generalizability. Consequently, most of our current microbiome knowledge is based on correlative investigations.

Since then, however, sequencing technologies have advanced at unprecedented rates. Current whole-genome shotgun sequencing (WGS) allows for thousands of times more resolution (strain-level resolution) and substantially larger datasets than previously possible at a fraction of the price. This has, in turn, fostered collaborations between researchers, thereby substantially improving the generalizability of results.

Similar advances in multi-omics (metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics) allow for individual-level profiling, which, when shared on a global scale, enables a deeper biological understanding of the role of microbial communities in shaping human health. Parallel advances in computational power and the advent and development of machine learning (ML) algorithms have further helped unravel previously invisible patterns between host and microbiome traits.

"Now, instead of focusing on a single patient phenotype compared with a healthy control, researchers can mine data from large cohorts to evaluate the robustness and reproducibility of findings across populations, as well as their specificity for a certain disease, rather than just observing differences when compared to healthy controls."

Unfortunately, these advances, while undeniable, do not overcome the lack of direct proof of causality between hypothesized microbiome aspects and reproducible clinical outcomes. Furthermore, most associative studies are at high risk of observation misinterpretation or overestimation, failing to accurately identify the roles of various microbial strains within a study population. Additional methodological challenges, such as the predominant use of fecal samples (which may not represent mucosal microbiota), geographic variability in microbiome profiles, and difficulties distinguishing live from dead microbes in sequencing data, further complicate interpretations.

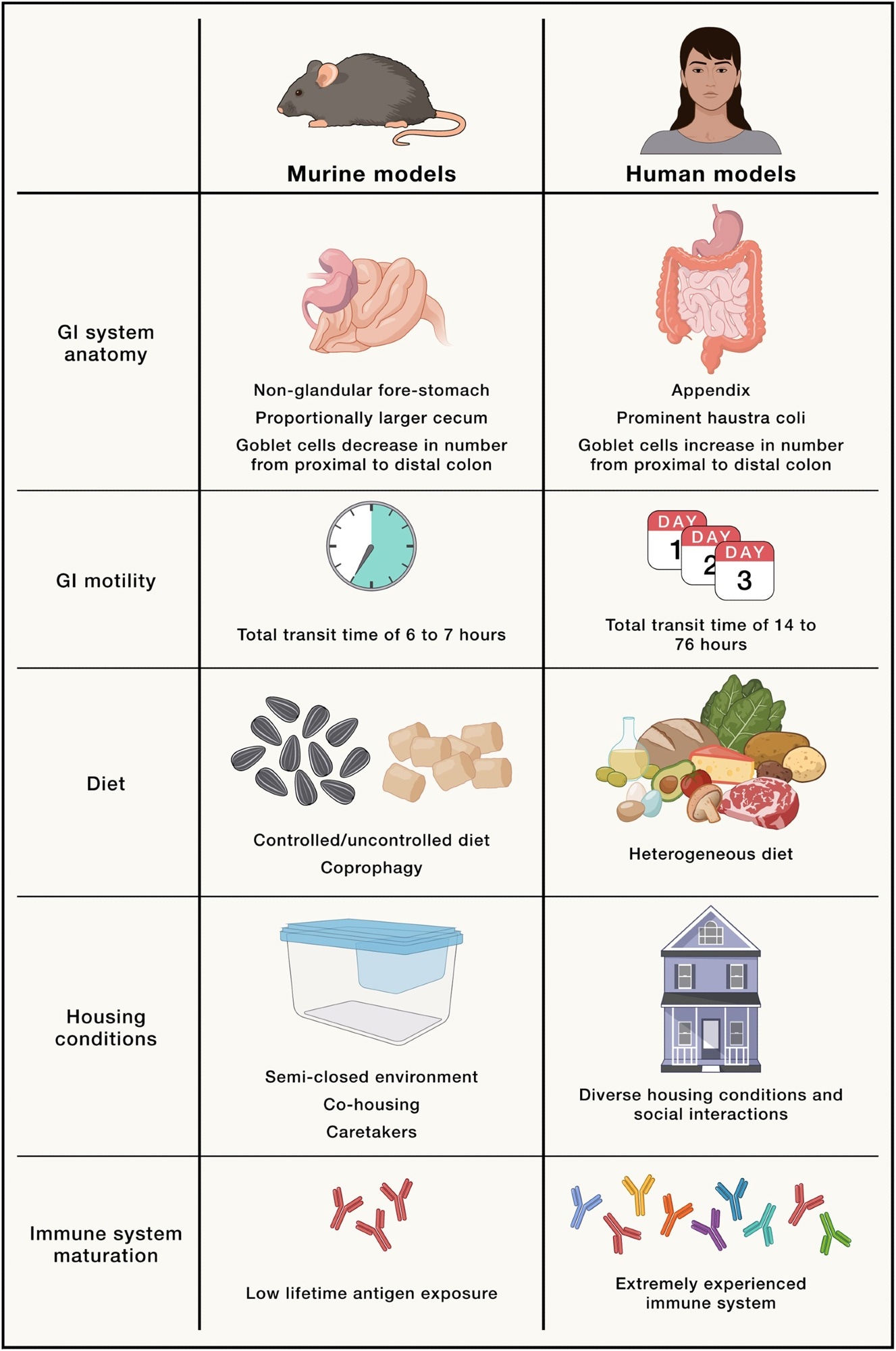

Physiological, environmental, and biological differences between murine models and humans, which could explain difficulty in translating microbiota research from animals to the clinic

The solution? Preclinical trials

Preclinical trials utilizing host-centric or microbe-centric model systems present a robust platform for proving causation. They have previously been used across medicine and science to elucidate the mechanisms underpinning several diseases, including cancers and immune-mediated disorders, resulting in the development and validation of clinically beneficial drugs and therapeutics.

Host-centric methods such as in vitro models (cell lines, organoids), ex vivo ('organ-on-a-chip') models, and in vivo animal models can help establish causation at varying degrees of system complexity. Subsequently, microbe-centric culturing experiments, monocolonization, labeling experiments, and Drosophila ("fly as a petri dish") models can help unravel the mechanistic underpinnings of host-microbiome interactions.

Notably, these preclinical trials would build upon the theoretical framework of correlation/associative studies, allowing for a safe transition toward clinical application (interventions, drug discovery, and treatments).

However, the authors caution that translating findings from animal models to humans remains challenging. Anatomical, physiological, and immunological differences between species — including gut structure, microbiome composition, and metabolism — can hinder the applicability of preclinical results.

"These models provide crucial insights into the complex interactions among different microbial communities and between them and the host physiology, and help optimize artificial microbiome therapeutics at several levels, accelerating the translation of clinically relevant discoveries into effective future microbiome therapeutics and paving the way for groundbreaking advancements in human health and disease management."

Journal reference:

- Turjeman, S., Rozera, T., Elinav, E., Ianiro, G., & Koren, O. (2025). From big data and experimental models to clinical trials: Iterative strategies in microbiome research. In Cell (Vol. 188, Issue 5, pp. 1178–1197). Elsevier BV, DOI – 10.1016/j.cell.2025.01.038, https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(25)00107-2