New analysis shows that pairing a low-sodium diet with DASH eating habits reduces cardiovascular risk by over 14%, with the biggest wins for women and Black adults facing high blood pressure.

Study: Dietary sodium reduction lowers 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score: Results from the DASH-sodium trial. Image Credit: New Africa / Shutterstock

Study: Dietary sodium reduction lowers 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score: Results from the DASH-sodium trial. Image Credit: New Africa / Shutterstock

In a recent article published in the American Journal of Preventive Cardiology, researchers used data collected in the United States to investigate how reducing sodium in the diet, either in isolation or while following the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, affects the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) over 10 years.

Their findings indicate that adherence to DASH dietary patterns and reducing dietary sodium independently reduced the risk of ASCVD, with the greatest benefits observed when the two interventions were combined.

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading global cause of mortality, but over half of the cases are linked to modifiable lifestyle factors such as physical activity and diet. Across the U.S., unhealthy dietary habits, particularly excessive sodium intake, which more than 90% of American adults exceed, are major contributors to poor cardiovascular health.

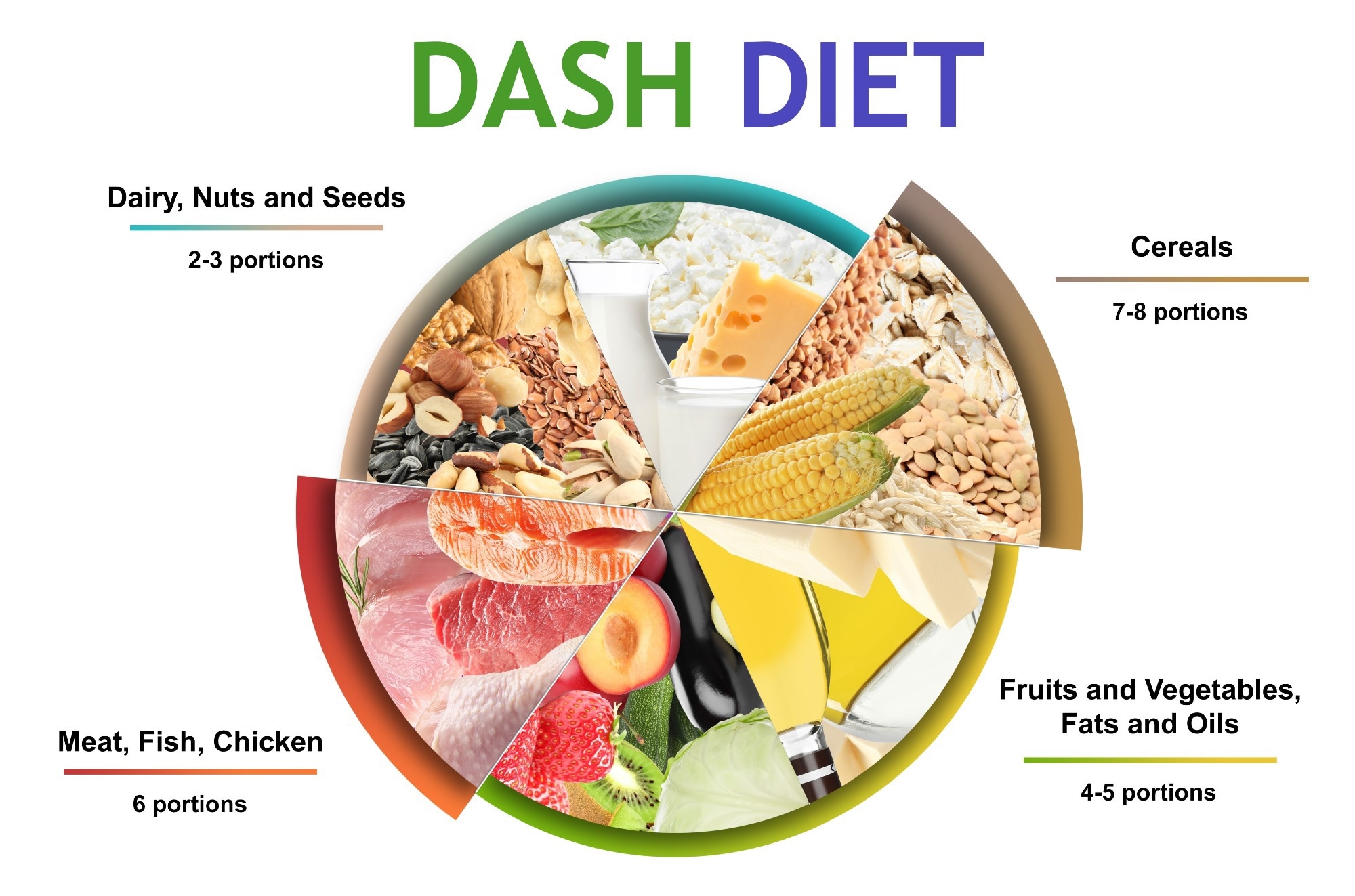

The DASH diet, which is endorsed by national recommendations, encourages the intake of low-fat dairy, whole grains, vegetables, and fruits while reducing the consumption of added sugars, cholesterol, and saturated fats. It has been associated with lower CVD incidence, reduced cardiac injury, and decreased 10-year ASCVD risk.

While a previous trial called DASH-Sodium showed that both the DASH diet and sodium reduction were effective in improving blood pressure, their effects on the long-term risk of ASCVD were not analyzed.

About the study

In this study, researchers conducted a secondary analysis using data collected during the DASH-Sodium project to evaluate whether reducing sodium intake, alone or alongside the DASH diet, could lower the risk of ASCVD over ten years.

The researchers hypothesized that decreasing sodium consumption would reduce risk alone and that combining it with DASH dietary approaches would have an additive effect.

The DASH-Sodium project was a randomized, multi-center feeding study conducted between 1997 and 1999 in four U.S. clinical sites. It enrolled adults with elevated blood pressure who were at least 22 years old, while excluding those with insulin-dependent diabetes, heart disease, renal insufficiency, poorly controlled dyslipidemia, excessive alcohol intake, or those on antihypertensive medications. Participants were randomized to follow the DASH diet or an average American diet over 12 weeks. Each participant consumed three sodium levels—high, meaning 1.6 mg of sodium for each kilocalorie consumed (about 3,500 mg/day for a 2,000 kcal diet), medium (1.1 mg per kilocalorie, about 2,400 mg/day), or low (0.5 mg per kilocalorie, about 1,150 mg/day)—in random order. Each sodium level was consumed for about 30 days, with washout periods in between.

The study provided all meals, ensuring consistent nutrient intake. The highest sodium intake represented typical American consumption, while the medium matched guideline limits, and the lowest level was below the recommended intake.

The primary outcome was the ASCVD risk score over ten years, calculated using the Pooled Cohort Equation (PCE). Static risk factors like age and smoking were measured at baseline, while dynamic variables such as blood pressure and cholesterol were measured after each period of feeding.

Blood samples and blood pressure readings were collected using standardized methods. Data were analyzed using mixed effects models, accounting for repeated measures. Sensitivity analyses addressed participants outside the PCE’s valid range by imputing or excluding out-of-range values. Stratified analyses assessed outcomes by age, sex, race, hypertension status, obesity, and smoking.

It is important to note that each sodium intervention period lasted only 30 days. While this allowed for controlled measurement of short-term changes in ASCVD risk scores, it does not provide evidence about the long-term impact of sustained dietary changes.

Findings

Among 390 participants, baseline characteristics were similar across the control and DASH diet groups. The DASH diet led to a greater reduction in the estimated ASCVD risk over ten years compared to the control diet, with an absolute difference of −0.12% and a relative difference of −5.33%.

Sodium reduction further decreased ASCVD risk, with low sodium intake showing greater risk reductions than medium or high sodium intake. Combined DASH diet and low sodium intake resulted in the largest decrease in ASCVD risk, with an absolute difference of −0.35%, and a relative difference of −14.09% compared to the control diet, which was high in sodium.

Stratified analysis showed stronger sodium reduction effects in women, Black adults, and those with stage 2 hypertension, while no significant differences were seen by age, obesity, or smoking status. Sensitivity analyses supported these findings.

The study also noted that race was dichotomized as Black versus non-Black, so effects among other minoritized groups could not be determined.

Conclusions

The DASH diet significantly lowered the estimated 10-year ASCVD risk compared to a typical American diet. Sodium reduction further reduced risk, especially when combined with the DASH diet, with greater benefits among women, Black adults, and those with stage 2 hypertension.

These results align with previous evidence supporting DASH and sodium reduction for cardiovascular health. However, no long-term randomized trials have confirmed DASH’s effect on actual CVD events, as most evidence is based on risk factor and risk score reduction, not direct clinical outcomes. The optimal sodium intake level also remains debated.

Nevertheless, even moderate sodium reductions appeared beneficial, reinforcing public health efforts to reduce sodium intake. The authors note that the study’s exclusion criteria (such as individuals with existing heart disease, diabetes, or those on antihypertensive drugs) and the relatively short intervention periods may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research should focus on long-term outcomes, include a broader range of participants, and further refine sodium intake guidelines.

Journal reference:

- Dietary sodium reduction lowers 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score: Results from the DASH-sodium trial. Knauss, H.M., Kovell, L.C., Miller, E.R., Appel, L.J., Mukamal, K.J., Plante, T.B., Juraschek, S.P. American Journal of Preventive Cardiology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.ajpc.2025.100980, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666667725000522?via%3Dihub