Sponsored Content by Bruker BioAFMReviewed by Emily MageeMar 27 2025

In this interview with News Medical Life Sciences, Prof. Dr. Kristina Kusche-Vihrog, head of the Institute of Physiology at the University of Lübeck, speaks about the nanomechanics of living cells and their implications for cardiovascular disease.

Could you start by introducing our readers to your research into endothelial cells and what role these cells play?

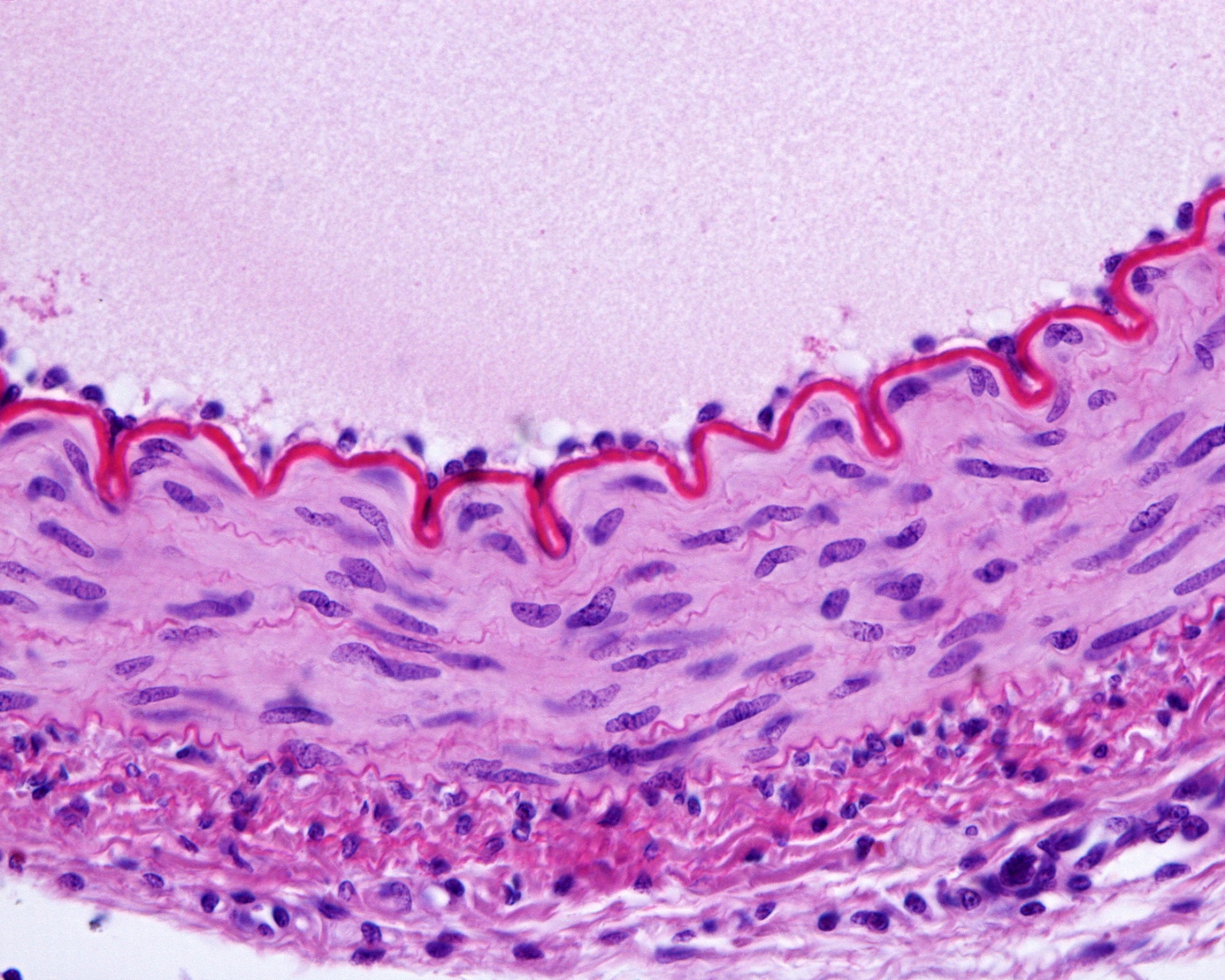

I started a research project as a postdoc, looking into the role of epithelial cells. As this work developed, we recognized that the endothelial cells lining the inside of blood vessels also greatly impact the vascular system. These cells carry a lot of ion channels in their plasma membranes and are highly flexible, meaning that they can react to the force of the streaming blood.

Their position inside of the blood vessel is important because endothelial cells can sense everything that comes with the blood, allowing them to react accordingly. For example, endothelial cells could sense vasoactive factors and provide signals to the vascular smooth muscle cells surrounding them.

These cells can also be deformed by forces exerted by streaming blood. When deformed, they react in a certain manner, resulting in vasodilating or vasoconstrictory factors that help regulate the vasculature.

We recognized that this cell behavior is especially important in terms of passive physiology. Because they are flexible and deformable, endothelial cells can switch between different mechanical states. They typically exhibit normal and healthy behavior, but when something happens in the body, like disease or inflammation, the cells change their behavior and mechanical properties. This is known as endothelial dysfunction.

Image Credit: Jose Luis Calvo/Shutterstock.com

What impact do cell stiffness and cells’ mechanical properties have on the body? How do we measure these characteristics?

An enzyme called the eNOS (endothelial nitric oxide synthase) is found underneath the plasma membrane. This enzyme was discovered many years ago. When cells are soft and deformable, their cytoskeleton is depolymerized.

Streaming blood can activate this enzyme, prompting a cascade of arginine and other substances. NO is produced by endothelial cells as a response to this deformation from the bloodstream, causing an increase in vessel diameter and, in turn, a decrease in blood pressure.

This important mechanism is connected to the cell’s surface, which is 150 to 200 nanometers of the outer cell layer. The glycocalyx is located on top of the plasma membrane; the layer underneath the plasma membrane is called the cortical cytoskeleton.

What role does the glycocalyx play in endothelial cells and cell stiffness? How is this typically measured?

The glycocalyx is a fascinating structure, and one of the most important factors in endothelial function is the integrity of the glycocalyx.

An AFM is the perfect instrument for measuring the glycocalyx. We can use the AFM to measure this by touching the glycocalyx with a small, 1-micrometer spherical tip and with very low loading force in the range of 0.5 nanonewtons.

The glycocalyx structure is highly flexible and vulnerable, so we cannot use high-loading forces. The first few nanometers of the indented cell make up the glycocalyx; as we indent more, we touch the surface of the endothelial cell, the plasma membrane, and the underlying cortical cytoskeleton.

The resulting AFM curve features several slopes and can take weeks to analyze. We were able to use enzymes like heparinase to remove the glycocalyx enzymatically, allowing us to quantify the height and mechanical properties of the glycocalyx and the mechanical properties of the cell cortex.

The glycocalyx has a mesh-like structure built on many factors of glycoproteins and proteoglycans. For example, heparan sulfate is an important compound of the glycocalyx. the glycocalyx builds a vascular protective structure on top of the cells. Quantifying this can be challenging, but the AFM is ideally suited to this task.

Conversations on AFM #3: Insights of a Scientist, NanoMechanics in Living Cells

Video Credit: Bruker BioAFM

Are your experiments performed in cell culture, and what types of cells do you normally work with?

We use several different models. HUVECs are our gold standard, and we freshly isolate these from the umbilical vein here, after sourcing cells from the hospital at the University of Lübeck.

These cells pose a challenge when transfected; for example, we may use CRISPR-Cas to knock out specific channels in the cell.

I prefer to work ex vivo, using blood vessels from mice or patients and splitting them open so that the endothelial cells face upwards. This allows us to measure these endothelial cells in ex vivo blood vessels. This is ideal because we can use patient vessels or different mouse models, including transgenic mouse cells.

Glycocalyx preparation takes time when culturing the endothelial cells. This is often a problem at other labs that culture their endothelial cells for only two days, for example, because this is not long enough for proper glycocalyx preparation.

Cells in culture and ex vivo preparation patches need time, at least three to four times until the glycocalyx is recovered and can be measured.

High blood pressure is probably the most well-known vascular disease, with around 50% of adults thought to have hypertension, according to the CDC. Hypertension causes increased cell stiffness in blood vessels, which can lead to inflammation and secondary issues. How do you see your work directly translating to medical research, for example, with hypertension?

Endothelial stiffness can be directly correlated to arterial stiffness. We determined this via a project where we worked with different patient cohorts. To measure this, we used standardized HUVECs and incubated these with patient serum, including pathologic compounds.

We found that factors in the patient serum seriously damaged the glycocalyx and stiffened the cell cortex. This stiff cell cortex could be correlated to arterial stiffness measured as pulse wave velocity.

Our findings at the single-cell level were also true for significant parts of the arterial system. We found local vasoconstriction, for example, but in the case of inflammatory disease, I am convinced that endothelial cell behavior impacts the arterial system.

Could you also share some insight from your research on systemic sclerosis and cell stiffness and the global components that you think play a role in these?

This work is an ongoing project, and we currently have preliminary data, particularly on autoantibodies like those associated with SARS‑CoV‑2.

Inflammatory disease results in the body producing more autoantibodies, though this process can be a ‘black box.’ These autoantibodies bind against, for example, G protein-coupled receptors like angiotensin II receptors, completely changing the endothelial surface.

As part of this process, the glycocalyx is damaged, with its height flattened completely. This is essentially a shedding of the glycocalyx and a stiffer cortex. Our working hypothesis is that in inflammatory diseases like systemic sclerosis, we see the body's self-reaction, and when these autoantibodies bind to these receptors, we see specific cascades leading to inflammatory processes.

These receptors are all linked to the cortical cytoskeleton. This is a specific cytoskeleton underneath the plasma membrane. This is not the stress fibers inside the cell; rather, it is a very narrow compartment at around 200 nanometers from the top of the cell surface. This actin-myosin mesh features linker proteins and receptors, with the glycocalyx linked to actin via syndecan or perlecan.

Inflammatory diseases lead to shedding of the glycocalyx or cortical stiffening, caused by polymerization of the cortical actin and an intrinsic signal, which leads to collapse of the glycocalyx.

We can manipulate the actin cytoskeleton to investigate this, using fluorescence microscopy to focus on the cortical cytoskeleton. My research is focused on this cortical actin, so a confocal microscope is useful.

Manipulating the cortical cytoskeleton involves using jasplakinolide to polymerize the actin mesh, or we can use cytochalasin D to depolymerize it. Manipulating actin fibers underneath the plasma membrane results in reactions from the glycocalyx, with a stiff cortex leading to a collapse of the glycocalyx and a soft cortex giving an upright and proper glycocalyx.

What are some of the current challenges for this type of research?

My first AFM measurements using early instruments were challenging, but modern AFMs are much more user-friendly. The real challenge is working with these types of cells. It is imperative that we handle cells in a physiological way because they are living cells, and only a living cell in a perfect environment can properly act like a living cell.

For example, factors such as pH and salt content must be optimal, with appropriate growth time in every case. It is important to study the morphology and behavior of the endothelial cells before the experiment. A lot of experience working with cell culture experiments is needed to confirm that the cells are in good shape before experimenting.

Where do you think the future of AFM will lead, and what role will it play for scientists in the future?

AFM is one of the best methods for quantifying cell mechanics reliably. It allows me to view online how a living cell reacts when I apply substances. I would like to see more standardized measurements, meaning that we can use AFM as a diagnostic tool.

For example, chronic kidney disease patients often require biopsies in the kidney, which are painful. From my group's research, I know that when we use patient serum and incubate standardized HUVECs with this, we can differentiate between stage three, four, and five chronic kidney disease.

Using patient serum, we can see significant differences in cortical stiffness and glycocalyx height. This method is noninvasive, and while it takes time to create the necessary force curves, it would be useful to integrate the AFM as a diagnostic tool in translational projects and clinics.

We are not far from this reality. In our current project, for example, we can measure endothelial dysfunction. A stiff cell or a cell with a damaged glycocalyx are hallmarks of a dysfunctional cell. We can perform these diagnostics in lab projects, but clinicians are reluctant to use this approach at the moment because of the complexity of the machine involved.

I am trying to convince different groups to try this approach, with clinicians giving us serum and my team providing details on detected endothelial dysfunction.

About Prof. Dr. Kristina Kusche-Vihrog

Prof. Dr. Kristina Kusche-Vihrog is director of the Lübeck Institute of Physiology in Germany and on the board of the German Hypertension Foundation. In 2018, she received the German Society of Nephrology award for research into hypertension. Her research focuses, in particular, on the influence of inflammatory processes on endothelial dysfunction as a precursor to the development of cardiovascular diseases.