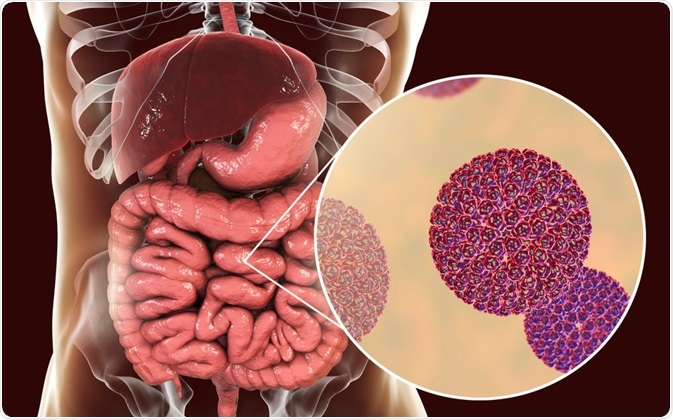

Rotavirus is the dominant cause of infant gastroenteritis worldwide and is associated with substantial mortality in developing countries. Despite its significant clinical importance, the pathophysiological mechanisms by which rotavirus induces fluid and electrolyte secretion are still not fully understood.

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock.com

It is fair to say that the outcome of intestinal infection with rotaviruses is more complex than initially thought, and it is largely affected by a complex interplay of both viral and host factors. Rotaviruses infect enterocytes in the villous epithelium of the small intestine, which is where replication occurs. Therefore, the early events in infection are mediated by virus-epithelial cell interactions.

The mechanism that causes vomiting, which is characteristic of the early illness, is poorly understood. It may be the result of delayed gastric emptying or early cytokine release acting centrally. The relative importance of extraintestinal replication and viremia is also not clear.

Pathogenesis of the infection

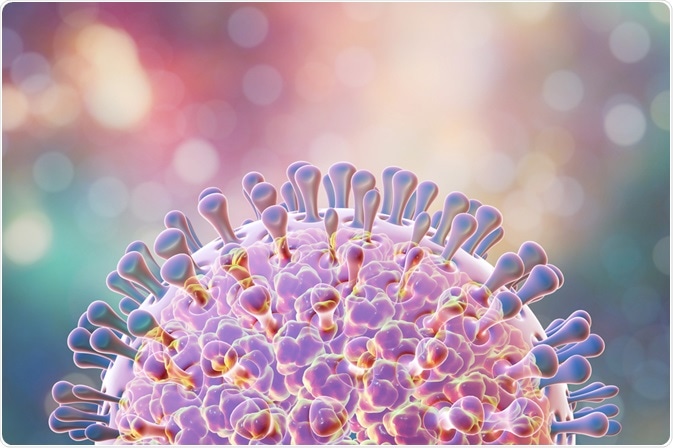

Studies of rotavirus infection of polarized intestinal epithelial cells demonstrate that these viruses infect cells differently, depending on whether or not they require sialic acid for initial binding, and the infection can alter epithelial cell functions. Upon binding, the virus enters human cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis and forms a vesicle known as an endosome.

Proteins in the outer layer of the virus, which are known as VP7 and VP4 spike, disrupt the membrane of the endosome, which creates a difference in calcium concentrations. This results in the breakdown of VP7 trimers into single protein subunits and the formation of a double-layered particle.

Image Credit: Kateryna Kon / Shutterstock.com

The eleven double-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) segments remain within the protection of the two protein shells. The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of the virus creates messenger RNA (mRNA) transcripts of the double-stranded viral genome. By remaining in the core, the viral RNA evades innate host immune responses through a process known as RNA interference that is triggered by the presence of double-stranded RNA.

Rotavirus infection alters the function of the small intestinal epithelium, resulting in diarrhea. The mechanism of diarrhea is multicomponent in nature and results from the direct effects of the virus infection itself, as well as the indirect effects of infection and the host response.

Therefore, diarrhea may be caused by several mechanisms, including malabsorption that occurs secondary to the destruction of enterocytes, villus ischemia, activation of the enteric nervous system, as well as intestinal secretion stimulated by the intracellular or extracellular action of the rotavirus non-structural protein NSP4.

The NSP4 protein of rotavirus, which has been described as the first viral enterotoxin, has a significant role in causing diarrhea. This enterotoxin induces diarrheal response, stimulates calcium-dependent cell permeability, and alters epithelial cell integrity.

Molecular and pathophysiological changes

One of the main effects of rotaviral infection is a decrease in intestinal disaccharidase activities with a relatively intact intestinal brush border membrane. NSP4 can specifically perturb the paracellular permeability to various molecules, reorganize filamentous actin filaments, and prevent transport of the Zona Occludens-1 (ZO-1) protein to tight junctions.

P70S6Kinase (p70S6K) belongs to the growth factor-regulated serine/threonine kinase family. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) has been shown to play a role in transducing extracellular signals into a cellular response. Phosphorylation of these kinases was found to be decreased in severe cases of rotavirus infected ileum.

Elevated levels of prostaglandin E2 production is observed in the rotavirus infected intestine, which can induce epithelial cell death. Furthermore, NSP4 was found to have toxin-like activity with the potential to upregulate nitric oxide synthase, resulting in peroxynitrite production and the inhibition of both cell migration and cell growth.

The end-result of rotavirus infection can be a decreased intestinal absorption of sodium, glucose, and water, as well as a reduction in the levels of intestinal lactase, sucrase activity, and alkaline phosphatase. Each of the aforementioned pathophysiological events can lead to isotonic diarrhea. Recovery from a first rotaviral infection does not usually lead to permanent immunity.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Apr 26, 2021