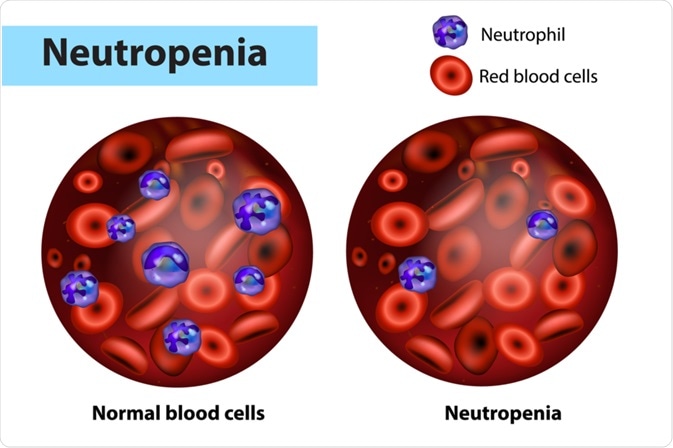

Neutropenia represents an abnormally low level of neutrophils in the blood. This condition can be graded as mild, moderate, and severe, corresponding respectively to absolute neutrophil count values of 1000–1500 cells/μL, 500–1000 cells/μL, and less than 500 cells/μL. Unraveling the cause of neutropenia is a complex diagnostic challenge; therefore, it is crucial to understand both the inherited and acquired types of the condition.

Image Credit: Sakurra / Shutterstock.com

Inherited neutropenia

The two main types of hereditary neutropenia are cyclic neutropenia, which is also known as cyclic hematopoiesis, and severe congenital neutropenia, which is inherited as an autosomal recessive condition and is sometimes referred to as Kostmann syndrome. Other conditions such as Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome type 2, Chediak-Higashi syndrome, Barth syndrome, Cohen syndrome, and Shwachman-Diamond Syndrome can also feature neutropenia as a component.

Cyclic neutropenia is characterized by an oscillation of peripheral blood neutrophil counts with an approximately 21-day frequency and neutropenia spanning 3 to 6 days. Life-threatening infections can follow neutropenic nadir of the cycle, with frequent aphthous gingivitis, periodontitis, oral ulcerations, fever, and occasional sepsis.

Autosomal dominant and sporadic cyclic neutropenia are attributable to heterozygous, germline mutations of the ELA2 gene encoding the neutrophil elastase, which has been demonstrated by genetic linkage analyses and positional cloning. One potential mechanism of the phenotypic effect of mutations in ELA2 is a decrease in self-renewal of the late granulocyte-monocyte progenitors and myeloblasts.

Kostmann was one of the first authors who described congenital agranulocytosis in a report of static neutropenia accompanied by an arrest at the promyelocyte stage of development in the bone marrow, with apparent autosomal recessive inheritance. However, this condition is genetically heterogeneous, often arising as a sporadic and lethal autosomal dominant disorder.

Patients with severe congenital neutropenia exhibit an increased risk of developing a myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). The consequence of AML has become more obvious as patients live longer with treatment using granulocyte-colony stimulating factors.

Acquired neutropenia

The most common underlying cause for mild and moderate acquired neutropenias is transient marrow suppression as a result of different viral infections. The most common culprit agents are respiratory syncytial viruses, influenza viruses, Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis, varicella, rubella, rubeola, and dengue virus.

A myriad of different drugs including antibiotics, anti-inflammatory agents, and anticonvulsants have been associated with neutropenia. Some drugs act as haptens that lead to antibody production against neutrophils, resulting in their destruction, whereas other drugs can accelerate the process of apoptosis or create circulating immune complexes.

Immune neutropenia results from antibodies that are directed against neutrophil-specific antigens. Alloimmune neonatal neutropenia is caused by maternal sensitization to fetal antigens not present on her own cells, resulting in a variety of antibodies that are passed via the placenta to the fetus. Primary autoimmune neutropenia is a rare disorder that arises when an infant or child forms antibodies directed against their own neutrophils.

On the other hand, secondary autoimmune neutropenia most often affects adults as a part of systemic autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, or systemic lupus erythematosus. Secondary autoimmune neutropenia can also arise in certain infections, namely parvovirus B19, human immunodeficiency virus, or Helicobacter pylori.

Impairment in DNA processing in both vitamin B12 and folic acid nutritional deficiencies may result in neutropenia, in addition to megaloblastic anemia. The mechanism of neutrophil nuclear maturation is impaired, which leads to hypersegmentation of the neutrophil nuclei and ineffective marrow proliferation and maturation. Treatment of this type of neutropenia is straightforward, as it simply involves the replacement of the deficient factor.

The enlargement of the spleen and hypersplenism from any cause can subsequently result in mild neutropenia due to sequestration. The idiopathic diagnosis of neutropenia can be considered when all known causes have been eliminated, albeit some of those patients can have immune neutropenia or familial benign neutropenia.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 23, 2023