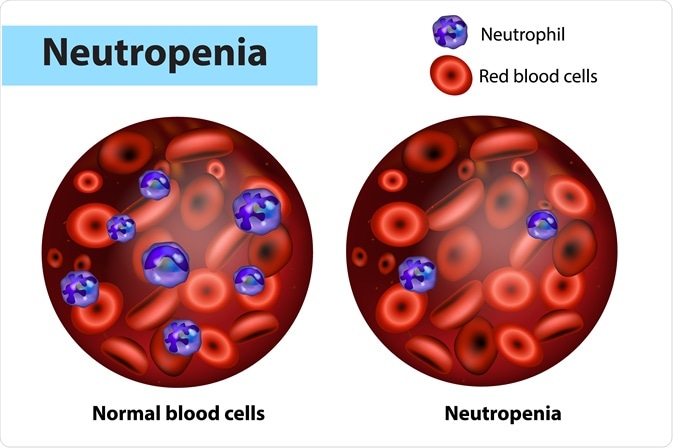

Neutropenia is a hematological disorder defined as a reduction in the absolute number of neutrophils in the blood. The most common causes of neutropenia are those that are acquired, including viral infections, neutropenia associated with different drugs and immune neutropenia.

Neutropenia is a rather frequent finding which is often well tolerated and normalizes rapidly but can also be a secondary finding in a patient with significant disorders, who may be at risk for infectious complications. The standard hematologic examination is cell counting under a microscope, which is necessary to confirm disorders identified by automated cell counters and to examine the cell morphology.

Image Credit: Sakurra/Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Sakurra/Shutterstock.com

Evaluation of the neutropenic patient

As is the case with most clinical entities in medicine, the cornerstone for evaluating a patient with neutropenia is a detailed history and physical exam. Physicians should ask about symptoms such as weight loss, fever or night sweats, recent viral infections, medications and rheumatologic complaints.

Other aspects of medical history should include an evaluation of ethnic background to determine the likelihood of constitutional neutropenia. A dietary history should be taken, even though most of the usual nutritional deficiencies (such as vitamin B12 or folate deficiency) cause pancytopenia rather than isolated neutropenia. In patients with a history of significant gastric surgery, copper deficiency is also a possibility.

An initial assessment of circulatory and respiratory function (with active resuscitation where necessary) should be followed by cautious examination for potential foci of infection. Particular attention should be directed to the oropharynx and periodontium, sites of catheters and recent procedures, lymphadenopathy in various parts of the body, as well as external auditory canals.

The pattern of recent or recurrent infections is significant in defining both the duration and clinical significance of existing neutropenia. Recurrent infections in a patient who previously enjoyed good health can help pinpoint when the neutropenia began and also give insight into whether it reflects a serious illness.

Laboratory assessment

Once neutropenia is suspected, further investigations should ensue. The first step is identifying whether neutropenia is isolated or there are associated signs of bone marrow failure, such as anemia and thrombocytopenia. Therefore, preliminary steps should include a complete blood count (CBC) with differential count and smear to assess neutrophil morphology.

The examination of bone marrow is often compulsory in order to exclude malignant pathology, to determine bone marrow cellularity and to assess myeloid maturation. Maturation arrest at the promyelocyte stage often occurs in severe congenital neutropenia, whereas hypercellularity with increased myeloid precursors and few maturations suggests a diagnosis of drug-induced neutropenia.

Relevant laboratory investigations in the context of progressive or persistent neutropenia over two weeks include Coombs test (direct antiglobulin test) for associated hemolytic anemia, immunoglobulins (IgA, IgG and IgM), antineutrophil antibodies, viral serologies, screening for autoimmune diseases, as well as DNA analysis for different mutations.

Although a specific organism is not found in half of the patients with febrile neutropenia, a presumptive diagnosis of infection is pivotal due to the risk of withholding antimicrobial therapy. Chest radiographs are not mandatory, but are suggested when there is clinical evidence of a respiratory infection.

In a non-urgent setting, it is reasonable to observe the patient for six weeks, obtaining CBC and differentials three times a week and correlating the neutrophil counts with the number of infections, fevers, and any changes in oral health (e.g. ulceration and gingivitis). If a patient has severe neutropenia, referral to a specialist hematologist is necessary.

Neutropenia and the Neutropenic diet

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Nov 10, 2022