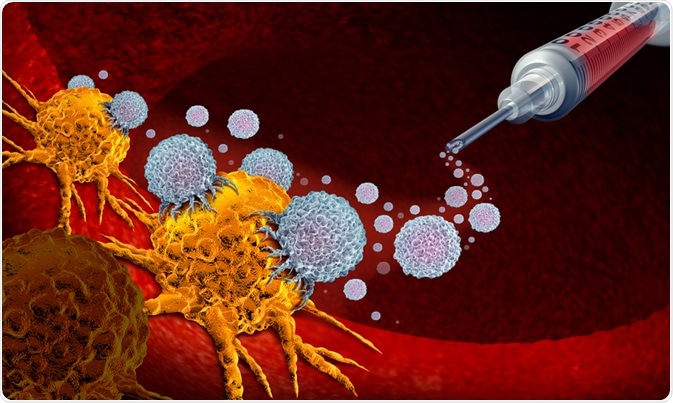

Immunotherapy is a treatment that is designed to harness the ability of the body’s immune system to combat infection or disease.

Image Credit: Lightspring / Shutterstock.com

How does immunotherapy work?

Immunotherapy might produce an immune response to disease or enhance the immune system’s resistance to active diseases such as cancer. Sometimes referred to as a biological therapy, immunotherapy often uses substances referred to as biological response modifiers (BRMs). The body usually only produces small amounts of these BRMS in response to infection or disease; however, in the laboratory, large amounts of these BRMs can be generated in order to provide therapy for cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and other illnesses.

Examples of immunotherapies include monoclonal antibodies, interferon, interleukin-2 (IL-2), and colony-stimulating factors CSF, GM-CSF, and G-CSF. Interferon is currently being used to treat hepatitis C and is also being tested, along with IL-2, as a treatment for advanced malignant melanoma. Immunotherapy is being investigated as a means of blocking the inflammation seen in conditions such as Crohn's disease and rheumatoid arthritis.

Depending on the type of treatment, various side effects can arise as a result of using immunotherapy. Side effects include flu-like symptoms, muscle aches, fever, appetite loss, weakness, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. A rash may develop and some people bruise or bleed easily. These side effects are generally short-term, but patients may need to stay in the hospital if they develop severe problems.

Cancer immunotherapy

In cancer immunotherapy, certain parts of the immune system are used to fight cancer in several ways. Some biological therapies are designed to boost the immune system generally, while others help train the immune response to specifically target cancer cells. Immunotherapy may be used alone or in combination with other therapies, depending on the type of cancer a patient has.

How does cancer immunotherapy work?

The immune system is able to keep track of all the substances that are usually present in the body. If the immune system detects a substance that it does not recognize or sees as “foreign,” it flags that substance for the attack via an immune response.

For example, germs and cancer cells contain certain substances that the immune system does not recognize as normally being present in the body. This raises an alarm that leads to a targeted immune response against germs or cancer cells.

However, there are clearly limits to the body’s ability to target cancer cells, as many people develop cancer despite having a healthy immune system. Sometimes the immune system fails to recognize cancer cells as foreign and these abnormal cells then proliferate in an uncontrolled manner to form a tumor. In other cases, the immune system does recognize cancer cells as foreign but the response it launches is not strong enough to eliminate cancer.

Experts have therefore developed ways to help the immune system recognize cancer cells and also enhance its response to ensure that the cells are destroyed. Some of the main types of cancer immunotherapies now being used are described below.

Monoclonal antibodies

One immune system response to foreign bodies is to produce large amounts of antibodies. These antibodies recognize and stick to certain proteins, also known as antigens, that are found on foreign bodies. Once bound to the antigens, antibodies recruit other immune system components to attack and destroy any cell that has the antigen.

Researchers can now generate antibodies that target one antigen in particular, such as one presented by cancer cells. These antibodies are called monoclonal antibodies and scientists can produce many copies of them in the laboratory once they have identified the correct antigen to target.

Over the last 20 years, more than a dozen monoclonal antibodies have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat certain types of cancer. Many additional monoclonal antibodies are currently being tested in clinical trials as scientists continue to discover different antigens associated with cancer.

Cancer vaccines

Cancer vaccines work in a similar same way as those given to prevent infections such as chickenpox or measles. Vaccines designed to prevent infection use dead or attenuated germs, such as bacteria or viruses, to initiate an immune response. Cancer vaccines do the same thing, but they instead trigger the immune system to attack cancer cells.

Cancer vaccines may be composed of cancer cells, cell components, or pure antigens. Immune cells may be taken from a patient and exposed to these substances in a laboratory to produce the vaccine, which is later infused into the body to enhance the immune response against cancer cells.

Vaccines may also be combined with other cells or substances, referred to as adjuvants, to create an even stronger immune response. These vaccines harness the immune system to attack cells that present one or more specific antigens. Since the immune system has specialized memory cells, the hope is that the vaccine will have lasting effects long after it is administered.

Sipuleucel-T

Known commercially as Provenge, sipuleucel-T is the only vaccine that has received FDA approval as a cancer therapy. The agent is used to treat advanced prostate cancer in cases where hormonal therapy is no longer helping.

The process involves removing immune cells from a patient’s blood and sending them to a laboratory where they are exposed to substances that turn them into specialized immune cells referred to as dendritic cells. In addition, the immune cells are also exposed to the protein prostatic acid phosphatase (PAP), which is intended to initiate an immune attack against prostate cancer cells.

These altered cells are then infused back into the patient. The cells are infused again on two more occasions, separated by two weeks, meaning the patient receives a total of three doses of the dendritic cells. The dendritic cells then help other immune cells to destroy the prostate cancer. This has been shown to improve patient survival by several months and the vaccine is currently being investigated to determine whether it can be used to treat men with less advanced forms of prostate cancer.

Many other vaccines have shown promising result in clinical trials but have not yet reached the stage of FDA approval.

Crohn's disease

There is currently no treatment that can cure Crohn's disease; however, advances in mucosal immunology have led to the discovery of a wide range of new targets for resolving the inflammation seen in this condition.

Research suggests that the intestinal inflammation starts because of an aberrant response by the innate immune system that is eventually driven by T cells. Current therapies are focused on inhibiting, altering, or suppressing T-cell differentiation. In the United Kingdom, the medications azathioprine or mercaptopurine are the most frequently used in the treatment of Crohn's disease.

In cases of severe Crohn;s disease that is not helped by these drugs, two biological therapies are available that may be used to treat the condition. These powerful immunosuppressants are called infliximab and adalimumab, both of which work by targeting a protein called tumor-necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). TNF- α is a cell signalling protein (cytokine) secreted by T-helper-1 cells that has been shown to play a critical role in the inflammatory process seen in Crohn's disease.

Infliximab is administered via intravenous infusion in the hospital. Comparatively, adalimumab can be administered via an injection, which the patient themselves or a family member may be able to learn to do themselves.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis can be treated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDS) to slow progression of the disease and prevent permanent damage in the joints and other tissues. Examples of these DMARDs include methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine and sulfasalazine.

However, in cases where methotrexate or other DMARDs fail to ease symptoms and inflammation, a biological therapy may be recommended to block certain parts of the immune system that contribute to inflammation in this condition. Biological treatments such as etanercept, infliximab or certolizumab are usually taken in combination with a DMARD. These immunotherapies are administered via injection and stop chemicals in the blood from activating an immune response that attacks the joints.

References

Further Reading

Last Updated: Aug 16, 2023