Humans are multicellular organisms, a complex system of billions of cells of around 200 different types. These cells must divide and copy themselves to carry out essential processes such as growth and tissue repair.

Image Credit: Yurchanka Siarhei/Shutterstock.com

Each day in the average human body, around two trillion cells go through mitosis, a process of cell division. Over a lifetime, around 10 quadrillion cell divisions take place in the human body, but not all of these divisions follow the pre-programmed rules of mitosis. It is these abnormal cell divisions that form the basis of cancer.

The cell cycle and cancer

The cells of the human body are governed by a set of pre-programmed processes, known as the cell cycle, which determines how cells progress and divide. Deviations from the cell cycle lie at the center cancer initiation and development.

A complex series of signaling pathways dictate how cells grow, copy their DNA, and divide. There are also processes involved in correcting for errors in divisions, such as triggering apoptosis, a programmed form of cell death, to remove mutated cells and prevent them from growing and dividing further. Essentially, these regulatory processes prevent disease by ensuring that cells divide and grow correctly.

When the cell cycle malfunctions and regulatory processes fail to correct these mistakes, the result is uncontrolled cell proliferation, the hallmark of cancer. As time passes, these cells diverge even further from normalcy, making them even more resistant to the regulatory processes that exist to eradicate errors maintain normal tissue functioning. At this point, the disease has been established.

Genetics, cell division, and tumor formation

Research conducted by the Cancer Genome Project has revealed that typically, cancer cells have accumulated at least 60 mutations. Scientists have worked on revealing which mutations, in particular, are related to specific types of cancer. As a result, it is now understood that some genes are mutated more than others in cancer cells.

Studies have revealed that mutations in some genes are more prevalent in certain kinds of cancer. Extensive investigation into these genes has uncovered the role of many of these genes in the maintenance of cell growth patterns, either directly or indirectly. Mutations to these genes, therefore, increase a person’s risk of developing cancer by allowing cells to proliferate, dividing in a pattern uncontrolled by normal regulatory processes.

Evidence has found that there are specific genes that are usually mutated in certain cancers, known as the mutational signature. Additionally, studies have also revealed several genes that are frequently mutated across cancer types, signaling their role in cell division, and maintaining the cell cycle. This knowledge has enabled scientists to develop and evolve new treatment strategies for cancer.

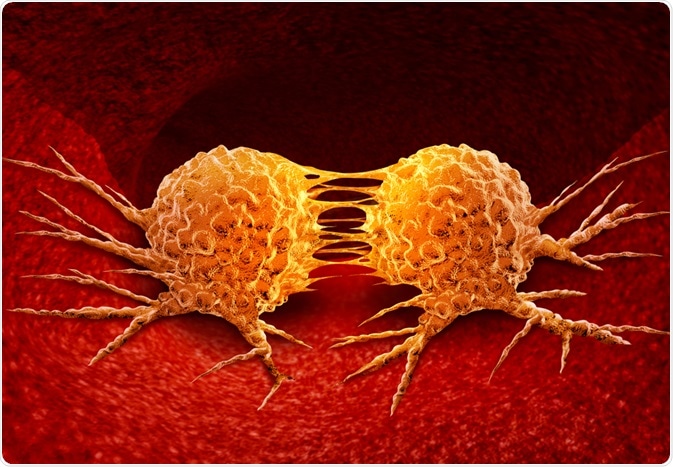

Cell division and metastasis

Once cells within a tissue begin to proliferate unhindered by processes such as apoptosis, the tumor it creates is often initially benign. While unchecked cell division leads to the formation of a tumor within a tissue, at first, the tumor is often contained by the tissue’s boundaries.

As time passes, and the cells within the tumor continue to divide and often secrete proteases then break down the extracellular matrix at the boundary of the tissue. At this point, cancer can break free from the confines of the original tissue and infiltrate the surrounding tissue. This is when the tumor becomes malignant.

Following this, cancer may metastasize as it enters into the body’s bloodstream or lymphatic system, allowing it to traverse and develop secondary tumors in new locations away from where the tumor first developed. The tumor continues to replicate through the process of cell division, creating more tumors throughout the body. Metastasis is considered to be one of the terminal stages of cancer, once diagnosed, a person with metastatic cancer faces poor survival rates and life expectancies.

Image Credit: Lightspring/Shutterstock.com

Treating cancer by targeting mitosis

Given that cell division is at the heart of cancer initiation and development, scientists have developed strategies to target cells that display increased mitotic activity while causing minimal damage to surrounding tissue.

For many years, anti-proliferative drugs have been the major class of drugs used to treat cancer. These drugs target the proliferative cycle of tumor cells at various points of the cell cycle. Types of anti-proliferative drugs include DNA-damaging agents, inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases, and anti-mitotic drugs.

This last class of drugs targets and disturb mitosis, preventing the progression of tumors by stifling the mitotic division that allows them to proliferate. Additionally, medicines have been developed to treat cancer by inhibiting the growth signals of the type of cell impacted by the tumor.

The future for cancer therapy

Cancer is characterized by cell proliferation, uncontrolled cell division allows tumors to establish themselves, and ultimately, it allows cancer to spread through the body and metastasize. Cancer research continues to explore effective ways to target cell division, as well as to understand how mutated genes lead to malfunctioning cell cycles.

In the future, more effective treatment options will likely be available that treat cancer by targeting cell division.

Sources:

- Brinkley, B., 2001. Managing the centrosome numbers game: from chaos to stability in cancer cell division. Trends in Cell Biology, 11(1), pp.18-21. www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0962892400018729

- Cell Division and Cancer. Nature. Available at: www.nature.com/scitable/topicpage/cell-division-and-cancer-14046590/

- Dominguez-Brauer, C., Thu, K., Mason, J., Blaser, H., Bray, M., and Mak, T., 2015. Targeting Mitosis in Cancer: Emerging Strategies. Molecular Cell, 60(4), pp.524-536. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1097276515008667

- Janssen, A., and Medema, R., 2011. Mitosis as an anti-cancer target. Oncogene, 30(25), pp.2799-2809. https://www.nature.com/articles/onc201130

- Preston-Martin, S., Pike, M., Ross, R., and Henderson, B., 1993. Epidemiologic evidence for the increased cell proliferation model of carcinogenesis. Environmental Health Perspectives, 101(suppl 5), pp.137-138. https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/pdf/10.1289/ehp.93101s5137

Last Updated: Sep 30, 2020