Antigenic shift is the molecular alteration of an antigen so that the human immune system can no longer recognize it. This means that individuals who have previously been infected can become re-infected and develop symptoms once more.

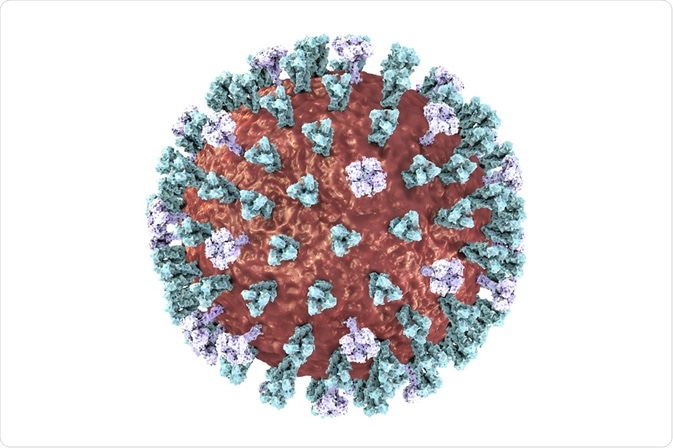

Credit: Kateryna Kon/Shutterstock.com

An antigen is a molecule which can be bound by receptors of the immune system, resulting in an immune response. When a foreign antigen is detected, the immune system works to eradicate the threat to the body. Once removed, highly specific receptors are produced which can detect the specific antigen faster and mount a highly specific attack upon re-exposure. This is known as the acquired immune response.

However, in order for the acquired immune response to function, the structure of antigens must remain the same as the produced receptors are very specific. Alterations in antigen structure, such as antigenic drift or antigenic shift, can mean that the antigen can no longer be detected by the acquired immune system and so individuals who have previously been infected are susceptible to reinfection by the same agent.

Whereas antigenic drift is the accumulation of small alterations in antigens over a long period of time, antigenic shift is a dramatic and sudden change. This process involves at least two different strains of a virus which combine and therefore produce a highly different antigen.

Influenza and antigenic shift

Whereas antigenic drift affects all strains of influenza, antigenic shift only affects influenza A, as it has a broad range of animal reservoirs. Antigenic shift occurs when an animal, particularly a pig, becomes infected with two or more different strains.

The genome of influenza is comprised for eight different parts, which can undergo reassortment. In a pig which is infected with both an avian and a human strain of influenza, reassortment can result in segments being swapped. This can result in the surface antigens containing a combination of the two different strains, meaning the acquired immune system can no longer detect them. Therefore, individuals who have previously been infected with a different strain of influenza can be reinfected.

When antigenic shift occurs, no one will have immunity to the new strain, which can result in a widespread epidemic or even a pandemic.

Pandemics resulting from antigenic shift

An example of a pandemic resulting from antigenic shift was the 1918-19 outbreak of Spanish Influenza. This strain was originally the H1N1 avian flu, however antigenic shift allowed the viral infection to jump from pigs to humans, resulting in a large pandemic which killed over 40 million people. As there was no previous resistance to the strain, no one was immune and so the virus spread rapidly across the world.

After this pandemic, the H1N1 strain would appear annually until 1957, when a new strain of influenza led to a new pandemic. This was identified as the H2N2 Asiatic flu. Again, no one had resistance to this new type of influenza and so it spread rapidly, killing nearly 2 million people.

Since this time, there have been numerous outbreaks of influenza due to antigenic shifts. Recently, the 2009 pandemic was identified to be due to a quadruple reassortment, which contained segments from two distinct swine flu strains, an avian flu strain and a human flu strain. This flu also spread rapidly and it is thought to have killed over 150,000 people.

The development of treatments against future influenza pandemics

Pandemics are still a major threat to the health of the world, as the appearance of a new antigenic shift would render all current flu vaccinations useless. Scientists and governments are working to improve methods of vaccine development and distribution in order to minimise casualties caused by future influenza epidemics. However, there is still much to be done into researching new vaccine technology as the current methods are complex and time consuming.

Antigenic Shift

Further Reading

Last Updated: Feb 26, 2019