In essence, immunochemotherapy refers to the treatment and management of disease by combining immunotherapy with chemotherapy.

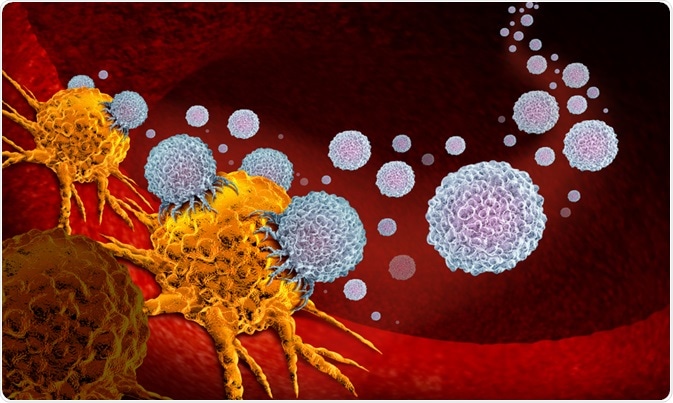

Image Credit: Lightspring / Shutterstock.com

Image Credit: Lightspring / Shutterstock.com

A vast body of research, collected over decades, has confirmed that chemotherapy (or radiotherapy) alone is not sufficient to destroy neoplastic lesions completely. The standard routine now implemented in most hospitals is that of combining chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy alongside immunotherapies.

The goal of this combination is to improve the treatment outcome for patients with cancer by allowing for a reduction in drug dosage required to combat the cancerous cells. Through supporting a reduced drug dosage, this combination therapy can decrease the severity of side effects that are classically associated with cancer treatment. Also, the combination of treatments addresses the possibility of chemo-resistance in malignant cells.

A multidisciplinary approach

The idea of immunochemotherapy comes from recognizing the value of combining different disciplinary approaches to gaining an understanding of cancer and developing more effective treatments.

Historically, different approaches to cancer treatment have mostly developed independently of each other. But recently, experts across these domains have opened up a dialogue, resulting in the combination of therapies, which has had the impact of developing immunochemotherapy as a new focus of clinical treatment.

Historically, immunologists have had a general lack of expertise in the genetics and pharmacology related to cancer, in the same way that cancer geneticists and pharmacologists have traditionally lacked a deep understanding of immune-based therapies.

Cancer immunotherapy and the genetic approach have both been around as separate areas of study for many years. But recently, the two approaches have been effectively combined. Immunotherapy as a treatment of cancer began as early as the 1800s when scientists first understood cancer as being linked to inflammation.

For the first time, researchers gained a key insight that the disease had its starting place within the body's cells. This revelation led to the conclusion that treatments that targeted the immune system could be useful in fighting cancer.

Research taking place during the 19th century found that the immune system has an influence on the development and growth of cancer, leading to the idea that treatments that could target the immune system could be effective in treating cancer.

Cancer genetics became an established school of thought from around 1980 when the discovery of oncogenes was made. Genetics took over the scene for a while, following studies in the late 70s that downplayed the role of the immune system.

Eventually, the study of genetics led to the development of a more advanced kind of chemotherapy, a targeted therapy that is able to locate and attack cancer's specific genes, proteins, or the tissue environment.

Finally, the last decade has seen the two disciplines join forces and work together to form a more comprehensive treatment for cancer, which combines cancer cell-centric therapy with host-centric therapy. The resultant immunochemotherapy is the combination of treating the immune system of the host along with additional treatments of chemotherapy, traditional radiotherapy, and surgery.

Immunochemotherapy and the treatment of cancer

Studies have provided strong evidence for the case that cancer cells must evolve the ability to escape the immune system, leading to the growth of rogue cells. Addressing this system of immune escape has become a key immunochemotherapy application within the field of cancer treatment.

The immune escape mechanism has been linked with metastasis invasion, angiogenesis, and metabolic activity. This theory evolved to gain a deeper understanding of how immune escape occurs, and that is through the acquisition of genetic mutations. This link between genetics and the immune system lends itself to the field of immunochemotherapy. It proves the case for addressing both the genetic level and the immune system to treat cancer.

The effectiveness of immunochemotherapy has been proven in treating various types of cancer, and evidence continues to mount. Currently, immunochemotherapy is the standard treatment offered for follicular lymphoma. Studies support that patients treated with a combination of chemotherapy and a monoclonal antibody or radioimmunotherapy show improved progression-free survival.

In addition, immunochemotherapy has become the new standard in treating aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in the elderly. Again, studies have shown that the combination of rituximab, a monoclonal antibody, with CHOP (the drugs cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin, and prednisone) chemotherapy results in survival benefits for elderly patients compared with those treated with CHOP alone.

Further studies have supported the idea that a mixture of group A Streptococcus pyogenes, which act as an immunotherapeutic agent, alongside induction chemotherapy may be beneficial to treatment outcomes of the suffering from the advanced stages of lung cancer.

Treatment of cervical cancer has also been seen to benefit from the immunochemotherapy approach. Recent studies have shown that the efficiency of chemotherapy in these cases is reduced by the escape of cancer cells from the immune system.

To address this, scientists have tested the effectiveness of a multifunctional nanohybrid system as immunochemotherapy against cervical cancer. Data has supported that this method increases the antitumor activity of cisplatin, helping to improve treatment outcomes.

The future for immunochemotherapy

The concept of immunochemotherapy is fairly new, only in the last decade have studies begun to show its use in the effective treatment of various cancers. As it is studied further, further therapeutic applications will certainly have the potential to be developed.

The benefits of combining immunotherapy with chemotherapy and other complementary treatments are that cancer cells can be more effectively and comprehensively targeted, in addition to in some cases being able to alleviate symptoms of traditional chemo and radiotherapies through decreasing the required dosage.

Sources:

Coiffier, B. (2003). Immunochemotherapy: The new standard in aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in the elderly. Seminars in Oncology, 30(1), pp.21-27. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12652461

Kimura, I., Ohnoshi, T., Yasuhara, S., Sugiyama, M., Urabe, Y., Fujii, M. and Machida, K. (1976). Immunochemotherapy in human lung cancer using the streptococcal agent OK-432. Cancer, 37(5), pp.2201-2203. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/1097-0142(197605)37:5%3C2201::AID-CNCR2820370507%3E3.0.CO%3B2-Q

Puła, B., Salomon-Perzyński, A., Prochorec-Sobieszek, M. and Jamroziak, K. (2019). Immunochemotherapy for Richter syndrome: current insights. ImmunoTargets and Therapy, Volume 8, pp.1-14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30788335

Shadman, M., Li, H., Rimsza, L., Leonard, J., Kaminski, M., Braziel, R., Spier, C., Gopal, A., Maloney, D., Cheson, B., Dakhil, S., LeBlanc, M., Smith, S., Fisher, R., Friedberg, J. and Press, O. (2018). Continued Excellent Outcomes in Previously Untreated Patients With Follicular Lymphoma After Treatment With CHOP Plus Rituximab or CHOP Plus 131I-Tositumomab: Long-Term Follow-Up of Phase III Randomized Study SWOG-S0016. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 36(7), pp.697-703. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29356608

Shah, G., Yahalom, J., Correa, D., Lai, R., Raizer, J., Schiff, D., LaRocca, R., Grant, B., DeAngelis, L. and Abrey, L. (2007). Combined Immunochemotherapy With Reduced Whole-Brain Radiotherapy for Newly Diagnosed Primary CNS Lymphoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25(30), pp.4730-4735. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17947720

Wang, N., Wang, Z., Xu, Z., Chen, X. and Zhu, G. (2018). A Cisplatin-Loaded Immunochemotherapeutic Nanohybrid Bearing Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Enhanced Cervical Cancer Therapy. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 57(13), pp.3426-3430. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29405579

Further Reading

Last Updated: Dec 4, 2019