Apr 21 2005

Giving children intermittent preventative treatment against malaria under the age of one can protect them from the disease in their second year of life, suggests a study in this week’s issue of The Lancet.

Giving children intermittent preventative treatment against malaria under the age of one can protect them from the disease in their second year of life, suggests a study in this week’s issue of The Lancet.

Infection with the parasite Plasmodium falciparum kills about a million African children every year. Using malaria drugs regularly can protect children from malaria episodes and death. However, stopping this treatment can be followed by increased risk of malaria, suggesting that it interferes with the development of antimalarial immunity.

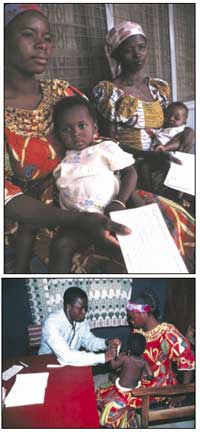

Following a trial involving 700 children in Tanzania, David Schellenberg (Ifakara Health Research and Development Centre, Kilombero, Tanzania and London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK) and colleagues, reported that the anti-malarial drug sulfadoxinepyrimethamine delivered just three times, at the time of routine vaccinations (2, 3 and 9 months of age), reduced the incidence of malaria by 59% in the first year of life when compared with a placebo. In their latest study they extended follow-up to two years to see if the risk of malaria increased during this period. They found the opposite: the rate of clinical malaria was 36% lower in recipients of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine than placebo recipients.

Dr Schellenberg states: “We have shown a continuing reduction in the risk of first or only episodes of clinical malaria in children aged 10 months to 2 years from intermittent preventative malarial treatment for infants. This finding increases the potential public-health benefits of such treatment.”

In an accompanying comment Imelda Bates (Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, UK) concludes: “Accumulating evidence about the effectiveness and safety of IPT [intermittent presumptive treatment] programmes is likely to increase pressure already placed on development agencies and governments by groups such as the Commission for Africa, to focus on strengthening health-care systems rather than individual components. World leaders will need to take account of this growing pressure during their Make Poverty History discussions, and to respond by translating it into genuine change to improve health-care through political commitment, resources, and action.”