Jun 28 2005

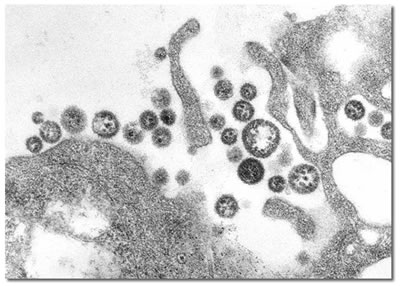

Among the family of viral hemorrhagic fevers (which includes those caused by the Ebola, Marburg, and Hanta viruses), Lassa fever is the biggest public health problem. A study in the June issue of PLoS Medicine by Thomas Geisbert and colleagues from the US Army Medical Research Institute for Infectious Diseases in Fort Detrick, Maryland and Heinz Feldmann, Steven Jones and colleagues from the Public Health Agency of Canada, now reports a promising new candidate for a vaccine against Lassa fever.

Lassa fever is endemic in certain areas of West Africa, where several hundred thousand people are estimated to be infected each year. The disease causes no symptoms or only mild symptoms in approximately 80% of infected patients, but the remaining 20% get very ill, and 1%–2% of those infected die. Death rates are particularly high for women in the third trimester of pregnancy, and for fetuses, about 95% of which die in the uterus of infected pregnant mothers. The most common complication of Lassa fever is deafness. Various degrees of deafness occur in approximately one-third of cases, and in many cases hearing loss is permanent.

Lassa fever is transmitted to humans from rodents that harbour the virus, and as the rodents are ubiquitous in the endemic area, the only realistic hope for control of the disease is a vaccine. Lassa vaccine initiatives have suffered from a lack of funding in the past, but bioterrorism and recent importation of the disease to the United States and Europe have brought new resources to Lassa virus science.

Geisbert and colleagues have developed new type of vaccine and tested it in macaque monkeys. They found that a single intramuscular vaccination protected all four vaccinated macaques against a lethal dose of a particular Lassa strain (i.e. a dose big enough to kill them), while two control monkeys that had received empty vector died after injection with the same dose of virus.

These are encouraging results, but future larger studies will need to assess the duration of protection and demonstrate the safety of the vaccine. Another crucial question is how quickly vaccinated individuals acquire protection, and thus whether the vaccine would be suitable for creating a ring of vaccination around an outbreak zone, the most likely early application of a promising candidate vaccine in humans.

All works published in PLoS Medicine are open access. Everything is immediately available without cost to anyone.