Mosquitoes can carry parasites and other organisms that cause deadly diseases such as malaria and dengue fever. So, protecting yourself against their bites is very important.

Repellents are often considered first in the line of defence against mosquitoes as they provide a protective barrier between you and the mosquito.

Why are some people more prone to being bitten by mosquitoes?

We have studied this for many years and have found that it is all to do with the way you smell. We all produce attractants but certain people who seem to never get bitten are producing a different body odour.

We have shown that their body odour contains greater concentrations of repellent chemicals – almost as if the body has a natural defence against mosquitoes!

Please can you give a brief introduction to mosquito repellents? How do they work?

The aim of a mosquito repellent is to prevent biting, but scientists are still trying to decipher exactly how they work!

Until now, we thought they may work in two ways:

-

By blocking olfactory (odour) receptors on the antennae (the mosquito’s nose) that are tuned into detecting human attractants, so that they can no longer smell human odour, or

-

By being actively detected by the receptors on the antennae and cause the insects to move away.

What is DEET and what types of mosquito was DEET thought to repel?

DEET is a synthetic repellent which was discovered around 60 years ago by the US Military. It is extremely effective and to this day is probably one of the most effective and most commonly used repellents.

DEET repels most species of mosquito and it can repel some other biting insects.

What was previously thought to be the reason why some mosquitoes were not repelled by DEET and what did your recent research reveal?

We showed in our previous research that there is a genetic component to being “insensitive” to DEET. In other words, a very small percentage of mosquitoes that are not repelled by DEET can pass on the genetic information to their offspring.

But in our recent study we showed that this “insensitivity” can actually occur in mosquitoes without involving any sort of breeding or genetics.

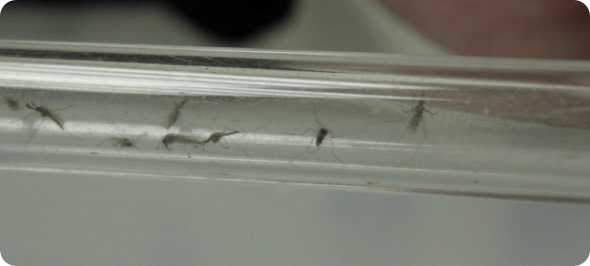

We took mosquitoes that are normally repelled by DEET, and exposed them to an arm covered in DEET. As expected, we saw the normal repellent action – the mosquitoes did not land on the arm.

However, when we took those same mosquitoes and then exposed them to DEET a second time, they were significantly less repelled and were more likely to bite.

We investigated this even further by attaching microelectrodes to the antennae of the mosquito and discovered that the receptors on the antennae are less sensitive to the chemical on the second exposure, which is likely to explain the difference in behaviour.

What type of mosquito was your research carried out on and do you think you would find similar results with other types?

Our research was done on Aedes aegypti, which transmits the pathogens that cause dengue fever and yellow fever. We do not know whether this phenomenon occurs in other species but we intend to investigate this.

Did your research help to elucidate the mechanism by which mosquito repellents work?

Yes, the study has given us an indication of how the repellent might work but we have more research to do to fully understand the mechanism.

Do you think the results of your study mean we should stop using DEET?

No. We should absolutely still use DEET as a repellent. It is still the most effective repellent on the market.

The next thing we have to look at is whether mosquitoes are able to overcome DEET under field conditions and whether this has an impact on the number of bites you receive.

Mosquitoes are remarkably good at evolving quickly to overcome our control measures. For example, we also see resistance to toxic chemicals. They always seem to be one step ahead!

The solution to this is to understand how the mosquitoes are able to do this so effectively, and this is what we have done in our study. The information will help us to work out ways around the problem before it gets out of control, or discover brand new, more effective repellents.

Do you have any plans for further research into other types of mosquito repellent?

Yes, we have several avenues of work where we are investigating different types of repellent and some new technologies which have a new mode of action.

Do you think mosquito repellents alone will ever be able to eradicate malaria and dengue fever?

No. It is unlikely that any one control method will eradicate these diseases. But repellents, could play a role in the future as part of an integrated approach which brings together many methods.

Your recent research showed that female mosquitoes infected with malaria parasites are significantly more attracted to human odour than uninfected mosquitoes. Did your study reveal the reasons behind this?

Our study revealed that infected mosquitoes find our body odour more attractive than uninfected mosquitoes.

We have recently been awarded a large 3 year grant to investigate the reasons behind this. We think that the parasite is manipulating the mosquito’s olfactory system, its sense of smell.

What further research is needed to investigate how malaria infection can cause mosquitoes to behave differently?

In our study we will be attaching microelectrodes to the antenna (nose) of the mosquito to work out which receptors are affected by the infection with malaria parasites. This will tell us how the parasite is manipulating mosquito behaviour.

What impact do you think this research will have on protection against malaria-infected mosquitoes?

We hope to discover new mixtures of odours which can be used to develop lures that can be used in traps to target those mosquitoes that are infected with malaria. This could provide a more accurate monitoring system for malaria.

Where can readers find more information?

They can access both papers from PLOS ONE:-

About Dr James Logan

Dr James Logan has more than 10 years of experience in the UK and overseas of controlling insects of medical and veterinary importance.

Dr James Logan has more than 10 years of experience in the UK and overseas of controlling insects of medical and veterinary importance.

He has a first class BSc honours degree in Zoology from the University of Aberdeen and an award-winning PhD investigating why some people are bitten more than others by mosquitoes and midges.

James joined the Department of Disease Control at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) and he runs his own research group investigating new ways to control insects that vector diseases.

James is also the CEO for the LSHTM Arthropod Control Product Test Centre (arctec) which is a world-leading independent test centre for consultancy, and the evaluation of arthropod pest control technologies, including consumer products. This involves coordinating large clinical trials on repellents, after-bite treatments and insecticides.

James is a Fellow of the Royal Entomological Society and is currently the Research Degree Coordinator for the Department of Disease Control, a member of the LSHTM Repository Steering Committee and the Public Engagement Committee.

In addition to his scientific duties, James is an avid science communicator and is a Science Ambassador for the Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics Network (STEMNET) which aims to inspire young people in science.

James makes regular appearances on television, radio and in print media as a scientific expert. He is also a science TV presenter, currently working on exciting science programmes with the BBC and Channel 4.