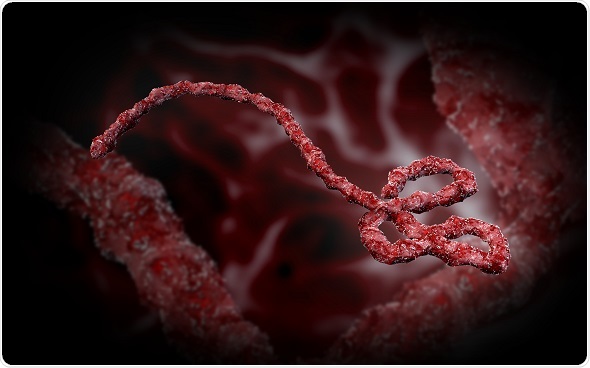

Ebola is one of the viral infections that makes up a group of infections referred to as viral hemorrhagic fevers. This is because it initially presents with a fever and for a proportion of the patients who become very sick with it, it can unfortunately end with hemorrhagic bleeding.

The virus multiplies in the body and lives within bodily fluids such as blood, urine, vomit and diarrhea, which is key to how it spreads.

However, humans cannot transmit the disease from another human unless that first human is infected and showing symptoms and signs of the disease. Then, it is transmitted through contact with infected bodily fluids.

Although this is how Ebola is transmitted in humans, we know that the West Africa outbreak started as a result of people eating contaminated bush meat.

Typically, that would be the bat, which is what we think is the natural reservoir of the disease. The virus itself lives in the blood and muscles of the bush meat and when it is consumed, it has the ability to replicate.

The virus doesn’t appear to make bats ill, but some evidence suggests it can have an impact on the animal by slowing it down. However, it certainly doesn’t seem to cause the same devastating effects in bush meat animals as it does in humans.

Shutterstock.com / Stock-Asso

Shutterstock.com / Stock-Asso

Why do you think there is currently a lot of confusion and misinformation around the Ebola virus?

I think certainly at the height of this outbreak, there was lots of misinformation about the Ebola virus within the community. This was very much predicated on old cultural and health beliefs and a concern that, in fact, it was the ‘whites’ who were effectively bringing the virus in.

Indeed, during the very beginning of the outbreak, the people who were treated by the doctors were those that were the most ill and therefore those who were most likely to die.

What happened then, is that people tried to avoid a healthcare situation and in doing so, they propagated it through the community because instead of being in isolation they remained around the family group and relied on usual cultural health remedies

External to the in-country situation, is the fact that in the Western world, there was initially a lot of concern amongst the public that Ebola could be caught very easily and could pretty much kill everybody. So, if just one individual was found with Ebola in the West, we would think we were going to have a very similar situation to that seen in Sierra Leone.

Not knowing the entity of the infection breeds fear, a fear that is often irrational because people do not understand or do not know the facts.

There have also been commentaries that, from my viewpoint, almost serve as conspiracy theories by implying that Ebola is now an air-borne infection and therefore more akin to flu in terms of risk and spread.

Of course, that then propagates fear, with people believing they can develop Ebola in the same way as they can flu, Influenza can be spread from people who are incubating the disease, but are well, if ebola could spread in this way individuals wouldn’t know if they had come into contact with someone who was infectious with ebola. So, people might believe, for instance, that if they’ve been in the same aircraft as somebody in whom the virus is incubating, that they will be at risk of developing the infection.

I think this whole confusion and misinformation has been based on certain facts that have been taken out of context.

This was an unprecedented outbreak, and our knowledge of Ebola since the mid-1970s has been more associated with rural, containable outbreaks that were limited to small communities, this outbreak took the International Medical Community a little bit by surprise.

Furthermore, some of the initial measures that were put in place such as initial treatment of cases was not that effective in terms of the outbreak because we had to get on top of the health behaviour aspects.

Together, the explosion of cases combined with the media coverage, meant that the outbreak became a part of normal everyday discussions amongst people who didn’t really understand the facts.

I think the size and location of the outbreak together with the fact that individual cases were seen in Spain and in the UK, continued to trigger an underlying fear.

How do International SOS try to counter this misinformation?

The really important thing about a new outbreak of any disease is to provide information about the same key themes.

International SOS have tried to do this in several ways. First we’ve made our website openly available to anybody, so it can be accessed even if you’re not an International SOS member.

The website provides information about what the disease is, what it is doing in these countries and what the risk of transmission is. For people who are really interested in the facts, this provides a source of information that is verified and accurate.

In addition, for people who are international SOS members there’s an Ebola app they can access on their smart phones while travelling, which will tell them the facts about Ebola.

We’ve also provided advice to travellers on an individual basis, as well as on a larger scale, by talking to companies about how they should frame information and advice to their travellers.

Within the countries themselves, we have provided lots of notice boards and leaflets that have been translated into many different dialects and languages, just to reaffirm the actual facts about the disease.

Although Ebola is a very scary disease, it is actually preventable because you can’t transmit it unless you’re with somebody who’s sick and those people who are sick are easy to identify.

We are using these approaches to try and empower people through knowledge and therefore debunk any of the myths surrounding the disease.

Shutterstock.com / Kristijan Puljek

Shutterstock.com / Kristijan Puljek

Is the current Ebola outbreak starting to decline?

I think that’s a really interesting question. Certainly, in January, it looked like there was a very promising decrease in cases across all three of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone.

What we’re seeing now is that, to some extent, that decline has stalled. So we’re not seeing a massive decline, but we are on the same trajectory in terms of cases decreasing.

This stall in decline is particularly relevant in Guinea and Sierra Leone, probably because there are small pockets of the community that are still very resistant to factual information and to seeking help from external medical providers.

We are therefore getting continued transmission in the community and amongst people that we haven’t actually initially identified as cases.

In Liberia, they have said there are no new cases at the moment so there’s a lot of optimism in that country.

I think we are just slightly cautious about whether that is true. Firstly, because, in terms of declaring a place Ebola-free, you need to look at two incubation periods, which means over 42 days.

However, if we look at the number of people that are being tested, significantly less people are showing potential symptoms, compared with in Sierra Leone and Guinea. Therefore I think it is probably safe to be optimistic.

Now, we are thinking that instead of fire fighting, we are on that trajectory of actively seeking out cases. A lot of the containment, which is the basis of disease control, is proving effective, so we are succeeding in beginning to stop that ongoing transmission.

On the other hand, in some stand-fast pockets in both Guinea and Sierra Leone, there is still some resistance to that and we should also remember that in April, we get the rainy season, which creates its own set of issues.

Even if there was just one case, I think the risk that it could ignite another small outbreak is still very real. So, we are optimistic, but it is tempered with realism.

What further action is needed to reduce transmission?

Still, the absolute key is case finding – finding people who’ve got the Ebola virus and then identifying all their close contacts. You can then start to look at the possibility of isolating or monitoring them in order to remove cases out of the community early on and prevent transmission.

Now, to be successful at this in Guinea and Sierra Leone, we need to carry out a lot more community engagement. We need to be getting the buy-in from key leaders in those communities, which is usually the elders. We need to convince them to buy into what the West is bringing and to work on the whole health belief system that these communities have.

Ensuring that we still provide enough treatment centers is also going to be important. It also needs to not just be about investing in Ebola containment, but actually looking at other developments side-by-side.

I think some of the reasons the situation has improved in Liberia is because there’s been engagement from the ground, root level, and up.

There’s been some very good work done in terms of engaging with those community elders and identifying who the key decision makers are, so they can be provided with information and the ability to identify cases, as well as personal protective equipment and the correct equipment for their local health facilities.

What travel advice is currently being given for Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone?

The International SOS are still suggesting people only undertake travel that is essential and that non-essential travel be deferred until the situation improves.

This is not simply because of the continued transmission of Ebola, but more because of the effect the Ebola outbreak has on things like a country’s infrastructure, particularly its medical facilities.

For example, Liberia was very limited prior to the outbreak and now they’ve lost a lot of healthcare workers and facilities. It’s going to take a little while for that to all be rebuilt.

In terms of infrastructure, there’s also the issue of access in and out of the affected countries. We still have airlines that are not flying into these areas of West Africa, which limits the opportunities for importing goods and for evacuating personnel. Although, overall the situation is being recovered, there’s still a risk to the travellers that go to these places.

What resources are available to people with questions about Ebola?

The International SOS website is very easy to navigate and sets out the geographical context of the outbreak in West Africa by providing a map of the affected areas.

It then gives an overview of the key issues in outbreak as we see them at the moment, as well as an overview about what has been happening in the main countries that have been affected – Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone.

The website also provides information about disease transmission, the symptoms and signs, and protective measures people can take, as well as the limitations on evacuating people who become ill. People can also access posters, leaflets, links to national websites and some webinars that talk through symptoms, signs and what we have been doing out there.

The website is free to access at the moment and anybody can log in to have a look. It’s open to all International SOS members, as well as non-members. In addition, all International SOS members can call into the assistance center if they have concerns about travelling to somewhere, travelling whilst out there or after travelling, when they return.

We still receive regular updates about the Ebola crisis and about the situation in terms of evacuation and the movement of aircraft in those places.

We still have a wealth of knowledge about what’s going on today, as we have people on the ground who feed back to us in real-time as a way of providing support.

What do you think the future holds with regards to the current Ebola crisis?

In terms of the three main countries affected, a key turning point will be identifying opportunities for businesses to come back into these countries in a safe and measured way, so that trade, which is so important to their gross national product, can start to increase.

That will help in the recovery of the country and I would say it’s probably critical that this starts to happen over the next six to nine months.

From a disease point of view, I would say we would now consider Ebola to be endemic in those regions, so, there will always be a risk of small, isolated outbreaks.

It is also important that we continue providing information about the disease to these local communities and ensure they still have the resources and resilience to deal with the disease, so that if a few cases do occur, the outbreak remains small and isolated.

In the long-term, I don’t think it’s about telling people to have an Ebola action plan, but there are key lessons that we have learned from our approach to Ebola that will help establish trigger and learning points for business continuity and emergency preparedness, planning, and response.

In terms of therapies, one experimental treatment that has been used early on in the treatment of another hemorrhagic fever called Lassa fever, has been shown to slow replication of that virus and aid patient recovery. Similar experiments are therefore being carried out for Ebola.

Only small scale experiments have so far been carried out in the West, so there is no clear evidence yet that these are beneficial, but there is also no clear evidence that they are not beneficial, so they are potentially promising.

I think it must be remembered that when drug companies are developing any kind of drug, they have to go through various phases. The first phase is to make sure that the drug itself is safe. The second phase involves finding out whether the drug actually has any positive impact on the disease it’s trying to fight.

So far, all of the experimental treatments for Ebola have been shown to be safe within a small group of people and certainly, if you’re treating people with Ebola and their risk of fatality is quite high anyway, then in the balance of risks from the safe drug in terms of whether it is effective is probably justified , because it is not going to be creating a risk to the patient’s life but may evoke survival.

Finally, the drug’s efficacy needs to be established and I think that over the next six to twelve months, there will be a lot more information about that and whether or not some of these drugs might actually prove useful, should there be another outbreak anywhere.

What are International SOS’ plans for the future?

Through working with Ebola, knowledge about the disease is now very broad amongst International SOS medical staff and we also have a good sense of the impact on security and in terms of operational responses.

We have learned these lessons and we’ll use this to perform a sanity check on any of our response programs in the future, to make sure that we’re capturing useful, generic information from the Ebola crisis.

When you respond to a crisis, it’s not only the actual incident or event itself that matters, but what it does to you as an organization. In terms of how we respond and our internal procedures, those have all been refined as we’ve gone through the crisis. We have built on our previous experiences and we can use that to improve response plans in the future.

As a company, International SOS is very much looking to incorporate more digital means into our health information and advice. We use a lot of telemedicine and telehealth for our remote support and it’s about how we can integrate that into our less remote support to improve members’ experience.

There’s also a big push to look at prevention and information because if we can prevent people becoming ill when they go on holiday, then we save them and their companies a lot of heartache, as well as increasing productivity for those companies.

Another big push for 2015 is to emphasize to companies the importance of prevention and planning at every level, from making sure the individual traveller has had their vaccinations and got the appropriate drugs, right through to thinking about what businesses can do in terms of global resilience and business continuity.

Where can readers find more information?

The International SOS website is a really good source of information and also provides links to additional information from other organizations. There, you can find links to information from WHO, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and the CDC in the United States.

https://www.internationalsos.com/

About Dr Katie Geary

Medical Director - Assistance

Northern Europe

International SOS

Dr. Katie Geary is a consultant physician in Public Health and communicable disease control who joined International SOS in 2013. She manages a team of doctors and nurses who with her deliver healthcare and medical assistance to client organisations and individual members globally. Dr. Geary and her team provide medical advice utilising telemedicine techniques for oil and gas installations predominantly in the North Sea, but also globally for certain clients.

Prior to joining International SOS, Dr. Geary worked as a Consultant in Communicable Disease Control for the Health Protection Agency. For the 2012 Olympics she was part of a small team of consultants working with the European Centre for Disease Control to survey and assess infectious disease outbreaks globally for their impact on London.

Prior to this she worked in the Royal Air Force as the Public Health consultant in the Surgeon General’s Department. Dr Geary has operational experience in pre-hospital emergency care after training initially in General Practice. She has worked as a specialised adviser for projects with ECDC.

Dr. Geary completed her undergraduate training in Manchester, was awarded membership with distinction from the Royal College of General Practitioners and is a Fellow of the Faculty of Public Health in the UK.

She has post graduate qualifications in medical toxicology from Cardiff University and is a Member of the Faculty of Travel Medicine of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow.