The study showed that about thirty percent to maybe half of the leading causes of death in the world are preventable. These are risk factors that you could manage and thus you could prevent a lot of premature deaths.

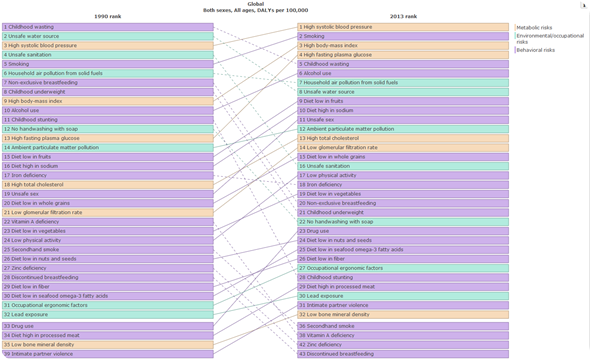

The main risk factors are high blood pressure, tobacco, obesity and diabetes. These have been changing dramatically since 1990 to now, which is a shift globally, seen by almost every country with different rate of change.

There has been a shift from risk factors of infectious diseases in nature such as unclean water, to factors that are more and more associated with non-communicable diseases, which has seen a rapid rise.

There are two other things that have happened during our study that we have adjusted for: the global population has dramatically increased between 1990 and 2003; and the demographic of the global population has aged. Even when these factors are accounted for the four main risk factors are still increasing globally and there is still a shift from infectious disease to chronic and non-communicable diseases seen all over the world.

What were the top 10 risk factors?

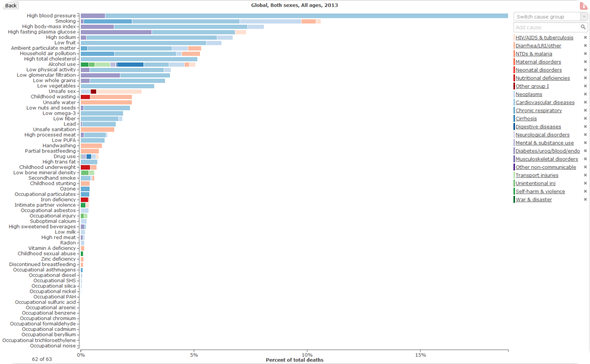

There is a lot of variation by country and region. The top rising factors in 2013 when it comes to risk were high blood pressure, smoking, high body mass index, high fasting plasma glucose, and a diet high in sodium and low in fruits.

Were the risk factors the same for both sexes?

No, there is a global variation by sex. For females, high blood pressure is the number one risk, high body mass index is number 2, and then diabetes is number 3. Whereas for men, high blood pressure is the number one risk, then smoking, and then high body mass index.

There is also a different variation depending on the age group. At a younger age, less than 5, in some cultures there is a preference to take care of the boy more than the girl. However, the girls tend to be more likely to stay at home with their family with less external risks and less infection because they're not running outside, drinking dirty water. Girls are more likely be taught to cook so they also tend to have better diet.

In general, young adult men are more likely to be smokers, are more likely to get into a car accident and be a victim of homicide. While at an older age, men continue to be smokers, are more likely to have high blood pressure and more likely to drink more alcohol.

Women are more likely to gain weight, which increases their BMI and increases the risk of high blood pressure and diabetes. Women often see other factors as their main risks, like breast cancer because of the recent well-deserved attention. Although right now heart diseases, in particular ischemic heart disease is the leading cause of mortality among women in almost all western countries and in most developing countries.

It should be noted that, while the attention on breast cancer should be maintained, women are taking care of themselves by doing a mammogram, following up and checking for breast cancer and other cancers and they're less likely to adhere or check their blood pressure, their cholesterol level or blood glucose level because they don't see it as a risk factor.

There is a difference in perception even in the medical field. As a medical doctor in the US when you have a patient that has the risk factors for cardiovascular disease of: being male, being above 50 and having high blood pressure or cholesterol, that bumps that patient into the vigorous treatment category and doctors will be more aggressive in giving medications for those risk factors.

Being a woman above 50 is not seen as a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases. That explains some of the changes and some of the variations you see by age and by sex.

Why do you think the increasing impact of high blood pressure has been more dramatic for men than women?

Men, tend to have blood pressure which is associated with a pathway based on behavior, their background, lack of physical activity and gaining weight. Men in their middle life are less likely to be physically active, and they're more likely to be worse at dealing with stress.

Women are better at multitasking and dealing with stress in general. They're more likely to talk about it and seek medical care through their friend or medical network. Men don’t have more stress than woman, but men don't handle the stress as well as women.

Thirdly and most importantly, men are less likely in many cultures to check for blood pressure because it is silent. If a man doesn't have any symptoms to take to a doctor he won’t, so usually it's diagnosed at a later stage.

Whereas woman in the childbearing age group, 15 to 50, are more likely to go to a doctor for other reasons. They're more likely to check their blood pressure giving them an early warning about blood pressure.

How do the risks for children differ to those of adults?

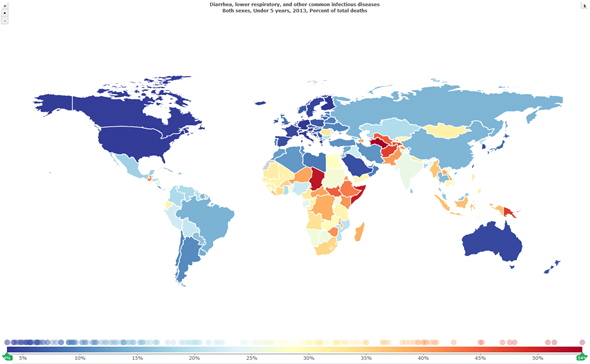

There’s more variation by country, their development state and the wealth of a country. In terms of causes of child mortality in developing countries it is mainly infectious diseases; newborn complications, lower respiratory infection, pneumonia etc.

Diarrhea is one of the top three killers in the poorer countries along with sepsis, through meningitis, typhoid fever and measles. Where you’ve got infectious disease in children, that's the leading cause of death.

In developed countries, the risk factors tend to vary differently because of the wealth of the country. Risks such as congenital heart diseases becomes more of a problem, neonatal complication will become more prominent, as well as others, but it's not so related to diarrhea, pneumonia, lack of nutrition or lack of sanitation.

Between, 5 and 18, there is a much larger global variability. The highest risks in many developing countries is road traffic injury and accidents. In many of the poor African countries, some of the infectious diseases and some AIDS become a prevalent risk of death. While, in places like South America we see in this age group it's homicide by guns.

How have the leading risk factors contributing to deaths changed over the past decade?

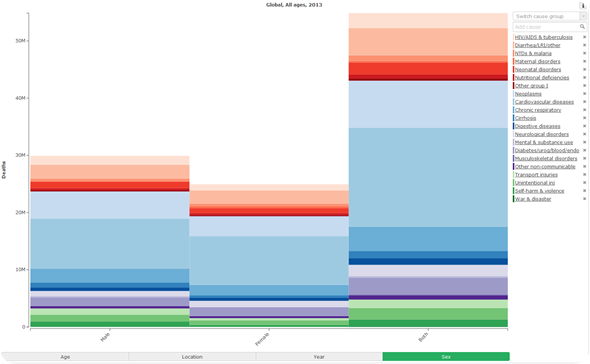

There is a tremendous success story globally of reduction in mortality, especially in the younger age group, less than 5 years old. The best reduction in mortality we have seen in this century.

Mortality declined throughout all age groups, so we're living longer right now. The shortest decline we saw in mortality is among the adolescence age. That's the challenge we see in that age group, a reduction in mortality but not as large as the others.

If you look at the things that are ailing us, such as mental health, back pain and neck pain, there wasn’t much of a global change. As a public health community, we have spent a lot of time and had a lot of success in addressing what's killing us but we haven't done so well in addressing what's ailing us, which is mental health, depression, anxiety.

The difference is that a gain in life has not been matched by a gain in healthy life. Some of us in many places of the world are living longer but with disability. That's the picture of health, living with chronic diseases.

Were you surprised by the latest findings?

Yes. First, the rapid shift that we are seeing in many places and in some countries that are still dealing with major burdens of infectious disease. In India, for example, there's still a lot of poverty, child mortality and maternal death but also a rapid rise in chronic diseases.

What's really surprising us, is that we were expecting a rise in chronic disease as a country gets more income and can afford more to keep themselves healthier for longer, but right now some countries are dealing with a double burden at a time when they haven't been able to handle the infectious disease burden.

In countries like the United States our major burden is chronic and non-communicable diseases, but we’ve had to some extent a great success story in handling infectious diseases.

The most surprising fact is how much variation there is between countries and within a region so you could go to a country in the Middle East or Europe. There are countries that are doing extremely well, like the gulf countries, while you see a country within that region, like Jordan or Egypt, they're not doing as well for the region, even factoring in for the instability there.

The other surprise that we are see is the variation we see within a country. In the US we spend more money on health than anybody else in the world as a percentage of our income. We have a lot of disparities in the United States between the states and even within the states by counties.

What we are realizing right now, with the burden of disease after completing reports in China, Mexico, Brazil, England and India, that there are a lot of variations that would have been missed and then would have been misleading for a country. Take India for example, if in India your number one burden is diarrhea, for example, but there's a huge variation and diarrhea itself is not a problem in one state and then you put all your efforts to deal with it in that state, where in reality it isn’t a high risk factor there, that can be a waste.

This is leading us and all our collaborators to move studies from a national level to a local level in many countries who have the data and have the formation to do it.

In what ways do you hope policymakers will use this information to guide prevention efforts?

This project is funded by a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation. The whole idea is for it to be a common good for everybody to have it. What we are hoping to do is to provide this data to a country, to the politicians, the decision makers and health officials.

They could come to know what the problem is, what their burden is and they will know what to do as a health intervention. That's very important, it focuses the debate on health, everybody agrees on the problems and can move to deal with it.

For the burden of disease, different groups have their own interests. A group working on anemia will produce a mortality rate for anemia, a group for cancer and so on. When you add all this information coming from everybody there are more deaths reported due to all the causes than the total envelope of mortality that could be in the world.

We mark diseases in exactly the same way, 1990 to 2013 across every country, this allows you to have a look at health and tell a country what their burden is. It also allows you to know what you are fighting and energise your population in order to act. So people could say hey, smoking is a problem here, what are you doing about it? We want to encourage that debate, that discussion.

Further, if the minister of health of a country asks for money to deal with a problem, they will need proof that that cause is a problem. We solve that problem. The minister will also need to prove the ROI, prove that the government or investing bodies have invested wisely. We keep doing the burden of disease reports annually, we have funding to do it for at least five years. That provides you with a way to monitor your success, what's working, what's not working.

Another way that these reports may guide prevention efforts is through contrasting programs in neighboring countries, as they will have different success rates. This promotes discussion among those countries and globally, asking why certain programmes worked better, that's very helpful.

Can you also outline how the study examined risk factors contributing to health loss? What were the main findings and how did they compare to the risk factors for death?

There's a variation between health loss, which is how much healthy life is lost living on disability or through premature mortality. In our data there is a huge variation by country and by region. Investigating all causes for the world the biggest contributors to health loss occur mainly in childhood through premature mortality from: wasting, unsafe water, breastfeeding, malnourishment and poor sanitation.

However, when studying health loss from illness or impairment, iron deficiency would become number one. Infants who are malnourished early on suffer for the rest of their lives from complications, disabilities and infection.

One of the largest single sources of health loss is unsafe water. At a global level most countries who have a large population, India, China, Pakistan, Nigeria, Ethiopia are still struggling with infectious diseases caused by unsafe water.

What do you think the future holds for risk factors to health?

There's good news and bad news coming up. We’ve reached a point when it comes to risks like tobacco that public health trends are coming down in some places, which is a great success story due to an aggressive policy against tobacco.

But it should be maintained and continued. Tobacco is a success story because of knowledge that tobacco is bad for you that spurred the policies put in place. Taxation, indoor policies and sales that have been successful.

The same could be done for other risk factors like diet and physical activity. If we could also rally the global decision maker on health, the UN organization to push against these risk factors, there is a potential for success and now people are more aware about this very important issue.

Unfortunately we also know that changing bad behaviors takes a long time, especially behaviors associated with non-communicable diseases, because they are part of our life. Many people are moving from rural to urban areas which increases risk factors. I know the risks from chronic diseases are not going to go away fast and I think it will take more time, a lot of policy and a lot of trial and error and setbacks.

Is the future gloomy? Are we going to keep getting fat and smoking? I don't think so. I would expect that we will live longer, we should spend more time on disability for us to live longer and healthier. Risk factors should be a priority for every country in the world. It shouldn't be an issue for the minister of health to deal with alone.

If the minister of health says eat well, eat fruits, vegetables and exercise to lose weight, to reduce diabetes and blood pressure. That is good but the minister of health is not in charge of designing a well-lit street where you can run safely enough without being hit by a car. They aren’t in charge of agricultural advising and how you bring fresh produce to a city like London, how to make it available and cheap so people have an alternative option. The minister of health is not in charge of fast food restaurants to force them to have a healthy option and this should be cheap.

We need to teach parents in schools, and kids in high school, this is where they develop their habits for their life. We need to try to get them to be physically active, but that's not the job of the minister of health, that's the minister of education. It's a bigger picture, that's why it takes more time to succeed and it has to be viewed as a society problem, not a health problem. A broader health problem.

Where can readers find more information?

For more information on Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), please visit: http://www.healthdata.org/

Readers can also access the data visualization interactive tool: http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/

About Dr Ali Mokdad

Ali Mokdad, PhD, is Director of Middle Eastern Initiatives and Professor of Global Health at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington. In this role, he is building IHME's presence in the Middle East through new research projects, dissemination and uptake of IHME's methods and results, and consultation with regional leaders in population health. IHME was founded in 2007 at the University of Washington to provide better evidence to improve health globally by guiding health policy and funding.

Dr. Mokdad leads IHME's Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Health Tracking project, which is creating an integrated health surveillance system for the Saudi Ministry of Health to monitor long-term and real-time burden of disease. He is also the principal investigator for the Salud Mesoamérica 2015 Initiative impact evaluation.

Prior to joining IHME, Dr. Mokdad worked at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), starting his career there in 1990. He served in numerous positions with the International Health Program; the Division of Nutrition and Physical Activity; the National Immunization Program; and the National Center for Chronic Diseases Prevention and Health Promotion, where he was Chief of the Behavioral Surveillance Branch.

Dr. Mokdad also managed and directed the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), the world’s largest standardized telephone survey, which enables the CDC, state health departments, and other health and education agencies to monitor risk behaviors related to the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the United States.

Dr. Mokdad has published more than 350 articles and numerous reports. He has received several awards, including the Global Health Achievement Award for his work in Banda Aceh after the tsunami, the Department of Health and Human Services Honor Award for his work on flu monitoring, and the Shepard Award for outstanding scientific contribution to public health for his work on BRFSS.

He received his BS in Biostatistics from the American University of Beirut and his PhD in Quantitative Epidemiology from Emory University.