Treating MRSA with certain first-line antibiotics can actually make MRSA skin infections worse, according to a study published in Cell Host & Microbe.

Ironically, patients can become sicker as a result of the treatment activating the body’s pathogen-defense system.

Study author George Liu (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, California, USA) says "Individuals infected with MRSA who receive a beta-lactam antibiotic – one of the most common types of antibiotics – could end up being sicker than if they received no treatment at all."

The finding potentially poses a problem for clinicians because beta-lactam antibiotics are frequently used as a first-line therapy in cases where the cause of infection is unknown. Since MRSA takes a couple of days to culture, early diagnosis can be difficult and in the meantime a beta-lactam antibiotic may have been prescribed as an empiric treatment.

"Our findings underscore the urgent need to improve awareness of MRSA and rapidly diagnose these infections to avoid prescribing antibiotics that could put patients' lives at risk."

Study author George Liu.

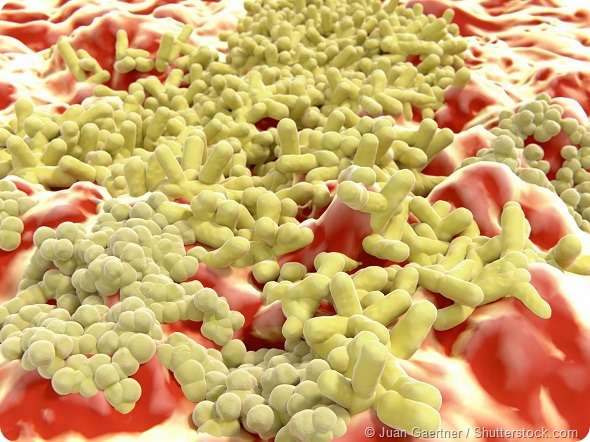

The bacteria Staphylococcus aureus (staph) is present on the skin or in the nose of about one third of healthy individuals, but about 1% have MRSA – staph that is resistant to methicillin and a number of other antibiotics. MRSA is the most common cause of skin and soft tissue infections in the US and is also more likely to cause serious illness or death than strains that are responsive to antibiotics.

The researchers say that the harmful effects of MRSA may be caused by the very gene that enables the bacteria to become resistant to antibiotics. Beta-lactam antibiotics destroy bacteria by inactivating the enzymes required for cell wall synthesis. However, MRSA avoids the effects of the drug by stimulating a gene called mecA, which provides an alternative pathway for cell wall synthesis. This enables the MRSA superbug to continue making its cell wall, which has a different structure to normal staph.

In the current study, Liu and colleagues looked at whether this structural change could trigger an immune response that worsens MRSA infections in mice.

They found that exposing MRSA to beta-lactam antibiotics activated mecA, which weakened chemical bonds in the cell wall, making it more vulnerable to degradation by immune cells. The degraded cell wall then released fragments that the immune system did not recognize, triggering a powerful inflammatory response that made the infections worse.

"We now have evidence that the very factor that defines certain S. aureus as MRSA is a factor that can also make MRSA more pathogenic,"

"However, this pathogenic factor is not unleashed unless MRSA is exposed to beta-lactam antibiotics. Therefore, a poor choice of antibiotic can make MRSA infection worse compared to no treatment."

Lead author Sabrina Müller.

Co-author David Underhill says that the obvious next step is to test whether the same response occurs in humans: “If human data suggest that beta-lactam antibiotics given alone could make MRSA infection worse, then we may need to rethink whether beta lactams should be our first choice of empiric antibiotic before the source of the infection is known, especially in case of severe infections."