Over the past decade, a lot of evidence has been gathered, which shows that one of the most important external triggers for this inflammation is the S. aureus bacterium. We know that it's S. aureus itself that ignites the inflammation and that it's independent of the antibiotic resistance mechanism.

MRSA is the “methicillin-resistant S. aureus”, indicating its extended resistance profile against multiple antibiotics normally used. Like the antibiotic susceptible S. aureus types, MRSA also can ignite this inflammation in eczema.

It's not the antibiotic resistance or MRSA itself that is more likely to cause this inflammation, but you can imagine that when you are colonized with a multi-resistant type of S. aureus (MRSA), treatment is more difficult, especially when secondary infections occur.

An Australian research group has shown that in the last 15 years, the presence of MRSA on the skin in children with eczema has increased from 0% to a three-year average of 10%, between 1999 and 2014.

That is because S. aureus is involved in eczema and when you live in a country where a lot of S. aureus is the multi-resistant MRSA type, then of course more people won’t have the susceptible variant of S. aureus, but the multi-resistant variant on their skin.

In the Netherlands, where we have low prevalence of MRSA, we do not see a lot of MRSA on eczema patients, but for example, in Australia, we see more than 10% of eczema patients with MRSA.

What did the recent systematic review from Erasmus University Medical Center involve?

It is the first time that all the academic scientific evidence that has been gathered over the last decade has been systematically reviewed and put into context. Ninety-five studies were included in the review.

All of them were checked for completeness of the description, the right patient selection and so forth, to make sure all the methodology in these studies was done correctly.

Then, you have a lot of studies that you can review, the conclusions of which can be put into one review. All this evidence pointed towards the involvement of S. aureus in eczema.

Prof. Suzanne Pasmans and Dr. Joan Totté described that eczema patients, for example, are 20 times more likely to have S. aureus on their skin lesion, than healthy controls. This is about 70-80% of all patients with eczema that are colonized with S. aureus.

Also, the review has shown that the disease severity of eczema in fact correlates with S. aureus colonization, so the more severe the eczema, the more likely that S. aureus is present. It is the first time that all that evidence has been put into context.

How do the results of this study compare to previous findings?

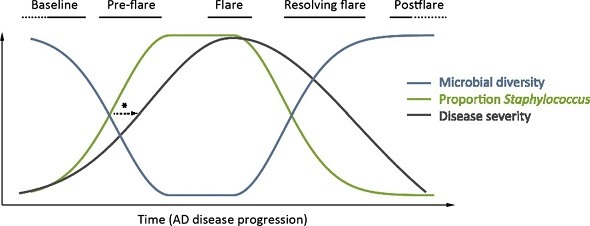

The study itself shows the gathered evidence of the involvement of S. aureus colonization in eczema and it fits nicely with other studies. For example, there was one study (Kong et al., Genome Research, 2012) that showed that a flare of eczema symptoms actually is preceded by a rise of S. aureus numbers on the skin. You have more S. aureus and then you get the flare.

At the same time, the biodiversity of the rest of the skin bacteria, the so called microbiome, is diminished. Right before a flare, you see an up-rise of S. aureus and you see a decrease in the others, including the beneficial skin bacteria. Then, you have the symptoms and the flare. This bacterial skin imbalance is restored after the flare has resided.

From: Kong, H. H., et al. (2012). "Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis." Genome Res 22(5): 850-859.

Available under a Creative Commons License (Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License), as described at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/

There was a very powerful study from the beginning of 2015 (Kobayashi, Immunity 2015) where the researchers had a mouse model of eczema. These mice have a genetic skin barrier dysfunction that resembles a known genetic factor in a subgroup of eczema patients.

These mice develop eczema symptoms as soon as they are colonized with S. aureus. There are some really interesting pictures of the skin of these mice, where you see that the skin cells do not adhere to each other.

There are some crests and openings in the skin between these cells and you see these grape-like bacteria feeding in there and that is S. aureus.

As soon as these mice become colonized with S. aureus, they develop the inflammatory skin symptoms resembling eczema. When the researchers treated these mice with antibiotics, they saw that S. aureus colonization decreased and subsequently, the symptoms of eczema decreased. This is a very powerful study. I think it shows that it is S. aureus that triggers this eczema-like inflammation.

Is there any evidence that this is a causal correlation, or is further research needed to rule this in or out?

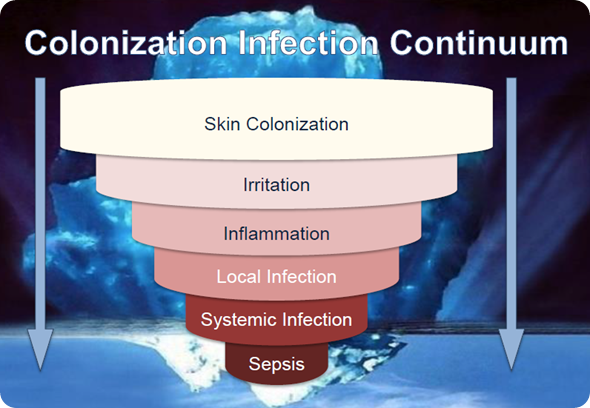

At this time, we're not sure; it's a hypothesis. We know from other studies that S. aureus produces a lot of toxins. With these toxins, S. aureus can act directly on the skin cells, immune cells and nerve cells.

These toxins are able to produce inflammation, pain and itchiness. All the evidence points towards the role of S. aureus as a trigger.

We have this hypothesis of skin barrier dysfunction making the skin prone to triggers like S. aureus, followed by an overshoot of inflammation, of the immune system.

However, if you look at how we treat eczema right now, we try to intervene at the skin barrier level by using Vaseline-like emollients and we use corticosteroids to decrease, dampen, and inhibit the immune system. We do not intervene at the level of the trigger of eczema itself; we do not intervene at the level of S. aureus.

Sometimes we do treat severely infected eczema with antibiotics, but why don't we intervene at that point as a regular eczema therapy? That's because antibiotics, the usual treatment for bacteria, are not suitable for a long-term suppression therapy because you see resistance and side effects, which is why we don't do this.

What impact do you think this review will have?

I think it will draw focus to S. aureus as a central trigger in eczema, so it will inspire more research to focus on intervention at the trigger level, instead of intervention at the later immune level.

If you eliminate the trigger, you don't need to have corticosteroids to dampen the immune system response.

What should prospective studies focus on?

As a doctor, I say patient benefit. We now know S. aureus is involved in eczema and we have a hypothesis on how S. aureus does this. The next question, of course, is can we reduce the number of S. aureus on the skin of eczema patients and will this lead to a patient benefit in terms of less inflammation, itchiness and pain? Also, will this approach have less side effects than other treatments?

What other treatments do you have for eczema? Well, it's the corticosteroids that inhibit the immune system. There are some risks with that. It could be that intervening at the S. aureus level would prevent the use of corticosteroids. Maybe you need less corticosteroids when you intervene at the trigger level.

About Dr Bjorn Herpers

Bjorn Lars Herpers graduated summa cum laude at Gymnasium Rolduc in Kerkrade, and studied medical biology, and later medicine, at the University of Utrecht. He graduated cum laude in medical biology in 1999 and obtained his medical degree in 2001.

After one year of residency in internal medicine at Gooi-Noord Hospital under supervision of prof.dr. D.W. Erkelens and dr. P. Niermeier, he switched to a residency in medical microbiology at the University Medical Center Utrecht and the St. Antonius Hospital Nieuwegein under supervision of Prof.Dr. J. Verhoef and Dr. B.M. de Jongh.

During his residency, he started to work on his thesis on genetic polymorphisms in MBL and L-ficolin, two complement-activating pattern recognition receptors. In 2009 he became a medical microbiologist and joined the staff at the Regional Public Health Laboratory Kennemerland in Haarlem. Dr Herpers acts as the Chief Medical Advisor to Micreos, a Dutch biotechnology company.