Sep 27 2016

Scientists from the Trypanosome Cell Biology Unit (Institut Pasteur/Inserm), working in collaboration with scientists from the University of Glasgow, have demonstrated the presence of a large quantity of trypanosomes – the parasites responsible for sleeping sickness – in the skin of individuals with no symptoms. This discovery should refocus the screening strategy for this disease, which was previously based on the detection of parasites in the bloodstream, and raises the possibility of eliminating the disease in West Africa. The scientists' results were published in e-Life on September 22, 2016.

Sleeping sickness affects between 4,000 and 8,000 people in Sub-Saharan Africa each year. The disease can be fatal if the parasites reach the central nervous system. "In recent centuries, sleeping sickness has almost been eradicated in West Africa on two occasions," explained Brice Rotureau, head of the Trypanosome Transmission Group in the Trypanosome Cell Biology Unit (Institut Pasteur/Inserm). "But each time the disease has reappeared, with many infected individuals seemingly slipping through the net during screening campaigns and continuing to transmit the parasite Trypanosoma brucei gambiense to its insect vector, the tsetse fly." It is thought that in at least 30% of cases, the serological screening test is positive, despite no living parasites being detected in the bloodstream. But if the parasites are not in the blood, where are they hiding? Here is the question that scientists from the Institut Pasteur, the University of Glasgow, the University of Kinshasa and the French Research Institute for Development (IRD) set out to investigate.

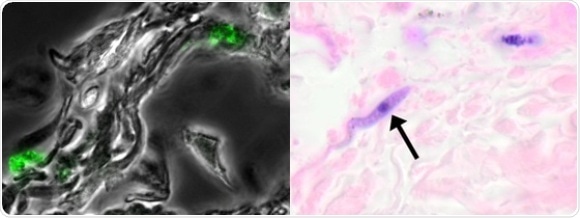

In this study, scientists from the Institut Pasteur decided to monitor the evolution and distribution of Trypanosoma brucei parasites in real time in mouse models. Trypanosomes that had been modified to emit both fluorescence and bioluminescence were transmitted to these mice via tsetse flies, their natural vectors. "We saw a huge number of parasites in the skin, a much larger quantity than in the bloodstream," described Brice Rotureau. "And at tissue level, we observed trypanosomes at the base of the dermis moving in the inter-cellular matrix, outside the vascular system. The parasites were distributed very evenly, as if they were trying to optimize their chances of being taken up by a tsetse fly so that they could be transmitted to a new host."

The scientists' research enabled them to prove that trypanosomes were hiding in the skin. But in order to provide conclusive evidence that the trypanosomes could be absorbed by flies when they feed on mice, they then exposed infected mice to naive tsetse flies. These mice had parasites in their skin but not in their bloodstream. The scientists' experiments revealed that when the flies fed on areas of the skin with no parasites, they were not infected. But the flies that fed on parts of the skin with a high density of parasites were infected. In other words, parasites in the skin can be transmitted to tsetse flies and can therefore result in new cases of sleeping sickness.

The study also demonstrated the presence of trypanosomes in the skin of African patients, including individuals who had received a negative diagnosis for the disease. These patients were actually healthy carriers who served as reservoirs for the parasite Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and who should have been treated. All these findings offer new hope for the treatment of sleeping sickness.

The scientists are now working on rapid and non-invasive screening procedures which would reveal any trypanosomes hidden in the skin and identify healthy carriers that have not been identified by previous screening tests. "Now that we know where to look, we can seriously think about eradicating sleeping sickness in West Africa in the relatively near future – especially since the epidemiological situation, with cases at a record low, is ripe for action," explained Brice Rotureau. "We hope that our work will provide a valuable tool that enables WHO to launch an eradication campaign on all fronts, involving screening, treatment of patients and healthy carriers, and vector control measures."

Source: http://www.pasteur.fr/