About eight years ago the WHO put out a call saying that we needed data that better represented real world patients. Our ambition was to create evidence earlier in the life cycle of medicine that better represented the population that would ultimately get the medicine.

For traditional, double-blind, randomized controlled trials, which are efficacy trials and absolutely essential, we have very selective groups of people that probably represent less than 15% of the population that will ultimately get the medicine in practice. Our vision was to create a study where we could get real patients behaving in ordinary ways and get the study done as early as we could in order to give data about effectiveness and safety in that population and to give payers, guideline writers, doctors and patients information that will better inform them about the risks and benefits of a medicine in everyday clinical practice.

We did this when this medicine was pre-licensed. A real world study with a pre-license medicine had never been done before. We then thought if we were going to try to do that, the thing we would need was an electronic health record that could document information from primary and secondary care in real time, so that we could almost create a real-life laboratory, a big brother environment, where patients could consent and be brought into a study, but then lead their lives normally.

The ambition was that all of the monitoring would be done through an electronic health record. We started to look around the world at places that had that capability and when we started this study, Salford was pretty much the only place in the world that could do that because it has had a long standing pre-existing integrated health record that started off with diabetes, but had evolved into almost everything. It has a large paperless hospital, so they had an integrated record.

There was a group called North West EHealth which is expert at pulling information out of that. That's really why we went to Salford.

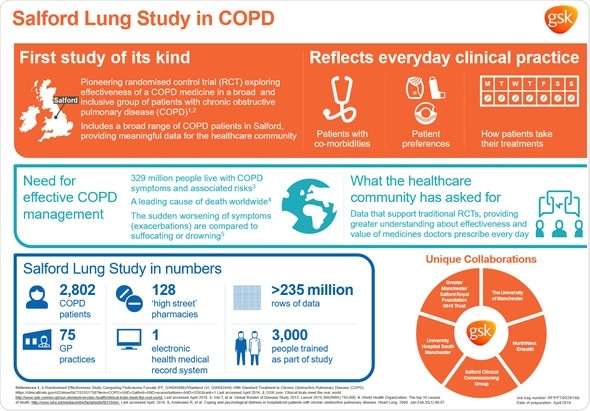

In terms of the COPD study design, firstly, it’s a big study, including 2,800 patients. We needed that to get the power to look at a meaningful endpoint, which we're using as exacerbations.

Secondly, the study population is very broad. Essentially, you have to be aged over 40; have a GP diagnosis of COPD; be on a maintenance treatment for COPD; be able to give consent and be expected to be alive in a year. There were very few exclusion criteria.

We were trying to capture as many of the normal patients as we could. Then, after they've been seen and have consented, we assess their lung function in detail, but we keep everybody in the study. That is very different to most studies.

Patients who are in this study are randomized to either the test drug or to usual care and usual care is what the doctors normally do, so that's a mixed comparison group. Then, those patients essentially just exist as normal for a year and then are seen and assessed again. However, the miraculous thing about this study is that the patients get their medicine in absolutely the normal way. Every single community pharmacy in the city and surrounding areas was recruited. Patients get their prescriptions from their doctors in the normal way and they collect them from the local pharmacist in the normal way, which is totally different to a normal trial.

During that year, they're monitored in real time through the electronic health record for everything that happens to them. The electronic system can trigger alerts if there are adverse events or if things of interest to us such as exacerbations occur. We were looking for steroid prescriptions, antibiotic prescriptions or hospital admissions in association with respiratory events as the surrogate for exacerbations.

Once the patient is randomized, they essentially just go ahead as normal; there's no protocol that drives care in either arm. The doctor optimizes treatment as they want. That's basically the design of the study, which is very different to what we'd normally do.

I think at the heart of this is the difference between efficacy and effectiveness research. They are complimentary and both are essential. What we're really good at in the industry is doing double-blind, randomized controlled trials that are very strictly controlled and then asking whether the medicine has the potential to work. What you're doing in an effectiveness trial is looking at a mixed population. It's not pure and there's lots of noise, so the question you're asking is what the medicine can really do in the population that ultimately receives it. You can think of efficacy as defining the potential of the medicine and effectiveness as defining what it really does.

It does pose challenges because traditional medical training is all about internal validity and the scientific robustness of the experiment, whereas effectiveness is all about external validity. The question of whether the medicine will work in a patient a physician sees in their clinic is a different question to whether the medicine works for a defined patient in a trial. You have to think about it differently and it challenges people's conventional thinking. The importance of assessing internal validity of studies has really been drummed into me because that's what I do and, yes, there are challenges there.

Why is it important to take into account the everyday lives of patients and the way they use their medicines?

I think all of us do the following, although I'll speak for myself. When I'm prescribed a medicine, I don't take it exactly as I should. I do normal things that people do such as take a break for a little bit, maybe not finish the course, or see if it works once a day instead of twice a day. Patients normally do that. That's a normal human condition.

What we do in efficacy trials is we really try to control everything, so we drive adherence. We make sure patients are incredibly well monitored; we're constantly seeing and checking them. The real world isn't like that.

We all do normal things. Many people smoke, drink, have social habits and other diseases and medications that would exclude them from normal trials. It is important to get information that will help assess the effectiveness of a medicine in the population that will ultimately receive it, where people are doing things that people normally do because that's what patients are like. I think that's at the heart of it really.

How many patients with COPD have other conditions and why are they often excluded from traditional trials?

COPD affects people who are older. They often have smoking histories and the disease itself is an inflammatory condition, so it's associated with an excess of diseases that are not just caused by the smoking exposure.

There's a very high instance of cardiovascular risk and diabetes. In Salford, about three-quarters of patients had comorbidities. In normal trials, you exclude those individuals because you're trying to very accurately assess the safety and efficacy of a medicine in a tightly as controlled way as possible. You want to reduce the noise that's created by other conditions, so, for good scientific reasons, those people are often excluded, whereas in this trial, obviously, we welcome everyone in, regardless of what other conditions they have.

What impact do you think the Salford Lung Study will have on future trials for COPD?

I think it's a starting point. I don't think this is going to trigger a revolution. I think people have wanted these data sets, but have never had them. Now, we've got a data set, a quality publication and a result. People can now look at those and try to understand what it means for them.

Clearly, this is absolutely new and not a part of current evidence hierarchies. Regulators, payers and guideline writers are all going to have to weigh up what they think this data means and include it. Then, I think perhaps we will see adaptations of this type of design. I think there are many different ways we could do these studies. I think it's going to be an evolution, not a revolution.

How in turn will this affect COPD patients?

I think this is about much more than just the medicine we were testing. Obviously, we know that the drug did have an effect on exacerbation rates in Salford, but, within this data set now, we've got about 240 million rows of data, which are about people's everyday care. We have information about how people behaved, how their doctors treated them and a wealth of information to help us understand how we might better develop treatment approaches in COPD, including how people respond when they've got comorbidities or when they're current smokers.

There are a number of things I think this study will allow us and I think there will be many publications, actually, about these type of things and what really happens to patients when you treat them in a clinic rather than in a study. I think there will be lots of information coming out. I do believe there will be benefits for patients, not just in terms of drug treatments, but in terms of understanding how COPD patients are affected by their disease and how they behave with healthcare professionals.

Do you think an inclusive approach to research would also be beneficial for other conditions?

Yes, I do. I think it's particularly useful for conditions where there are comorbidities or where there are aspects about the disease such as monitoring, which may be different in clinical trials to in the real world.

Just off the top of my head, for example, diabetes might be one because, obviously, diabetics have to monitor their blood sugar and adjust their treatment. In clinical trials, that’s done under supervision. We all know, because we've probably got diabetic friends or family members, that diabetics don't really do that and there's some middle ground. I think what’s worth looking at is the monitoring of common conditions that exist with comorbidities, where behaviors very strongly interact with the treatment of the condition. It's probably less important for acute, short-lived conditions, although I still think it could be of some value.

What do you think the future holds for COPD research?

I think COPD has really changed in my lifetime. If I just look back over the last 10 years, I can see it's a very fast moving field. At one time, the sense I got when I was a GP was that it was a pretty hopeless and chronic condition that was caused by smoking. There was not a lot of interest and the guidelines weren't terribly helpful.

I think the real future is in defining the phenotypes in COPD and understanding which patients respond to which treatment approaches and what the treatment pathways should be. We've got a variety of treatments.

Obviously, there will be new treatments emerging and, I'm sure, coming through different companies’ pipelines, but fundamentally, I believe it is about saying COPD isn't one condition. It's a group of different conditions and understanding those in terms of their science, their pathology, and the behaviors that go with them, will define groups that will respond better to some treatments than others. I think that's where the action will really be in the future.

How was the Salford Lung Study made possible?

The Salford Lung Study has been a colossal endeavor and whenever it's possible for me to thank people for that, I’d like to. When you think that every single GP in the town, every single community pharmacist, the secondary care hospitals, the academic groups and the electronic health record people were all involved, it is quite incredible. We built that, kept it working, and managed to complete a study, which has taken about eight years so far.

The collaboration is quite exceptional. One thing that I think we never realized was that it’s about much more than a database. It's actually far more about the collaboration and recruiting patients from primary care. To recruit this number of patients in one city is amazing. We owe a great deal of thanks to our collaborators and the patients who volunteered. That's the key thing. GSK were already a part of this. It's been an incredible thing to be involved in.

Where can readers find more information?

www.gsk.com

About Dr David Leather

FRCGP, FFPM: Medical Vice President GSK Respiratory Franchise London

Dave Leather is a Global Medical Affairs Leader in the Respiratory Franchise at GSK, based at GSK House in London in the UK. He leads the Global Medical Expert team: a team of world renowned Respiratory experts who work for GSK providing internal scientific and clinical expertise to support promoted medicines and those in development. For the last 3 years he led a team responsible for developing phase lll and phase lV trials for respiratory medicines. He also has a leadership role in “real world pragmatic trials” and is the Franchise leader of the internationally recognised Salford Lung Study.

Dave Leather is a Global Medical Affairs Leader in the Respiratory Franchise at GSK, based at GSK House in London in the UK. He leads the Global Medical Expert team: a team of world renowned Respiratory experts who work for GSK providing internal scientific and clinical expertise to support promoted medicines and those in development. For the last 3 years he led a team responsible for developing phase lll and phase lV trials for respiratory medicines. He also has a leadership role in “real world pragmatic trials” and is the Franchise leader of the internationally recognised Salford Lung Study.

He joined GSK in 2000 and has held a variety of posts within the company. Originally a primary care physician in Bolton with an interest in respiratory disease, Dave managed asthma and COPD clinics in a primary care setting and held a post as a clinical assistant in Respiratory Medicine at University Hospital Aintree in Liverpool. He was a GP Course Organiser, a member of the Council of the Royal College of GPs (RCGP), and worked as a media doctor for the BBC and commercial radio.