A new study highlights the urgent need for global equity in vaginal microbiome research, challenging outdated perspectives and pushing for better diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for female health worldwide.

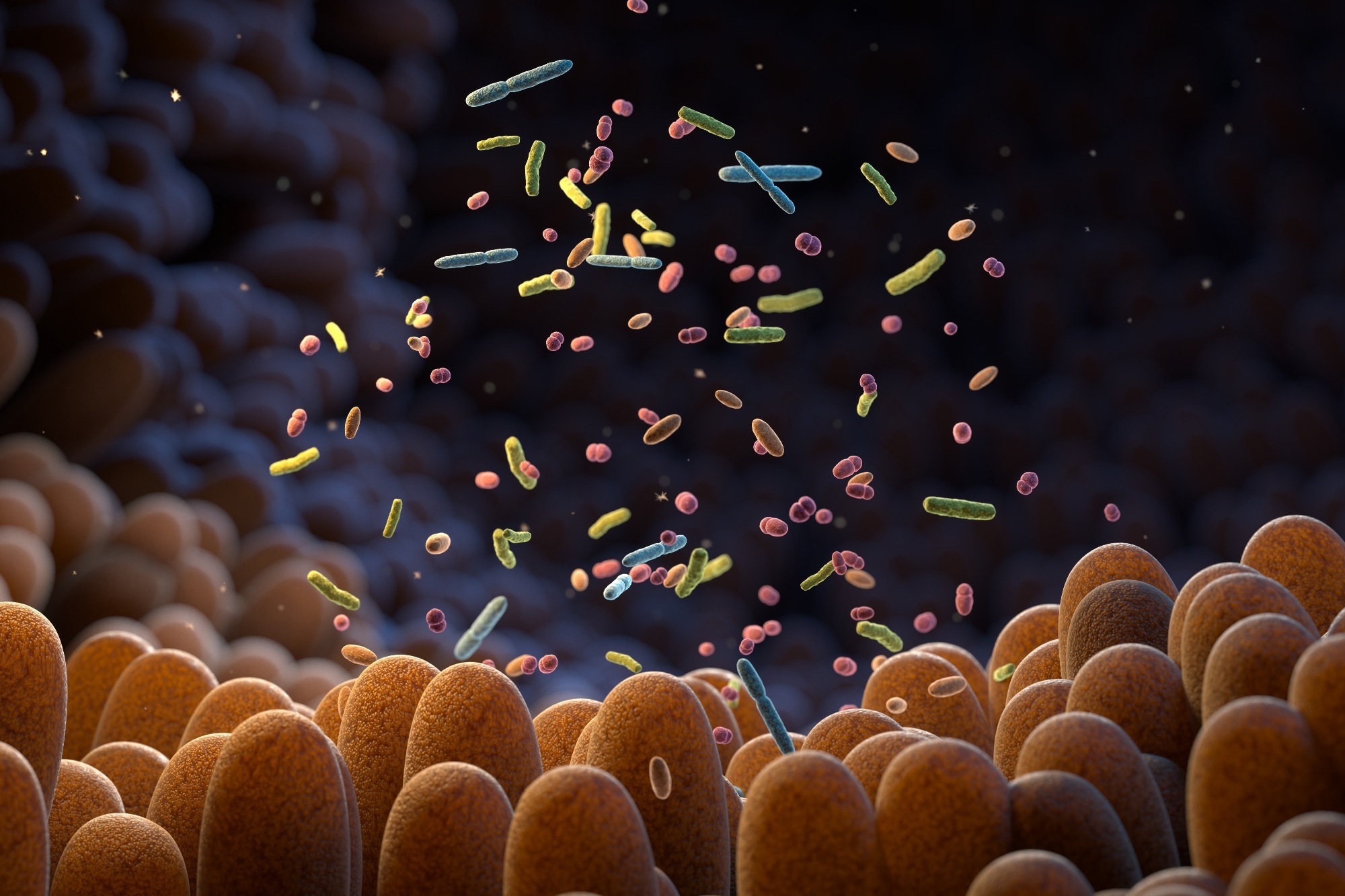

Study: Diversity in women and their vaginal microbiota. Image Credit: Tatiana Shepeleva/Shutterstock.com

Study: Diversity in women and their vaginal microbiota. Image Credit: Tatiana Shepeleva/Shutterstock.com

A recent study published in Trends in Microbiology discussed the diversity in females and their vaginal microbiota.

Background

Females and knowledge about their health have been controlled, persecuted, and neglected for centuries, leading to health disparities that still linger. Western medicine assumes an androcentric perspective at the expense of females.

While females have a higher average age, older females are more frail than age-matched males. This is associated with severe social and economic costs.

Reproductive tract-related conditions are among the most pressing health issues for females; many of these conditions are linked to the vaginal microbiota, which comprises bacteria, fungi, viruses, and archaea.

The composition of vaginal bacteria in healthy individuals has been classified into community state types (CSTs). However, the CST classification does not capture the complete function and biology of the vaginal microbiome.

Regardless of the approach to classifying vaginal microbiota, studies have reported associations between vaginal microbiota and different clinical conditions.

Reductions in lactobacilli are associated with pregnancy complications, such as preterm birth, endometritis, urinary tract infections, and sexually transmitted infections.

Bacterial vaginosis is not a disease but is related to disease

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a condition of non-optimal vaginal microbiota and is characterized by an overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria and a decrease in lactobacilli. The term BV is under reconsideration as not all females with BV have symptoms.

As such, it is essential to underscore that BV is not a disease, and it must be assessed in the right context. BV is usually diagnosed based on the Amsel criteria or Nugent score.

The Nugent score is based on Gram staining, which makes it possible for females to be BV-positive even if no symptoms are present.

Conversely, the Amsel criteria might be more appropriate as they are based on vaginal fluid pH, presence of clue cells, abnormal vaginal discharge, and positive whiff test, and at least three signs must be positive for a BV diagnosis.

Standard BV treatment includes clindamycin or metronidazole, which has about 60% recurrent rate, indicating a lack of a sustained response. As such, a novel therapeutic approach for BV-related symptoms and diseases could involve direct modulation of the vaginal microbiome, such as vaginal live biotherapeutic products and vaginal microbiota transfer.

Global disparities in vaginal microbiome research

Studies suggest that an increase in BV and lack of lactobacilli are more often observed in Latin American and Black females than Europeans or Asians in the United States (US). However, these studies generally lack information on participants’ geographical history, dietary and cultural lifestyle, birth country, and socioeconomic status, which might confound these associations.

Moreover, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are generally under-represented in all microbiome studies. Also, it is challenging to increase diversity in vaginal microbiome research as prevailing research infrastructure and financial capacities are skewed towards high-income countries.

Sample collection, metadata acquisition, and microbiome analyses also require trained personnel and data processing.

LMIC researchers should forge international collaborations to overcome these material challenges, and adherence to the principles of collective benefit, authority to control, responsibility, and ethics (CARE) should be ensured to prevent an imbalanced relationship.

Initiatives to increase representation and challenges that remain

Various initiatives have been introduced to close the gap in vaginal microbiome data across the world. For instance, the vaginal human microbiome project maps vaginal microbiota data from persons of different ethnic backgrounds in the US.

In addition, the VIRGO database comprises data from countries across Asia, America, Africa, Oceania, and Europe. The diversification and globalization of vaginal microbiome research faces several challenges.

The terms ethnicity and race have been widely used in vaginal microbiome studies to report microbiological differences. However, the history of ethnicities and race is linked to political and social struggles for domination, shaping health and social inequalities for centuries.

Racial categories are more socially constructed than based on biological differences. While gathering data from diverse populations is crucial, it should be adequately considered.

Concluding remarks

In sum, more research on the diversity and functions of the vaginal microbiota is urgently required across the world to promote better diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive strategies for females affected by vaginal microbiota-related conditions.

Besides, the continued portrayal of lactobacilli as a standard for optimal vaginal health requires re-evaluation with unbiased global diversity perspectives.

Moreover, equitable and fair capacity building and collaborations are also essential to increase diversity in vaginal microbiome research.