As a society, we may be more obsessed with food than we've ever been. The alarming levels of obesity along with the rise of clean eating and orthorexia are perhaps just some indicators of the food-obsessed world we live in.

There is a multitude of information out there on food and diet but also a lot of smoke and mirrors. A recent Royal Society of Medicine event 'Food: The good, the bad and the ugly' aimed to bust some of the myths around nutrition.

Firstly, Professor Ron Maughan, University of St Andrews, discussed the role of nutrition for elite athletes. While he clearly stated there is an immediate link between what you eat and how you perform, he also recognized that nutrition isn't enough to make a good athlete. Quoting ex-football manager Harry Redknapp:

If you can't pass the ball properly, a bowl of pasta’s not going to make that much difference!"

Maughan outlined how sports nutrition needs to be tailored to individual needs and varies significantly by the type of activity. For example, a gymnast that trains 4-6 hours a day may not necessarily have very high energy demands as their training maybe about technique rather than intensity.

Athletes are creatures of habit, often training and also eating in regimented ways. It is difficult, however, to give specific answers to questions such as 'How much energy intake is enough?' 'How much fat is too much?' As it depends on many different factors including growth needs, individual characteristics, body fat, muscle mass and of course how much, and also the type of, training the athlete is doing.

Supplements are very popular amongst athletes. Prof. Maughan quoted a survey of 310 athletes competing in IAAF World Championships, where almost 90% stated they were using some form of dietary supplement. The cost versus benefits were highlighted by Prof Maughan including the dangers of contamination and the problem this can cause athletes with failed drug tests.

Following the discussion of elite athletes, the conference then turned its focus to the general population, with Professor Rachel Batterham, University College London Hospitals, sharing some staggering statistics including the global number of obese people: over 600 million. This is having an impact on overall life expectancy particularly in the US where this is actually declining. Also shockingly, 1 person dies every 6 seconds from Type 2 diabetes.

Prevention is much better than the cure, but with two thirds of the adult population overweight and 25% obese, we also need to seek treatments for those already affected. Firstly, Prof Batterham talked about the problems with people's perceptions of their own weight with many not realizing that they are overweight. Batterham called on healthcare professionals to do more to raise this subject, suggesting to ask permission to talk about this in consultations with patients who are carrying excess weight.

Batterham also went on to discuss the gut hormones, such as ghrelin and peptide YY (PYY), that play a large role in our feelings of hunger and food intake, along with genetic factors such as the fat mass and obesity-associated gene (FTO). Batterham gave a fascinating insight into what happens to our biology when we diet and explained why it is so difficult to keep weight off once we have lost it as dieting negatively impacts our biology so that you end up with increased hunger and increased interest in food even a year after you've been on a diet.

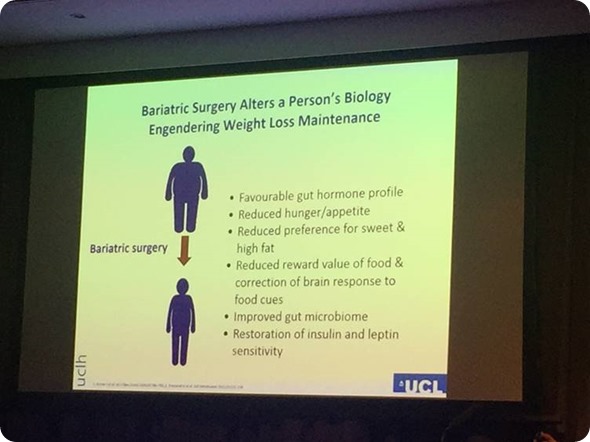

In contrast, Batterham outlined the metabolic changes that occur following bariatric surgery such as gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy, which she claimed don't work through restriction but through changes in gut hormones meaning that the patients no longer feel hungry. NICE in the UK are now recommending that anyone with a BMI of 35 or over who have recent-onset type 2 diabetes should be assessed for bariatric surgery. The ultimate goal though is to be able to induce these metabolic changes without surgery by reprogramming our gut cells.

Using food and the power of the microbiome was a big theme throughout Dr Charlie Lees' talk. Lees outlined the evolution of humans and how our diet has changed drastically from our common ancestor with chimpanzees 7 million years ago, through the early phases of bipedal humans, the hunter gatherer phase, the agricultural revolution and the industrial revolution.

The rise of inflammatory bowel disease - Crohn's and ulcerative colitis - from the early 20th century to the current incidence of 1 in 200 people is another area Lees focused on. His patients frequently ask him what they can do to help their condition, what foods they should be eating and so forth but unfortunately the answer is we still do not know.

This is an area of much research, however, with studies on microbial diversity, fibre intake, high fat diets, and emulsifiers. The challenge in such research is identifying cause or effect as the research is frequently carried out with populations who already have IBD. Lees is conducting a study called GEM that aims to overcome this challenge by studying healthy 1st degree relatives of patients with Crohn's disease to compare those that do get Crohn's to those that don't. Hopefully this will help to elucidate what causes disease flare ups and in a few years we may be able to give some answers to patients.

Dr Liam O'Mahony outlined the importance of the microbiome and also the short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) our microbiota produce, which have an important role in immune regulation. Professor Tim Spector, King's College London, also raised the subject of microbial diversity and how there is huge variation the gut microbes from person to person, with us only sharing around 20% of microbes with each other.

But short of a fecal microbiota transplant what can we do to improve our gut microbial diversity? Prof Spector discussed how hunter gatherer tribes in Tanzania live off the land and consume an average of 600 species per year, whereas the average British person eats just 50. The more diverse the species you eat, the more diverse the gut bacteria. Spector encouraged us to treat our guts like a garden, by using regular fertilizers, such as probiotics to feed our gut bacteria, along with experimenting with eating different foods and avoiding antibiotics and pesticides.

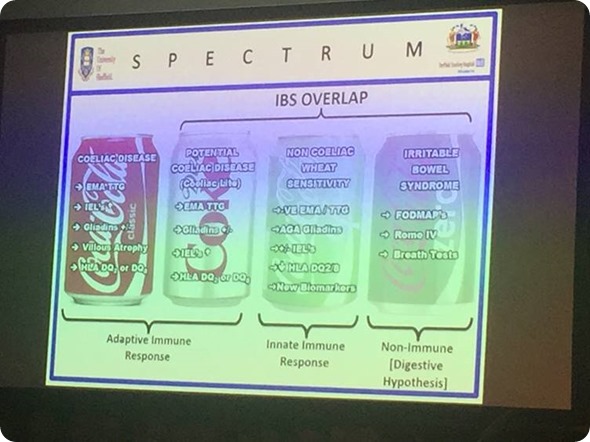

For some, such as those with IBS, it can be challenge finding the right diet due to the overreaction to certain foods. Nick Trott, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, provided us with a thought-provoking cola can metaphor of the spectrum of gluten and wheat sensitivity some of which crosses over with IBS.

Trott made it clear that diets such as gluten-free and low FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols) in IBS and non-celiac gluten and wheat sensitivity should only be a temporary measure and it is essential to have the right support. Registered Associate Nutritionist, Rhiannon Lambert, Harley Street Private Clinic, discussed the rising trend of self-diagnosis and the dangers of unqualified advice.

The wellness revolution and clean eating promoted by some celebrities and influencers is impacting the rise of orthorexia. Whilst there is no official definition and the condition isn't currently recognized as an eating disorder in DSM-5, Lambert outlined three key questions defining orthorexia:

- Is diet and exercise taking up an inordinate amount of attention?

- Is deviating from that diet met with guilt and self-loathing?

- Is diet used to avoid life issues and leaving you separate and alone?

And so whilst it is clear that food plays an important role in our nutrition, microbiota and thereby our health, it is a fine balance between eating good foods, avoiding too many bad ones and maintaining sufficient diversity without restrictions leading to orthorexia.