Researchers have found that infusing elderly mice with human umbilical cord blood boosts the animals’ learning and memory capabilities.

The team, from Stanford University School of Medicine, also identified a single protein in the blood that seemed to be responsible for the improved cognitive performance.

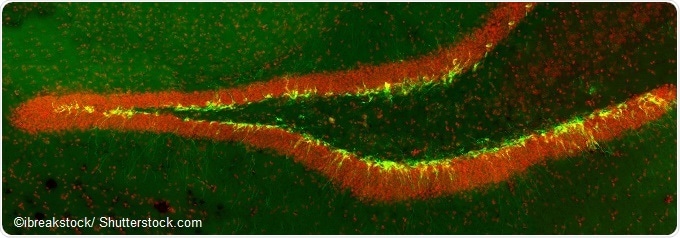

New born neurons in the transgenic mouse hippocampus (dentate gyrus) labeled with green fluorescent marker. Implicated in mood and memory.

Senior author of the study Tony Wyss-Coray says: “To me it’s remarkable that something in your blood can influence the way you think.” From a drug-development standpoint, it is also promising “that a single protein appears largely capable of mimicking those benefits,” he adds.

The protein is abundant in human umbilical cord blood, but becomes less abundant in blood as people age. When the mice received the umbilical blood every fourth day for two weeks, their measures of hippocampal function improved considerably. On the other hand, blood from older individuals had no effect at all, while young adult blood had an intermediate effect.

The hippocampus is a brain region that converts experiences into long-term memories and plays a particularly important role in spatial memory, which helps a person remember information such as where they parked their car in a multi-storey car park or what they ate for breakfast.

To investigate further, the team compared 66 proteins they identified in the umbilical cord blood with proteins found in older people’s blood and those identified in the mice. After finding several potential candidates, the animal were injected with the proteins, one by one, and then put through memory tests.

As reported in Nature, only one protein called TIMP2 (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteases 2) improved the animals’ performance. Even their ability to use materials to build nests was restored, something that is largely lost in elderly mice. Injecting the mice with blood that lacked the protein, on the other hand, had no effect on their performance at all.

Wyss-Coray and lead author Joseph Castellano say they don’t yet understand how the protein influences the brain, but finding this out is the next priority. The researchers are particularly interested in whether the effect is specific to ageing or general to cell health.

Neuroscientist from the University of Kentucky, Philip Landfield, says: “It’s a bit of a black box experiment, because they don’t know what's happening.” However, the most promising aspect is the potential to translate this into a therapy, he concludes.